In 2016 I received a call from a new client, John, who had a dream to build a house. I immediately got the sense that he had a great analytical mind, as John spoke about his research into LEED and his ultimate decision, after further consideration, that his home must be a Passive House. He very much liked our Mamaroneck Passive House, and so we scheduled to meet in person. We immediately clicked and started the journey to realize his Passive House dream on a beautiful lot adjacent to a private pond in the heart of Scarsdale.

John had bought the property in the ’80s, because it was only a short distance to the train station, allowing him to travel in just 35 minutes to New York City, where he worked as a lawyer. He had lived for decades in the small, original house that had been built in the ’50s. However, it had moisture problems in the basement because of the slope in the back and the rock formation it was built on. It became clear that the best path forward would be to demolish the existing home and make room for a new house.

The new home John envisioned had to be clean and modern, with almost a Scandinavian feel. I immediately thought the building must be connected to the backyard with its gigantic trees and the beautiful pond that it faces. The pond is the center of the Crane Berkley historic neighborhood. Before seeking a permit from the Scarsdale Architectural Review Board (ARB), we documented more than 100 buildings in the neighborhood, seeking inspiration for a Passive House that would blend in harmoniously as required by ARB design standards. Unfortunately, the first ARB meeting did not go well; the design was too modern and the triangle window at the top of the gable was considered an affront.

We had to go back to the drawing board. I redesigned the window layout and switched the façade from a horizontal siding to brick, which turned out to pose new challenges but enhanced the design and curb appeal. From that point on, the approval process went much more smoothly, and we even started the second ARB meeting with an introduction to the Passive House concept. We won them over, even gaining consent to omit the highly recommended window mullions because of the thermal bridging issue they would have created.

John wanted a house for himself. Our planning and design discussions could be free of any thoughts related to marketability, because he had no interest in selling it ever. What did interest him were innovation, new technologies, and a connection to nature; he is a world-traveling bird-watcher. A beautifully planned and executed natural landscaping firmly plants the home in its surroundings.

We designed the building as a split level because of the sloping terrain and connected all levels of the house with a central residential elevator. The first floor is an open living space with an integrated modern kitchen, which John described to me as a laboratory for food preparation rather than a traditional kitchen. A large music room was designed over the garage to accommodate John‘s harpsichord. The master suite and a guest bedroom and bathroom are separately located on the second floor, each with its own outdoor terrace. The cellar was included in the building envelope and offers a large space to accommodate a gym for daily exercise.

Construction initially went slowly, as we had to chip away at a rock formation to make room for the new cellar and spread footing. Because of the high water table, we decided to insulate the foundation walls from the inside with a French drain on both sides of the footing. Below the cellar floor system, we installed gravel with a radon mitigation system and a 15-mil membrane as the airtight layer and vapor barrier. A highly reflective radiant shield was placed over the membrane to increase the efficiency of the floor heating. This membrane folds up and is connected to the membrane covering the foundation walls. We placed 6 inches of high-density EPS under the membrane. The 4‑inch reinforced concrete slab has hydronic floor-heating PEX tubing embedded in it. A major consideration was finding a low-VOC flooring material for the cellar, one that was thermally stable and moisture resistant but vapor permeable. We eventually chose a natural ½‑inch cork flooring from Canada.

The entire building is framed with 2 x 6s. We lined them up with the sill plate on the interior of the foundation walls so that the brick façade could rest directly on the foundation with weep holes to the exterior. It was decided to use a self-adhering membrane as an airtight layer and a weather-resistive barrier (WRB) over the structural plywood sheathing. We placed a 3‑inch layer of comfort board over the WRB and a separate 6‑inch layer in the back, where we used horizontal cement board siding. Thermally broken brick ties connect the brick to the structural frame wall. The required expansion joints were integrated at the recessed brick corners and disappear from the eye of the observer. The interior framed 2 x 6 wall cavity is filled with dense-packed cellulose insulation and is used as a service cavity for all electrical wire installations.

Windows are a very important decision, both because of their complex requirements—U‑value and solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC) specifications—and because of how they impact the whole project’s sequencing and overall aesthetics. My experience tells me to have the window discussion with clients early on. I organized a showroom visit to allow John to appreciate the complexity of the window decision. We decided to use a window with a PVC core, solid wood finish on the inside, and aluminum cladding on the exterior. I specified windows with a higher SHGC for the home’s south side to maximize solar heat gain in the wintertime. In the summertime, big deciduous trees provide protection from the steep summer sun.

The windows were installed with a drainage system integrated into the window trim to guide any runoff water to the exterior of the siding. The window screens were integrated into the trim by routing out a channel at the edge of the trim, allowing them to almost disappear into the groove of the frame. This approach turned out to be a very good solution, because the screens can be changed and maintained easily.

