Loosely defined as the area between Central Park and the Hudson River and from 59th to 110th Streets, Manhattan’s Upper West Side has been one of the desirable places to live in New York City for decades. Despite its proximity to the busy streets of Midtown, the Upper West Side is known for its relatively peaceful and treelined streets, stately townhouses, and luxurious apartment buildings, as well as avenues that are made up largely of pre-war four- and five-story buildings with retail spaces on the ground floor. Perhaps nowhere else in New York City has an area fought more assiduously to preserve so many buildings from the early twentieth century, leading to dozens of blocks that have been designated as part of one of nine separate historic districts in the neighborhood and relatively little new development, particularly along Columbus Avenue.

One major exception is Charlotte of the Upper West Side, which was completed in early 2023. Located on Columbus Avenue between West 82nd and West 83rd streets, the nine-story condo building was developed by The Roe Corporation, designed by BKSK Architects LLP, and has been certified by the Passive House Institute as a Low Energy Building. “Our client likes to point out that this district has only a handful of new buildings,” says Todd Poisson, a partner at BKSK. He also notes that it is one of the first new Passive House buildings to be built in a landmark district in Manhattan.

A Shaded Solution

Though Charlotte replaces a three-story commercial building that was constructed in 1961, most of the buildings on the property’s block were built in the 1880s and are five-story tenements. A typology that defines much of the cityscape of Manhattan, these buildings are made of brick, cast iron, stone, and terracotta, while their façades are dotted by rows of punched windows that give the streetscape a sense of symmetry.

Given the distinct aesthetics of the block and the neighborhood’s penchant for historic preservation, BKSK recognized that the project needed to firmly align with the context of its surroundings, as evidenced by the building’s fenestration pattern and brickwork. The team took inspiration not only from the immediate block, but from the surrounding historical district. As Poisson says, “That really inspired us to create a façade that was worthy of the district, that contributed to this district, and lent itself to the Passive House ideals.” This homage to the area was appreciated by the city’s Landmarks Preservation Committee (LPC), Poisson says. “They share our happiness with this building. We really feel it’s a triumph for this district,” he adds.

The resulting facade features regularly spaced larger-than-typical high-performance windows that are partially obscured by a distinctive terracotta shade system, enabling the building to stand out architecturally without disrupting the tapestry of the streetscape. This visual balance is achieved, even though Charlotte, at nine stories in height, is slightly taller than the adjacent buildings.

Of course, the fenestration system that defines the exterior of the project so saliently was not simply a choice to please the LPC. As BKSK associate William Russell noted during the fourth episode of the Urban Passive House series, which was produced by New York Passive House and Passive House Accelerator and aired in June 2023, the system also resolved several issues affecting daylighting and thermal performance that may impact other Passive House designers, especially in urban environments.

Although traditionally sized punch openings would have been favored by the LPC and provided sufficient thermal performance, BKSK found that they didn’t distribute light evenly throughout the building’s interior spaces and obstructed views of the city below. For a luxury condominium, this was a problem. Alternatively, floor-to-ceiling glazing provided better views and increased the amount of light in the units, but it also increased the cooling load of the building (as the building is oriented to the southeast), created glare spots, and would have been virtually untenable in a landmarked district.

