The city of Northampton, Massachusetts, is perhaps best known for being an academic hub. It is home to Smith College, one of the most respected liberal arts institutions in the country, and within just a few miles of four additional schools that make up the Five College Consortium.

Of course, Northampton is more than just a magnet for students. It is also home to many artists, artisans, and musicians, who contribute to a vibrant arts scene and a picturesque Main Street.

For David Fox, founder and CEO of Live Give Play, the combination of cultural amenities, proximity to academic institutions, and walkability made Northampton an ideal location for a new, 110,000-ft2 development designed to give people over the age of fifty-five the opportunity to connect with the community in a more dynamic and meaningful way. Named after its address, 79 King Street, the 70-unit project will include studio, one-, two-, and three-bedroom apartments and is expected to break ground in 2023. It is planned to be completed 16 months later.

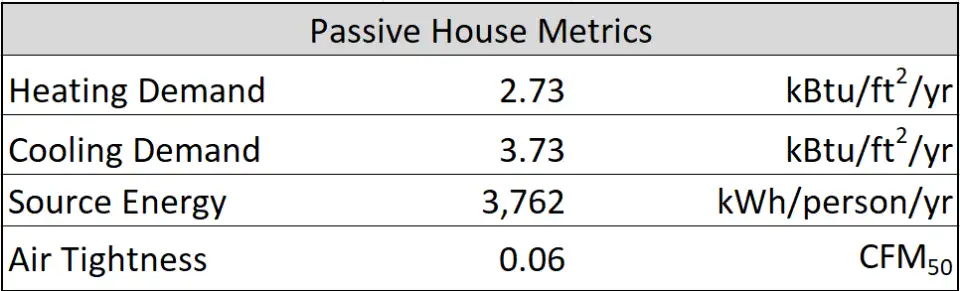

It should be stressed that 79 King Street is not a retirement home, but rather a multifamily building for older people that promotes healthy lifestyles while strongly encouraging civic service and engaging with the culture of the area—live, give, play. As the project will be seeking PHIUS+ 2018 certification, built using mass timber, and all-electric, it will be an exemplar of sustainable construction, as well.

Live Give Play

Fox says he has always been fascinated by the housing industry, but the first 40 years of his career were in film and television. It wasn’t until roughly a decade ago, as the industry accelerated its rapid evolution from analog to digital, that he decided to change careers and began working in real estate development.

Film and television were not the only industries evolving at the time. A combination of new technologies and the lingering effects of the Great Recession had resulted in seismic shifts within virtually all professions, and many people from Fox’s generation were not only being let go from their positions but were also struggling to find new ones. Many baby boomers who had attained solid middle class status and long ago moved into large suburban homes have been facing financial difficulties. And, their homes have become increasingly a burden as their associated expenses—be it property taxes, maintenance and repairs, or utility bills to heat and cool them—mount.

Fox believes that this is an unsustainable scenario that can be rectified by leaving the single-family home behind and moving back to cities. “If they can sell their house, move into a walkable neighborhood, and not necessarily need one car per person, then they're well on their way to saving money,” he says. “And more importantly, in an urban infill situation, they would be amongst other people.”

In addition to providing opportunities to be active and social, Fox says urban areas like Northampton will benefit from older residents from the Live Give Play community who can work with institutions to pass down wisdom and experience to the next generation. This transfer of knowledge need not be limited to colleges and universities. Fox notes that the local Chamber of Commerce can also facilitate mentorships to benefit local businesspeople who lacked the resources to go to business school. Ultimately, these kinds of commitments not only enrich the lives of younger individuals; they also give future King Street residents a sense of purpose and the opportunity for civic engagement.

Given that 79 King Street is at the edge of Northampton’s downtown and within half of a mile of Smith College, residents will be able to easily walk to either Main Street or the campus. Fox is also promoting the use of bicycles over cars. The property will be equipped with a shed for bike storage, a bike repair area, and most of the 3,500 ft2 of the building’s ground floor will be bicycle-oriented retail. Residents will be able to easily access several bike trails, including one that connects Northampton with six other cities. Eventually, these trails will connect to a network that stretches all the way to New Haven and North Station in Boston. For those who do need a car, but do not want the burden of ownership, Fox says there will be a shared electric car program onsite that residents can lease by the hour or day.

Unfortunately, Fox felt that his work in real estate finance hadn’t fully prepared him to tackle such a lofty project without assistance. As he joked with his partners, “I wouldn't invest my own money in me if I were the only one doing the development.” His two partners, Nancy Kleppel and Patrick McDarrah, similarly have some experience within the world of real estate but recognized that such an ambitious project would require someone with more expertise.

Enter developer Jeff Spiritos, principal of Spiritos Properties LLC.

