Presented by New York Passive House and Passive House Accelerator, the Urban Passive House Series explores Passive House solutions and lessons-learned for urban settings, drawing on built examples from major metropolises across North America. Episode 2 features Cooper Park Commons, a multi-building development on the former Greenpoint Hospital site in the East Williamsburg neighborhood of Brooklyn. It will offer nearly 500 units of affordable housing, 110 units of senior affordable housing, a 200-bed homeless shelter, a health clinic operated by NYU Langone, retail and community facility space, and public open space.

With associated architect AO, the first phase of MAP’s work begins with Building #2. This 18-story, 311-unit affordable family housing will achieve Passive House certification and offer amenities including a lounge/workspace, exercise room, package room, playroom, laundry room, community rooms, landscaped courtyard, and landscaped terrace. Sara Bayer, Associate Principal and Director of Sustainability at Magnusson Architecture and Planning (MAP), shares the design strategy behind this groundbreaking project. Watch the video here.

Note: This episode was rerecorded due to a technical issue

Related Videos

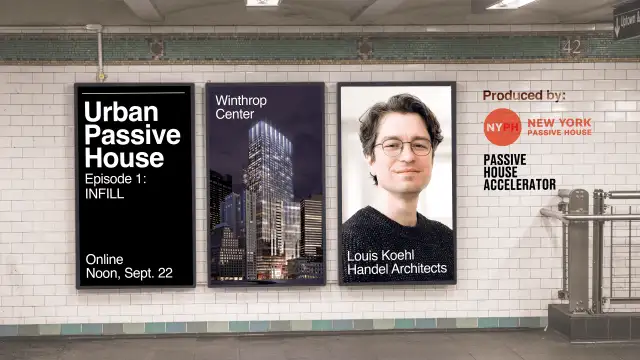

9/22/22

Urban Passive House, Episode 1: INFILL

Video, Commercial, Institutional, & Other, Urban Passive House Series

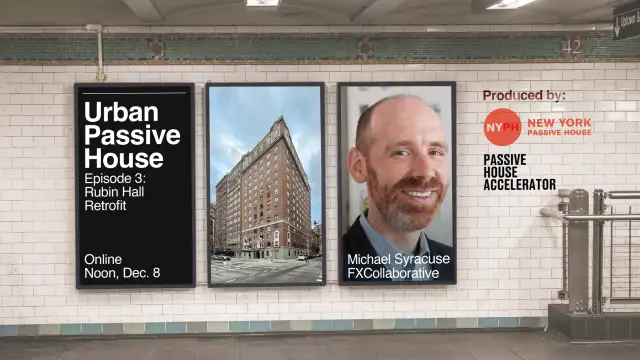

12/8/22

Urban Passive House, Episode 3: Rubin Hall Retrofit

Video, Retrofit, Urban Passive House Series, Climate Action

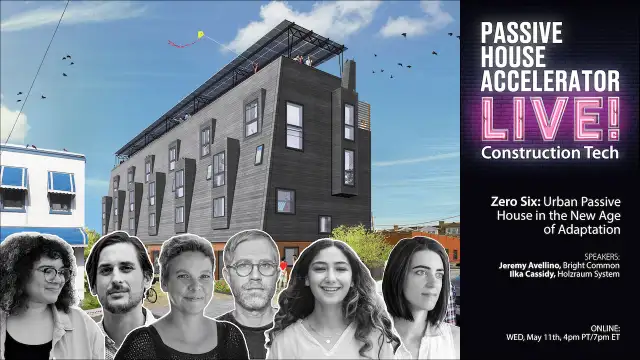

5/11/22

Zero Six: Urban Passive House in the New Age of Adaptation

Video, PHA Live