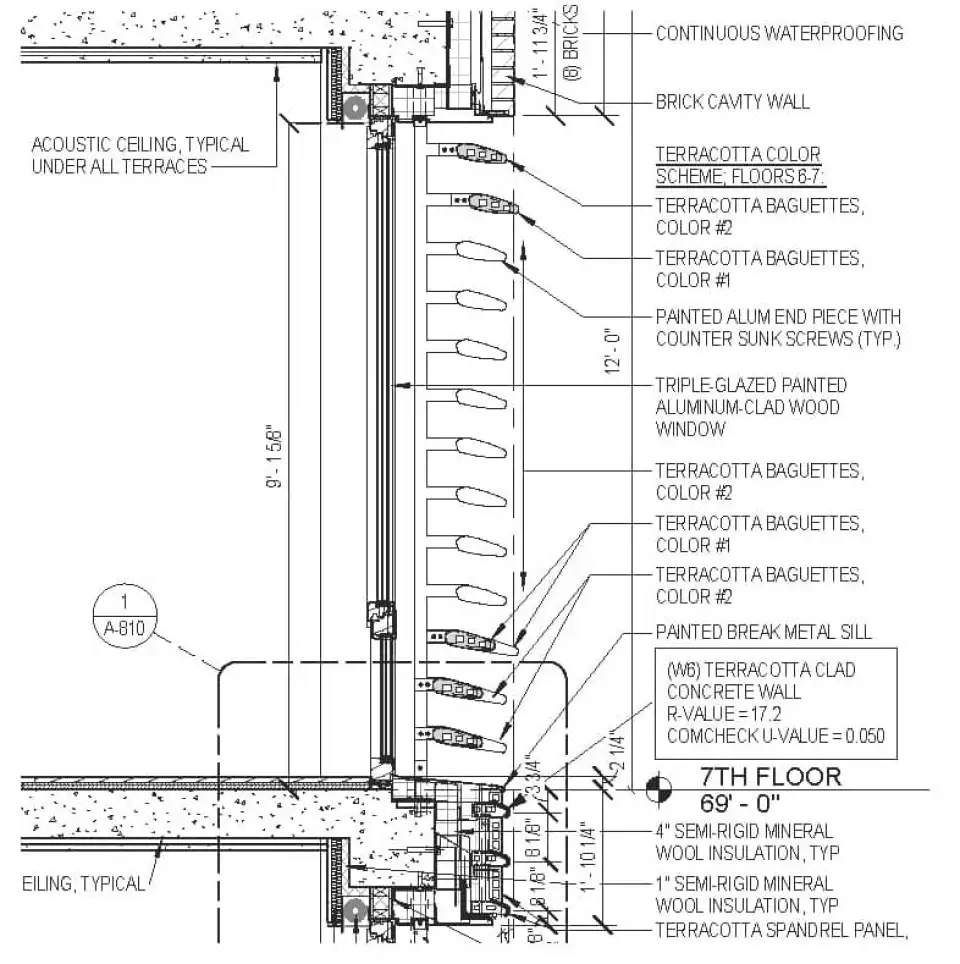

The solution was to find a middle ground that included large expanses of triple-pane glass with a sunshade system to ensure good views, good daylighting, and excellent thermal and acoustic performance (see Figure 1). Without such a system, the cooling demand would have been above the allowable metric, according to the Passive House Planning Package (PHPP). As Sam McAfee of Zola Windows notes, Zola supported the energy modeling and design team with multiple iterations of Flixo energy models and glass package thermal performance and acoustic analysis. The larger-than-typical windows put a lot of stress on the hardware, which approached the limits of their specifications. “This was an intense and highly detailed project spec where we were able to find the balance between the Passive House performance needs, acoustic requirements, design requirements for interior oak and large glass, and the city's landmark designation for this site and balance it with the hardware max specifications, glass weight, frame material limitations, and supply chain availability issues,” McAfee says.

McAfee notes that “Passive House performance numbers required the use of our enhanced ThermoPlus Clad frames.” The project also demanded specialty glazing. Zola used a colorless Guardian Ultra Clear glass with improved acoustic performance. The glazing was also outfitted with low-E coatings to limit heat gain. Additionally, the units are filled with either argon or krypton gas, depending on the window size and location, and all feature asymmetrically sized Super Spacers—16 mm in one cavity and 20 mm in the other—to minimize exterior noise. “Since the glass sizes began to reach the limits of the hardware available, we had to utilize a unique approach to achieve the specified acoustic stoppage of the glass,” McAfee says. “Doing this boosted the acoustic performance of the thinner, lower-dB laminated glass packages to 36dB and 43dB. This avoided the need to use thicker, heavier, and much more expensive glass, which would have caused other operational hardware issues.”

The windows’ exterior insulation is covered by aluminum, while the sunshade system is composed of terracotta baguettes (as the slats are called), which are suspended on a post from the slab above and hung like a curtain wall with brackets that cantilever off the post, holding the baguettes in place. The terracotta itself is from Sannini in Italy. Magnesium pigment was added to modify the color and to better match the palette of the neighborhood. Meanwhile, the brickwork, which was also heavily influenced by the color scheme and history of the Upper West Side, was installed by the project builder, Hudson Meridian Construction.

Not everything was smooth sailing, largely because of a combination of the project’s idiosyncrasies and supply chain issues that arose during the pandemic. Zola drafted the install shop drawings for the project in-house, and McAfee says that there were seven or eight separate teams providing input. “We ended up doing dozens of iterations of the shop drawings to get it right,” he says. “Getting the flashing details in conjunction with Passive House airtight wall details, window install sequencing, and the ceramic baguette rainscreen connection details was no small feat.”

McAfee also notes that production was unable to get the krypton gas that was specified for a portion of the project and required to meet the Passive House certification. “This was not discovered until the windows were actually on-site and partially installed,” he recalls. “So, the Zola team came together to solve the problem by purchasing the necessary equipment, sourcing a large amount of krypton gas out of the Midwest, and devising an on-site protocol to replace the argon fill gas with 90% krypton fill gas. The team pretty much set up a portable glazing factory on the project site and changed out the gas in the field. Pretty amazing warranty support!”

