You won’t end up in Callicoon by accident. Located deep in the Catskills and just a few miles downstream from where the east and west branches of the Delaware River converge, Callicoon has long served as a haven from the oppressive summers of New York City and a destination for those living nearby who want a night out. While the hamlet’s main strips continue to have a certain nineteenth-century rail town charm, they are now home to several new restaurants, as well as a tasting room for a distillery. Less than a mile outside of town, up a road surrounded by a dense forest that is home to an abundance of deer, foxes, and bears (allegedly), one will also find Seminary Hill Orchard & Cidery—the first cidery, brewery, or winery in the world to receive Phius certification.

Cidery Celebrates Holistic Agriculture and Architecture

Designed by Cold Spring-based River Architects, built by Poughkeepsie-based Baxter, and certified PHIUS+ 2018, the two-story, wood-frame cidery is virtually all-electric (there is a propane-fueled backup generator) and extremely energy efficient, but the focus on sustainability does not begin and end with the structure. Rather, this ethos extends into every facet of the operation, including pest control within the orchard, the facility’s greywater system and dark-sky compliant lighting, and the menu. Responsible stewardship of the land is paramount to the operation of Seminary Hill and founder Doug Doetsch even worked with the late Michael Phillips, one of the most celebrated orchardists in the world, to create ideal soil conditions for apples using a methodology that relies on organic and holistic agriculture.

Completed in 2020, the cidery overlooks the 62-acre orchard containing the dozens of varietals that go into making a well-rounded cider, as well as the clocktower of what was once St. Joseph’s Seraphic Seminary (the cidery’s namesake) but is now the Delaware Valley Job Corps Center. In the distance are the rolling hills of northeastern Pennsylvania. While the views from the top of the hill are no doubt majestic, the cidery is a marvel onto itself. Built into the side of a hill, it combines rustic and timeless forms that celebrate the agrarian history of the Catskills region with materials that come from the area. The tables within the restaurant space are made from trees that were felled to make way for the cidery and orchard; the façade of the bottom floor prominently features bluestone from nearby quarries; and much of the interior and exterior facades on the top floor, decking, and roof consist of the larch underwater pilings that once supported the Tappan Zee Bridge. The slatted portico at the cidery’s entrance is also made of the reclaimed larch, while the decking is Eastern red cedar.

The building houses the cidery, tap room, and restaurant and is of “bank barn” design, which is not only consistent with the architectural heritage of the area but serves multiple purposes. It allows on-grade access at both levels. It also neatly separates the space where the cider is produced (on the bottom floor) from where it is consumed (on the top floor). This has clear organizational advantages. On the one hand, cidermakers have on-grade access to the orchard through high-performance overhead doors and don’t have to trudge through the dining room to get to the production space. On the other, it creates two distinct zones within the building, one optimized for people and one optimized for fermentation—a notoriously finicky process that produces the best results when temperatures are kept stable and the environment is free of vagrant microbes.