John wanted radiant floor heating in the cellar, which turned out to be a pretty good idea. To allow for an even heat transfer to the next floor, I designed the cellar and first-floor plans to be the same. This strategy minimizes the problem of stratification between the different floors and is a good way to maintain thermal comfort throughout the house. Last winter, John’s experience with this heating system was very positive, and he particularly appreciated that it evenly heats the entire house from the bottom up. A radiant floor heating system had been installed in all the bathrooms as well, but that turned out to be a redundant measure; the bathroom floor heating never turned on last winter.

Hot water for the radiant floor heating system and for the domestic hot water is delivered from a direct-vent condensing boiler, which is so small it hangs on the wall. I had initially suggested a heat pump water heater, but the instantaneous and almost silent nature of the tankless water heater won the day. The gas connection was installed just before the gas moratorium in Westchester County went into effect. The building would be easy to convert to all-electric, because we designed a hybrid heating system.

The primary heating-and-cooling system is a hyper heat mini-split. One compressor serves two air handlers on the north side of the building. Both air handlers have ducted distribution systems. The first air handler is located in the suspended ceiling of the first floor, serving the cellar and the first floor. The second air handler is located in the attic and serves the second floor. A second outdoor condenser was installed on the south side of the building to serve a wall-mounted indoor unit in the garage and a ceiling-mounted indoor unit in the music room, which is located over the garage and is exposed to the outdoors on three sides. Last winter’s heating strategy was to keep the radiant floor at about 72°F and maintain the air handlers’ setting at 70°F to minimize the use of the mini-split system.

After the attic floor was framed, we transitioned the airtight and vapor permeable WRB layer of the exterior walls to the edge of the attic floor and on up to the interior side of the roof rafters. Then, we taped the attic floor airtight layer to the air barrier and smart vapor control membrane on the interior side of the roof rafters. This approach allowed us to frame the roof rafter overhang in a traditional way and avoided the need to add an overhang at a later point. We used a 10-inch high-density batt insulation between the 2 x 12 rafters. This created a 1‑inch ventilating channel between the outside sheathing and insulation. We then framed an interior 2 x 4 layer along the roof rafters with a 2‑inch gap to avoid thermal bridging along the rafters. This layer was filled with dense-packed cellulose insulation and serves as an installation cavity for the electric wires and light fixtures. The attic floor maintains a very even temperature throughout the year, since it is included in the building envelope. In order to create the needed 10-inch overhang of the gable front wall over the brick façade, we decided to reverse the attic floor framing perpendicular to the front wall. This framing strategy turned out to be very successful and is most likely something our office will specify for other projects in the future.

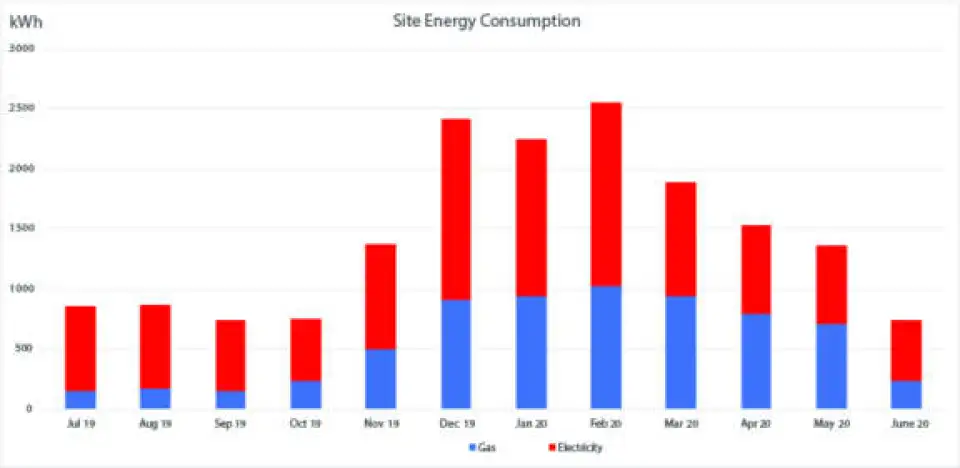

John has lived in the building now for more than a year and from time to time calls me up on a very hot summer day or after a cold winter storm to let me know how well the building is withstanding the extreme weather conditions without much of an energy increase. So far, based on an analysis of the bills from Con Edison for the last year, the building is performing as modeled with the PHPP. When Con Edison came to read the gas meter for the first time last winter, the meter reader assumed the meter was broken, since it showed such a low gas consumption for such a large home. So the utility didn’t use its own meter reading, and instead used the average gas consumption for a comparable home in the area. John called and pointed out the invoice mistake and insisted that a Con Ed technician come back to confirm the initial reading. Of course, the next month the invoice showed up with the same mistake, reflecting a continued disbelief in its own gas meter reading. It took until the third month for Con Edison to finally accept how low the energy consumption of our Scarsdale Passive House really is.