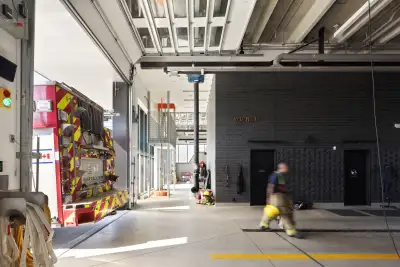

Vancouver’s Fire Hall 17 is located on Knight Street, one of the primary trucking routes leading in and out of the city. For years, the building had been sinking into obsolescence and was in the worst condition of all fire halls in Vancouver. Firefighters complained of being woken up as trucks shook the building and rattled the windows throughout the night, there was no cooling in the summer, and the building was drafty in the winter.

Exceeding Expectations in Canada’s First Passive House Fire Hall

“Firefighters hated working out of the building,” says Vancouver Manager of Energy and Utilities Craig Edwards. Beyond being uncomfortable, Edwards says that the original facility, which was built in 1954, had become too small to meet the needs of the community. Like many older buildings in Vancouver, it also no longer met the city’s seismic code.

While it had long been a foregone conclusion that the old Fire Hall 17 had to be demolished to make way for a new facility, what that new building would look like and how it would perform was an open question. This changed in 2016 when Vancouver passed the Zero Emissions Building Plan, which gave the city until 2030 to bring operational greenhouse gas emissions in new buildings down to zero.

Built into the motion, Edwards explains, was language that the city “would build all our city-owned buildings to be either Passive House certified and use no fossil fuels or designed to an alternative zero emissions standard. We've been building all of our buildings to Passive House and one hundred percent electric ever since.”

The first such project was Fire Hall 17. It produces 99.7% less greenhouse gas emissions than the building it replaced.

Creating a High-Performance Culture

In his current role with the City of Vancouver, Edwards is responsible for finding and implementing means of reducing both energy and greenhouse gas emissions in the city’s portfolio. For Vancouver, this amounts to approximately 600 properties, covering civic municipal buildings, theaters, libraries, police stations, and fire halls, as well as warehouses and pieces of commercial real estate. This is not a new or daunting task for Edwards, as he has performed similar work for various government agencies for over 20 years, and he has been with the City of Vancouver for approximately half of that time.

“I've always been lucky. Everywhere I've worked I’ve been able to set the highest standards for our government-owned buildings, and then aimed for them,” he says. “The best keeps changing, and the buildings keep getting better.”

Since the Zero Emissions Building Plan was passed by the Vancouver City Council, the city has completed four Passive House projects. “They're the absolute best performing buildings that we've got,” Edwards says. “They blow the performance of all others out of the water.”

In addition to the four Passive House buildings that are already built, there are four under construction, as well as another four currently in design. Of the twelve total, three of them are fire halls. Other building types include a seven-story artist hub and gallery, a large community center, and several mixed-use buildings—including one that contains a school being built for the Vancouver School Board and a city-owned building with childcare and housing under one roof.

Though challenging, Edwards says that finding ways to apply Passive House principles to unique building typologies has encouraged innovation within the field of design. Moreover, these projects, and the increased rigor of Vancouver’s building code, are having a transformative effect on producers of building components.

“Passive House in particular has really caused a shift and encouraged local manufacturers to step up their game in a number of areas,” he says. As one example, Edwards says there were no local manufacturers of Passive House certified windows just a few years ago. There are now three: Cascadia, Innotech, and EuroLine Windows & Doors.

There’s also a great success story for heat recovery ventilators. Initially, the only certified HRV units capable of handling the ventilation volumes Edwards needed for municipal projects were produced by Swegon, which is based in Sweden. However, a local manufacturer named Oxygen8 recognized Vancouver’s growing need for HRV units, started building them, and recently had several models certified by the Passive House Institute (PHI).

Edwards notes that not everything manufactured by the window companies or Oxygen8 is built to comply with Passive House standards. However, even their models that are not certified still perform exceptionally well, especially when compared to regional competitors outside of the city and province.

“It’s really stepped things up.”

Some Experience Required

As the regulations that allowed for this sea-change to occur were in the works, preparations for the redevelopment of two city-owned buildings were also underway. One was a four-story, wood-frame residential building named Roddan Lodge. The other was Fire Hall 17. While Roddan Lodge was set to be replaced by an 11-story, concrete building of the same name with more than 200 affordable housing units and community services, the city decided not to strive for Passive House certification for several reasons, one of which concerned the difficulty in sourcing windows at the time.