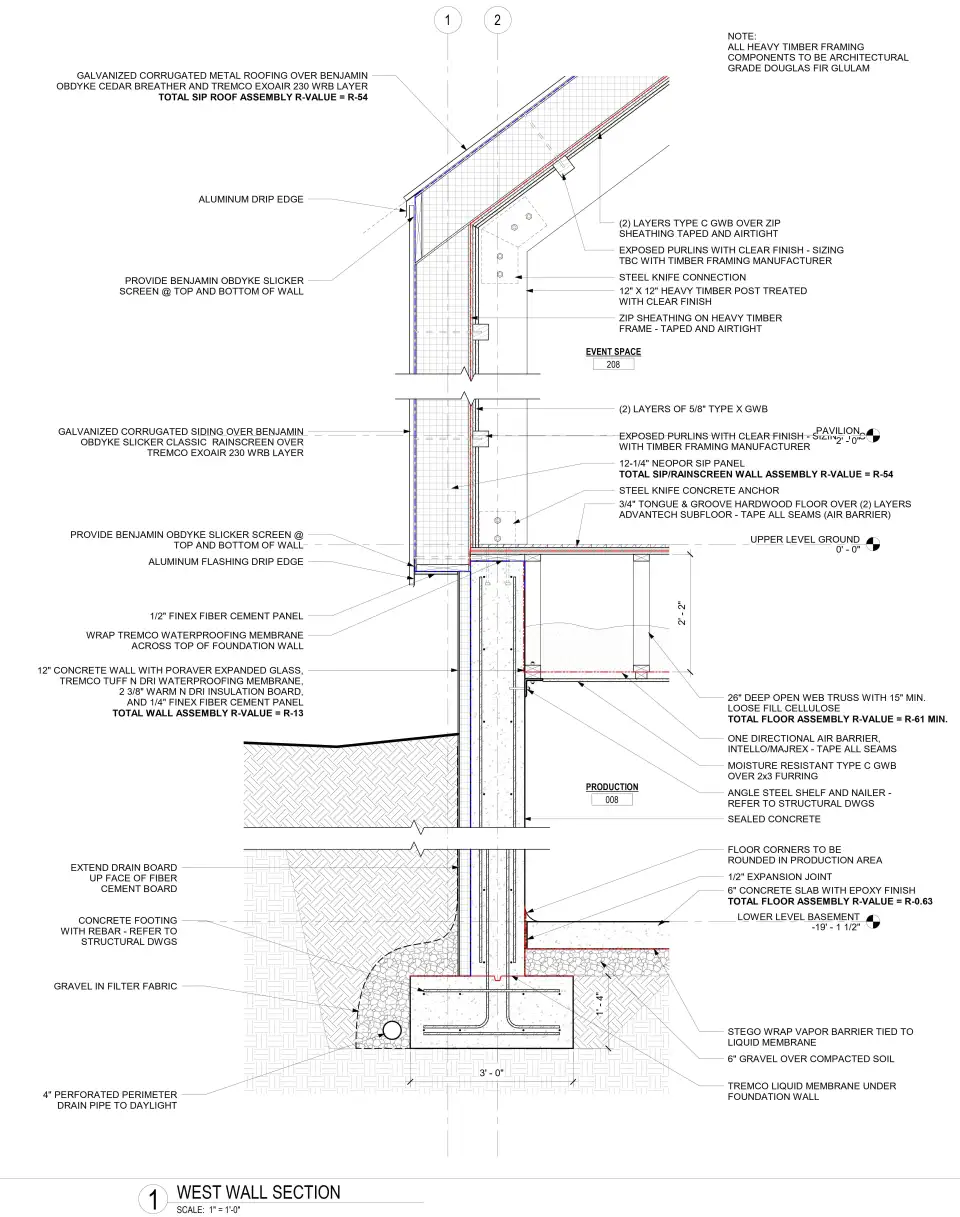

The bottom floor is also home to an unconditioned aging cave. James Hartford, the architect of record on the project and partner at River Architects, notes that the aging cave may not fall within the 7,542-ft2 Passive House envelope, but Passive House principles were certainly employed in its design. Intentionally left without sub-slab insulation and dug into the hillside, it takes advantage of the heat-regulating effect of the earth and remains at a near constant temperature no matter the season. It also takes the gross area of Seminary Hill up to 9,350 square feet.

The upper floor of the building is approximately 3,000 square feet and is home to the kitchen, tasting area, and restaurant, which can also serve as an event space. It also leads out to an open-fire grill and a wraparound balcony that can be accessed by south-facing, high-performance doors, as well as another high-performance door on the building’s east side.

While the food and the cider are exceptional (particularly the Susan’s Semi-Dry from 2019), the view is once again a central experience when coming into the space due to the picture window opposite the entrance. Hartford notes that this window and the rest of the glazing along the wall are triple-pane and oriented due south, allowing them to take advantage of thermal gains during the region’s notoriously cold winters. Neopor SIP panels provided by Farmington-based New Energy Works provide the top floor with continuous insulation, while the open web trusses in the attic space have been insulated with loose-filled cellulose. The SIP walls and roofing have an R-value of R-54, while the roofing above the attic space is a more robust R-87. To avoid the risk of overheating in the dining area or on the adjacent balcony, a canopy can be unfurled to both cover the balcony and provide solar control for the remainder of the southern wall’s glazing.