Passive House as an Amenity

Though the exterior aligns with the historical context of the neighborhood, the interior of the building is very contemporary and very posh. The project is comprised of six full-floor homes and one duplex penthouse outfitted with multiple terraces—some private, some for all of the building’s residents. The residence on the second floor is home to a private garden space, while the floors above contain private terraces off the primary suites that look down to the garden. All residences are accessed via elevator, contain four bedrooms, and enjoy 50 feet of frontage along Columbus Avenue—as does the retail space on the ground floor that is outside of the passive envelope.

Charlotte is unquestionably a luxury condominium. The building’s finishes and furnishings are exquisite, the building’s list of amenities is very impressive, and the number of residence features goes on for days. What many within the Passive House community will quickly discern is that many of the selling points that make Charlotte such a desirable place to live are firmly rooted in Passive House design.

It is quiet because the building is outfitted with continuous insulation, airtight construction, and triple-pane glazing. It offers optimal thermal comfort because of the insulation, airtight construction, glazing, and thermal bridging free detailing. Residents use less energy on heating and cooling for these same reasons, which also allows for the Mitsubishi VRF system to be shrunk way down to three fan coil units that are ducted and concealed in the space. Meanwhile, the air inside is better conditioned and healthier because all airflow entering each apartment comes from outside and first passes through an ERV system manufactured by Zehnder before being filtered and blasted with ultraviolet light. The filtration removes dust, smoke, irritants, and allergens from the air, while UV light eliminates most mold, bacteria, and viruses.

Passive House was also a major selling point for the developer, who was particularly attracted to the idea of eliminating mechanical systems on the roof, as this simultaneously resolved several issues. The LPC does not allow mechanicals to be seen from the street, so making them smaller makes them far easier to hide. Additionally, smaller mechanical systems on the roof means more space that can be included within the shared rooftop space, the penthouse, or penthouse’s private terrace.

On account of the VRF system being so small, the team was able to use what are known as “suitcase condensers” for each unit that can be stacked vertically. This freed an estimated 200 ft2 of rooftop space. “Literally, every square foot that we can save for mechanical equipment is another square foot of saleable penthouse area,” Russell says. “At $3,000 per square foot, it adds up pretty quickly.

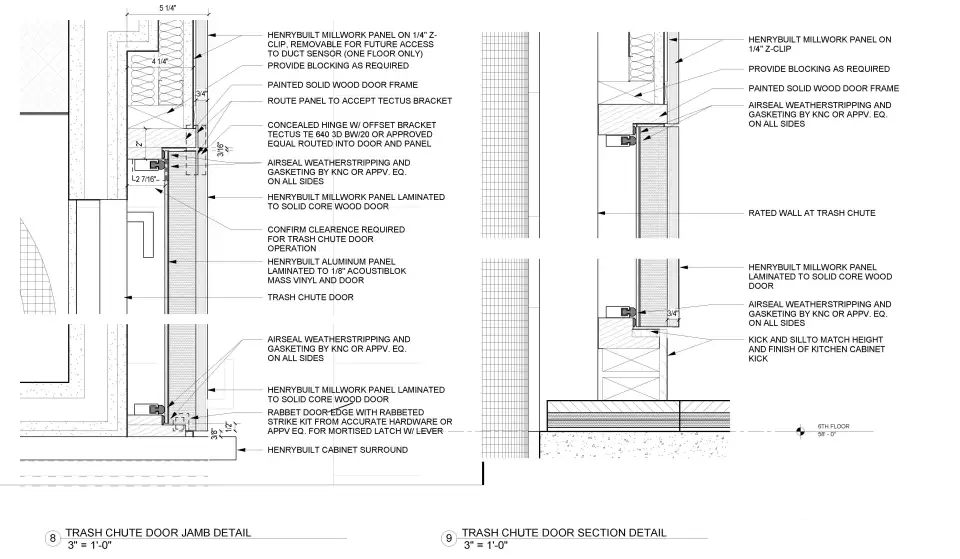

The Art of Detailing a Garbage Chute

Detailing garbage chutes in New York City can be tricky, as the city’s building code requires these means of rubbish conveyance to be at least 24 inches by 24 inches and equipped with self-closing hopper doors that have a fire resistive rating of one hour unless situated in a room that is separated by a self-closing door constructed of incombustible material. For Passive House construction, the chutes and the rooms containing the chutes are oftentimes outside of the Passive House envelope, making the seal around the door vital to overall airtightness. In instances where only the chute is outside of the Passive House envelope, this means designing a hopper door that is airtight.

As all units in this project are full floor, the design team decided against creating a separate room on each floor with access to the garbage chute. Instead, the chute runs adjacent to each unit’s kitchen, and the hopper for each floor is hidden behind an airtight door (as seen in Figure 2). “We came up with this system, which is essentially an exterior level door, with weather stripping all around and specialty hinges and a panel from our kitchen supplier attached to it, that seamlessly blends into the kitchen around it,” Russell says.