After passing on Roddan Lodge, the city issued a request for proposal (RFP) for the new Fire Hall 17. The RFP required it be built to passive standards. In addition to being the first city-owned building in Vancouver to pursue certification through PHI, the project also was to become the very first fire hall in North America to be Passive House certified.

As Edwards reflects, it was the more complicated project of the two. In addition to being an uncommon building type, Fire Hall 17 is also designed to be a two-crew fire hall that is home to a communications hub for the City of Vancouver and a training center with a full-size hose tower. The fire hall is what is known in Canada as a post-disaster building, which requires additional efforts to ensure the building remains operational following a disaster like an earthquake or a flood.

If there was any firm in British Columbia that had enough experience with passive design to take on the project, it was hcma architecture + design. However, what constituted experience with passive design in 2016 is a lot different than what it means today. While the firm had already worked on several passive projects when they submitted their proposal and won the contract, construction on their first Passive House had only begun two years previously—in 2014. That project, a sixplex condominium known as North Park Passive House, was also the first condominium building in Canada to receive Passive House certification.

As of 2016, the number of Passive House buildings under construction or completed for all of Vancouver had yet to reach double digits.

Modeling the Fire Hall

According to hcma’s Director of Building Performance Elise Woestyn, high-performance building had barely entered into the Canadian imagination when she immigrated to B.C. in 2012. In Woestyn’s native Belgium, Passive House and low-energy buildings have been commonplace for around 20 years, and she arrived in Canada already familiar with passive principles and trained to be a Passive House practitioner. Despite her personal experience with passive principles and the firm’s previous work on Passive House projects, Woestyn and the team at hcma still recognized that modeling Fire Hall 17 was going to be anything but straightforward.

First and foremost, the massing of the fire hall had to optimize what is known as turnout time, which is the period of time from the first notification of an emergency to the point at which vehicles leave the facility. Woestyn explains that this is one of the most important operational metrics of any fire hall and that the facility was designed so that any firefighter could go from any point in the building to a truck in 60 seconds or less. This led to some interesting geometries, but the team was able to remain true to the principles of Passive House and to keep energy use intensity low with minimal compromise.

A more significant concern arose when the team began designing the apparatus bay (the space where emergency vehicles are housed), which had to be conditioned for operational needs. As Fire Hall 17 had to accommodate four drive-through bays each equipped with two overhead doors, which are notoriously leaky, the team worried about their impact on both the building airtightness and space heating demand. Woestyn notes that she has heard of certified Passive House projects where a few overhead doors have been used—but not eight.

Another factor affecting the heating demand was the number of unavoidable thermal bridges. Post-disaster buildings are designed to have an extremely long service life and must be especially durable. Consequently, the design required enhanced seismic resilience that interfered with some of the design techniques that go into creating a Passive House building. For example, the design team could not put insulation beneath the building’s footings (though they did insulate the rest of the foundation), and thermal breaks between certain connections were not on the table. “Each time we would ask the structural engineer to introduce thermal breaks in the structure, they would just laugh at us,” Woestyn recalls.

Process loads were also considerable for two distinct reasons. First, the building is constantly occupied, so systems need to be operating 24/7, Woestyn says. Second, on account of being a post-disaster building, the fire hall also serves as a citywide IT hub with equipment that has to run constantly. Such energy-intensive IT, communications, SCADA (supervisory control and data acquisition), and traffic control equipment further adds to plug loads and generates a significant amount of heat.

The team worked with PHI to find solutions to these design challenges, and ultimately decided to split the building into two adjacent and self-contained zones with separate PHPPs and different conditioning requirements. Zone A consists of the firefighters’ quarters and offices. Like more conventional Passive House buildings, it is designed to remain at 20°C. Zone B, which consists of the apparatus bay and hose tower, has a heating setpoint of 10°C in winter and a cooling setpoint of 25°C in summer. Additionally, PHI allowed the team a great deal of levity with respect to meeting their airtightness score in Zone B, where a placeholder target of ACH50 5.0 was set that allowed the team to confirm the space heating demand target could be met. However, the standard space heating energy demand target of 15 kWh/(m2a) was not relaxed.

