[Editor’s Note: This article was originally published as part of the 2019 NAPHN Policy Resource Guide, release at its 2019 conference. Registration for this year’s NAPHN conference, PASSIVE HOUSE 2020, opens March 2.]

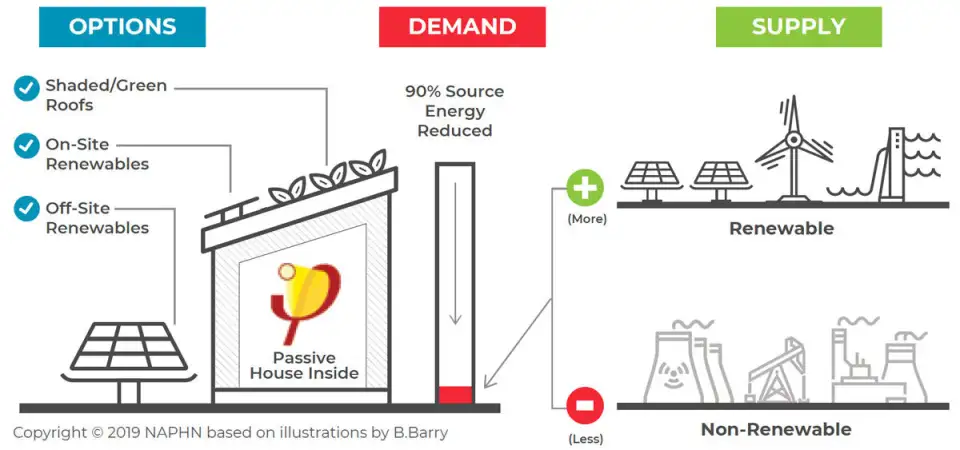

In a big, bold move the City of Vancouver set a goal of running only on renewable energy by 2050. In order to do that the city needs to greatly reduce its energy use first—from all sectors.

Identify the Leaders

As one step toward accomplishing that reduction in the building sector, in 2008 the City of Vancouver started to allow Passive House as an alternative compliance path to its rezoning policy for larger buildings. When a leading developer proposed using Passive House to meet their rezoning requirements, the City staff gained valuable experience from working with that project, and also other projects, and recognized the barriers—and then worked to remove those barriers—to achieving Passive House on individual projects.

City staff were motivated to assist with Passive House implementation because they had been seeing newly constructed LEED-certified buildings that were not achieving energy use or greenhouse gas reductions. LEED certification drew on ASHRAE 90.1, which used energy cost to calculate savings. That drove new buildings toward cheaper gas and away from electricity use, resulting in higher total greenhouse gases from space heating—an increase that was also propelled by these building envelopes often being thermally weak. The buildings that were performing the best were actually small buildings that only had to meet a prescriptive insulation requirement [Vancouver has its own building by-law (code)] and therefore had a better thermal envelope. It was clear that improved thermal envelopes were needed citywide to achieve lower greenhouse gases and reasonable operating costs.

Set Higher Targets

We have seen market economies excel at responding to demand with products. Passive House has certainly proved this rule. With more new buildings pursuing Passive House, demand for high-performance products and for high-performance buildings generally has increased—and the Passive House buildings that have been built are demonstrating the many benefits of this approach. This shift towards incentivizing Passive House has allowed Vancouver to improve the base building code. In 2016 the Vancouver City Council adopted the Zero Emissions New Building Plan, which clearly articulates the path that new buildings must take and outlines the lessons from Passive House (better envelopes, lower heating energy, less use of fossil fuels). This plan proposed that Council direct staff to execute a better building code and a better rezoning policy for larger buildings.

Support Front-Runners

The City understood that more Passive House projects would be needed to serve as the icebreakers, making way for all buildings to move toward high-performance outcomes. To smooth their paths, we focused on removing barriers to Passive House, starting with single-family homes, which we allowed to be taller. We also allowed them to cover more of the lot, and we ensured that the thicker walls did not mean less living space.

Educate Everyone

Once early barriers to Passive House had been removed, we then focused on training staff. Over 100 city staffers received Passive House training, including a number of planners and two in-house trades-certified inspectors. This greatly increased the chance that a Passive House project team would get to work with City staff that would understand what the project was trying to achieve. We then funded a 50% trades training subsidy to support local industry adoption.

Remove the Barriers and Increase Incentives

These barrier removals and trainings have made it easier for every project. We then moved on to barrier removal for all buildings, putting in place a 2% floor area exclusion for any Passive House using an HRV that was PHI-certified and commissioned in the field. A more recent policy has been the addition of a 5% floor area bonus for any multifamily building that includes five or more dwellings. This took a significant amount of time to be approved. Council wanted staff to ensure barriers were removed and training was done first as these were seen as foundational level pieces. For ground-oriented projects we also launched http://nearzero.ca/, which is a case study program that provides up to $20,000 to any new zero emissions buildings. Most of these have been proposed as Passive House.

Striving for Real Change

U.S. economist, Milton Friedman said: “Only a crisis—actual or perceived—produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around.” We are now at a point where we need these great ideas that are lying around—like Passive House. I have now worked at the City of Vancouver for five years and most fellow civil servants I have met come to work for the city to make Vancouver a better place. Many also strive to make Vancouver an example of what is possible on the global stage. We now have Passive House buildings that are 50+ story high rises, single-family homes, fire halls and childcare facilities, along with everything in between. We now have the ability to show what is possible with Passive House and how this approach can help us achieve our climate, energy, and resiliency goals.

We are a city with our share of challenges—housing affordability, homelessness, and an over-dose crisis just to mention a few—but we are also a city that is working to tackle global problems with scalable solutions. We borrow the biggest, boldest ideas from around the world, and when I looked at Passive House I could see it was a well thought out and well executed “big bold idea” for buildings. Local leaders helped by designing the first few Passive House projects, proving this approach is realistic. Those projects blazed the trail for the City to step in, remove barriers, get trained up, and put in place incentives to build market interest.

Six Big Moves Aimed at One Goal

City staff was recently directed to work on a Climate Emergency Report that gained unanimous support. This report includes six big moves. For buildings, the move is toward no more fossil-fu-el use for space heating or hot water after 2025. Staff are working on a building code update to deliver this sooner for new buildings. Another big move is aiming for a 40% reduction in embodied energy in new buildings. The work is focused, and staff work with urgency to achieve one overarching goal—the decarbonization of our built environment.

(Vancouver skyline photo courtesy of Patricia Keith.)