By partnering with Spiritos, the team gained decades of experience working on ground-up development projects in the Northeast. Moreover, Spiritos has been working on projects that utilize mass timber construction since at least 2012 and has been a vocal proponent of Passive House design since being introduced to the standard by Stas Zakrzewski of ZH Architects almost a decade ago. He believes that working with both mass timber and Passive House design is a way to address both sides of the carbon equation; the former addresses embodied carbon, while the latter addresses operational carbon. “That's the way I believe people should be building buildings,” he says.

According to Fox, Passive House also figured into the equation because of the incentives offered through the state program Mass Save, which offers developers who obtain Passive House certification a $3,000 subsidy per unit. “We figured, if the state is that behind it, and we can get that subsidy even if it costs us more, look at how much energy we're saving for our tenants and ourselves,” Fox says. “It's the right thing to do.”

Fox felt the same way about using mass timber to cut embodied carbon. “We feel that it's kind of a now-or-never time in the building trade,” he says. “If we don't take into consideration the environment and use all possible means to eliminate or mitigate carbon, then shame on us.”

79 King: Head and Tail

Spiritos believes that Northampton is a “development positive town”, but stresses that residents also want to ensure that everything that gets built downtown fits its established aesthetic character. “They've got guidelines in zoning that are supportive, and they want buildings that are respectful of Northampton’s history, but also progressive,” he says.