Overheating was also a concern due to the commercial kitchen. As anyone who has ever worked in a restaurant will know, these frenzied spaces are hot, suffocating, and loud. Even the lull between lunch and dinner rushes rarely offers a reprieve from the chaos. The kitchen at Seminary Hill, however, is almost silent. There is barely even a discernible difference in temperature upon entering. If one were blindfolded, it could easily be mistaken for an extension of the dining room. Every appliance, including the range, is electric, which dramatically reduces the amount of heat waste and allows the space to be conditioned by a single mini split from the building’s Mitsubishi heat pump system. As in the rest of the building, ventilation and heat recovery is provided by a Renewaire ERV.

The building’s second climate zone, which is designed to stay around 60° F (16° C), begins as one enters the stairwell to the facility where production takes place. Despite being cooler and dominated by a more industrial aesthetic, largely due to the heavy machinery, cast-in place concrete walls with Poraver glass aggregate, and galvanized steel stairs, the space is awash in natural light. Even the small office space on the mezzanine receives natural light through an interior window overlooking the space where the apples are stored, processed, and fermented. When coming from the field, the space can also be accessed through southern-facing overhead doors manufactured by Hörmann. When closed, Hartford notes that they rest on a customized thermal break that is made of a high-density EPS foam strip with poured epoxy wear surface that allows heavy wheel traffic to pass between the concrete within the building envelope and the concrete outside.

Directly below the offices is the mechanical room for the entire facility, which contains components for the ERV, the heat pump system, and a Proterra heat pump water heater manufactured by Rheem. In keeping with Passive House design, it is extremely small given the size of the complex, perhaps no more than 50 ft2. The adjacent walk-in cooler, however, needs to be large because it does triple duty serving as the walk-in refrigerator for the restaurant, the keg room for the bar, and the space where many apple varietals are stored for weeks or even months after harvest to develop better flavor (a process known as “sweating”).

Many other steps in the cidermaking process are far less energy intensive, though they do present unique challenges while operating in such an airtight facility. Passive House design should sound like music to the ears of fermenters who want to keep their spaces at a constant temperature and free of unwanted yeasts and bacteria. However, as yeasts eat sugar and create alcohol, they also produce a lot of carbon dioxide that can overwhelm even large ventilation systems. Moreover, the team at Seminary Hill use CO2 in place of liquid sanitizers to flush their tanks. While this avoids the use of chemicals to keep their fermenting vats free of wild yeasts and harmful bacteria, the process can also make it difficult for the ERV to keep up. To mitigate the issue, an ancillary system has been arranged that involves running a flexible hose from the area housing the vats under the overhead doors during periods of high CO2 concentrations.

The production floor is also the main stage where the real artistry of cider production takes place as head cider maker Stuart Madany blends different varietals to create a more balanced cider. The cider is then filtered to eliminate any sediment. At this point, the cider may go into oak casks and be aged, it may be bottled and pasteurized, or it may be put into kegs that will be consumed upstairs in the cidery’s tasting room. Though many of these processes are energy intensive, the building is equipped with a solar water heater system and 98-panel, 36.26-kW photovoltaic array that produces approximately 44% of Seminary Hill’s total energy use. Additionally, a greywater recycling system is used to wash the fruit and equipment and further cuts down on waste.

Contrary to industrial agriculture, which prioritizes yield size and homogeneity, Seminary Hill places a greater emphasis on sustainability and locality, together contributing not only to the production of exceptional ciders, but in the design of the facility, too. Whether through the bank barn design, the use of local bluestone and reclaimed wood, or the respect for the land, Seminary Hill is intimately tied to place and to the community.