Building the Fire Hall

Despite the complexities in modeling, Woestyn says that the assemblies are very conventional—though each zone is distinct. For Zone A, the concrete slab on grade is insulated with 8 inches of extruded polystyrene (XPS) insulation (except for beneath the footings). The assembly has an average R-value of 40. In Zone B, the team sandwiched a 2-inch layer of XPS insulation between the structural slab and a sloped concrete topping that allows drainage, but notably less thermal resistance. It has an R-value of 11.

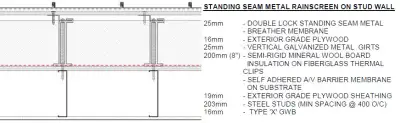

Most above-grade exterior walls are steel framed with an 8-inch exterior layer of Rockwool mineral wool (see Figure 1). This assembly has an R-value of 34. The wall assembly for the training tower is notably different, as it is constructed using concrete and outfitted with exterior XPS insulation. Woestyn notes that the team opted for XPS because it has a higher R-value per inch, allowing the insulation layer to be even thinner. The average R-value for this wall assembly is 20.

The roof assemblies for Zone A, the apparatus bay, and the tower are also each different. The roof for Zone A has an R-value of 98 and consists of a 16-inch layer of polyisocyanurate, sloped EPS, and SBS roofing over a metal deck; the apparatus bay’s roof assembly is reinforced concrete with sloped EPS, 5 inches of polyiso, SBS roofing, and 2 inches of XPS (R 40); and the hose tower’s roof assembly is a reinforced concrete slab with 5 inches of polyiso insulation and a sloped EPS insulation package (R 36).

For the various wall and roof assemblies, the team opted for a self-adhered membrane to serve as an exterior air barrier. “Wrapping the building on the outside is typically much easier than dealing with all the junctions and connections with an interior air barrier strategy,” Woestyn says.

However, wrapping the building was easier said than done, which became apparent midway through construction. What began as a brief pause to run diagnostic tests and look for air leaks turned into a three-month hiatus when they found far more leakage than they had hoped they would. Some of the main culprits included the connections around the windows, air barrier transitions between different assemblies and zones, and electrical conduits connecting the two zones. One of the most significant sources of leakage was the service entrance for the building’s electricity, which hadn’t been sealed at all. Another major discovery was that the steel decking in the roof assembly was corrugated, which made it difficult to effectively seal with tape alone. To remedy the latter issue, the team decided to use liquid-applied flashing instead of tape alone. Once these penetrations and weak points in the air barrier were sealed, the team was able to meet their ACH50 targets in Zone A (0.6 ACH50).

Within the apparatus bay, the team was able to achieve an airtightness score of 0.96 ACH50, just slightly lower than the 1.0 ACH50 requirement for EnerPHit certification. Remarkably, this was accomplished without PHI-certified overhead doors, as the team encountered difficulties when striving to source these components. They found a solid alternative from Cloplay Garage Doors, a U.S. manufacturer that sells a model with thermal breaks.

For windows, the team was able to source triple-pane, PHI-certified aluminum curtainwalls by Raico (THERM+ 50). In addition to providing daylighting, these windows are a crucial part of the project’s passive shading strategy because the fire hall stretches from property line to property line, leaving no room for overhangs. The window systems are outfitted with electrochromatic glass along the east-, west-, and south-facing sides of the building. The electrochromatic glass, which contains krypton gas in the cavities between panes, has a high solar heat gain in winter when it’s not tinted. In the summer, the tinting protects against overheating.

Working Towards Zero

The mechanical systems for the building are entirely electric and the heating and cooling rely on three water-to-water heat pumps that Woestyn describes as being almost residential-size. They are connected to a geothermal field in the front apron that consists of 15 boreholes.

“The city loves it,” Woestyn says. “It’s very low maintenance.” Had the fire hall been built to code minimums, she continues, the project would have needed 70 boreholes. Given the space limitations of the site, this would not have even been possible.

For ventilation, there are six ERVs throughout Zone A that include five Swegon Gold RX ERVs and one Zehnder Comfoair. Within the apparatus bay is a Nederman extraction system that connects the trucks’ exhausts to an exhaust fan, which clears the area of noxious fumes. There’s also an exhaust fan in the hose tower to enhance drying after training sessions.