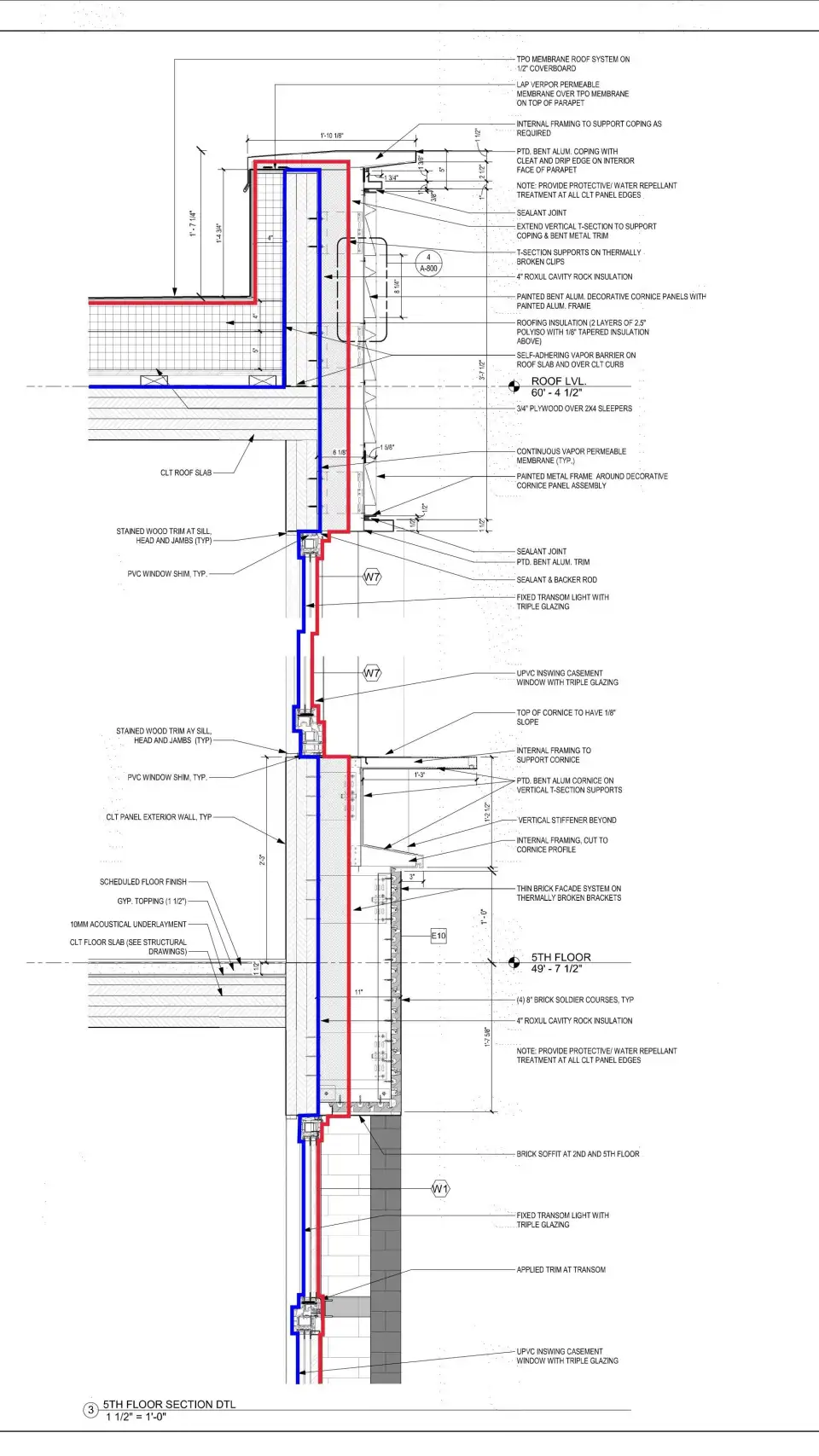

To preserve downtown’s historic character, developers are required to go before Northampton’s Architecture Review Board, submit a plan, and get their approval before being issued permits. Plans must adhere to a design guide that, according to David Kubik, partner at the New York City-based BKSK Architects and the architect for the project, is very specific and can sometimes be somewhat tricky to navigate. This is especially the case when building performance takes such a high priority.

One of the guidelines that posed a significant design challenge for the team was the restriction on grilles or louvers on street-facing facades. Kubik explains, “When doing a Passive House building, it’s really helpful if you can have the ERV [energy recovery ventilator] intake and exhaust directly at the unit and to have some small grilles populate your façade.”

As this wasn’t possible on the side of the building facing the street, the team decided to split the one-over-four building into two four-story towers atop a shared podium. For the street-facing side, which Kubik refers to as “the head building”, the team developed a more centralized system for the heating, cooling, and ventilation where everything is brought up to the roof. For the side that does not face the street, “the tail building”, Kubik says that a centralized system will be used in the hallways and public spaces, while each apartment will be outfitted with a unit manufactured by Ephoca that will provide ventilation, heating, and cooling. As there are no design restrictions on façade penetrations for this side of the building, each system’s ductwork, including intake and exhaust openings, can be localized entirely within the unit.

The cladding systems for the head and tail buildings will be notably different, as well. The tail façade will consist of cement-board cladding supported by a wood batten system. The façade of the street-facing head building, however, must comply with design guidelines for the city and replicate the historic masonry seen elsewhere throughout downtown. To capture this aesthetic, the team will rely on the Corium brick cladding system manufactured by Interra.

According to the project’s Passive House consultant, Michael Hindle, principal of Passive to Positive, the roof assemblies for both the head and the tail buildings will each have R-values of 53 and include 7 inches of cross-laminated timber (CLT) slab material and another 7 inches of polyiso. Hindle hopes the polyiso can be reclaimed from another project.

In addition to being home to mechanicals from the centralized ERV system, as well as a Sanden heat pump water heater system that will service the entire building, approximately half of the 20,000-square-foot roof will contain a PV array that is expected to generate 121.2 MWh annually. The other half of the roof space will include amenities like benches, tables, and small herb or vegetable gardens for residents.

Materials Matter

Though there are significant differences in the mechanical and cladding systems, the bones of the two sections of the building will be constructed using similar materials. Both will consist of glulam columns and beams—engineered laminated wood beams—with CLT floors and exterior wall panels. “When you’re in your final apartment, other than some drop ceilings over kitchens and bathrooms, you’re going to be looking at the underside of the wood CLT panels, as well as the exterior,” Kubik says. “It has a real effect on what you experience when you’re in that apartment.”

The wall assemblies between the CLT panels and cladding will also be similar. The air and water barrier will go directly on the outside face of the CLT wall panels, and then be followed by 4 inches of either mineral wool or wood fiber insulation. According to the most recent model, the head and tail walls will have R-values of 23.

Assuming that the podium is made of concrete, the walls on the ground floor will be R-19. However, the team is considering using mass timber in its place. This would not be a first for Massachusetts or even for Hindle, who is finishing work on a project known as 11 East Lennox, a seven-story building that is the first ground-up mass timber structure in Boston.

The team is cutting down on embodied carbon by using wood studs instead of steel ones and hope they can complete the project with minimal use of plastics or foam. Furthermore, Hindle notes that preliminary modeling suggests that switching to only wood fiber insulation in the envelope of the building will take the building into carbon negative territory and could offset up to six years of operational energy.

Life on King Street

“This project has been really special and exciting,” Hindle says. “Jeff and David have been terrific. Talking about it just by the data does not do it justice. There is a real ethic behind it, and they welcome input and advocacy around environmental issues, both for Passive House and embodied carbon because it's within their value system.”

This value system informs every aspect of 79 King. The Live Give Play team are pushing the envelope on their material choices and design standards to not only make better buildings, but also to enhance the lives of residents, both within the building and in the larger community beyond.

All images courtesy of BKSK Architects LLP