As noted above, the fire hall is a city-wide IT hub, and the equipment to support the hub generates a lot of heat. Rather than waste it, the energy is captured and used to reduce strain on the domestic hot water system, which is primarily warmed by two air-source heat pumps. In addition to the equipment for the IT hub, the fire hall is also home to a “gear extractor,” which is a specialized piece of equipment used to clean the firefighters’ gear. Woestyn says that the extractor uses a lot of energy, but that the city was adamant about using a specific model for the sake of familiarity for staff and maintenance crews. Moreover, there weren’t a lot of options for super-efficient models because it is a fairly niche piece of equipment.

Because the gear extractor and the IT equipment collectively use so much energy, the total loads for the building go beyond the capabilities of the 85.8-kW rooftop photovoltaic array. However, according to Edwards, the fire hall still uses about 68 kWh/(m2a), which is far more efficient than any other fire hall under the city’s management. Per square meter, the energy cost to operate Fire Hall 17 is approximately 15% of other Vancouver fire halls currently in operation. When the process loads are excluded, the rooftop array more than covers the amount of energy used by the building.

Exceeding Performance Targets

“Plan to exceed the performance targets,” Woestyn says when asked if she has any advice for designers tasked with building a passive fire hall. Having a higher ceiling will provide breathing room should one run into a pedestrian problem like a component not working right. It can also help should a once-in-a-generation pandemic occur midway through construction.

Second, she recommends keeping it simple. Beyond EUI and massing, simplicity can also mean reusing details rather than doing everything from scratch. In addition to streamlining design, it allows the crew to become more attuned to how the assemblies are put together and can make construction run smoother.

Finally, Woestyn says communication is vital and that it’s important to have buy-in from everyone involved with the project, including the subs and the trades. Everyone should understand the basic principles of passive design: what thermal bridges are, why maintaining a continuous layer of insulation is important, and why it is integral that every penetration be reported and sealed. The only way everyone on the site will understand these principles is if they are clearly communicated to them.

Since being completed in 2021, the project has been a picture of success that other fire halls around Vancouver hope to emulate. “It’s running itself,” Woestyn says. Consequently, the maintenance staff love it.

The city also loves it because data has regularly shown that it performs significantly better than other fire halls in Vancouver. Despite being more than twice the size of the previous facility, the new Fire Hall 17 uses approximately 90% less energy than the previous fire hall and produces less than 1% of the greenhouse gas emissions.

Most important of all, the firefighters are pleased with the change. According to Woestyn, it has been performing even better than the model in terms of thermal comfort—especially in the apparatus bay, where the temperature hovers around 18°C year-round. Meanwhile, Edwards says that one of the biggest complaints about the old fire hall, the noise from Knight Street, has been completely eliminated.

“With the new building, they love it because it’s solid,” Edwards says. “It doesn’t shake and it's so quiet that you can’t even tell that there are trucks going by outside.”

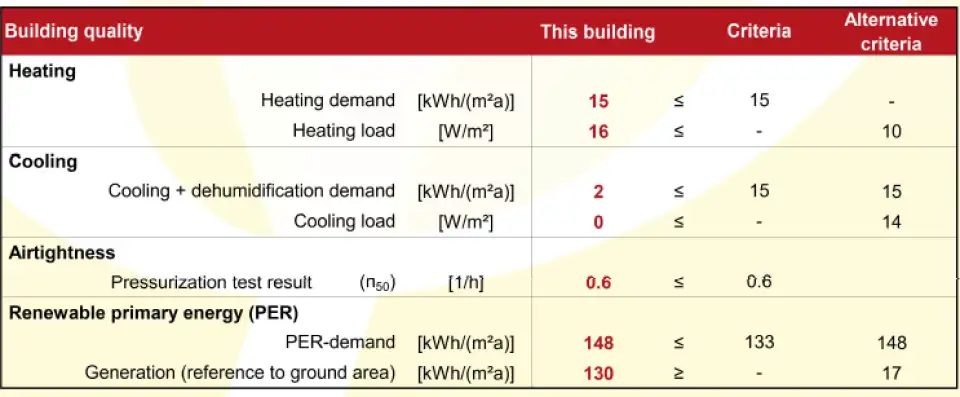

Passive House Metrics