Those who have worked in the world of building science or high-performance construction for more than just a few days will be familiar with the phrase “it depends.” It can be frustrating when you hear it for the tenth or eleventh time in an hour, especially if you are just getting your bearings in the world of building science. It can feel like no one wants to answer your questions.

Four Big Questions Every Prefab Straw Panel Manufacturer Answers Every Day

However, “It depends” is not meant to be evasive or dismissive. It is a polite way of saying that your question is not specific enough to produce a straightforward answer, and that you need to provide more information before a proper answer can be given.

Savick Founder Sam Kondratski regularly finds himself relying on the phrase when fielding questions about straw, as this is the insulating material of choice for the straw panels that Sam manufactures within his modest facility near Edmonton, Alberta. Some of these questions will come up in the below article but first let’s introduce Sam, Savick, and straw.

Savick at a Glance

As Sam recounts, he knew that he wanted to start a business before finishing high school. While a bite by the entrepreneur bug is common, he didn’t just want to run a company. As he began taking business classes, he realized that he had a deep appreciation for things like supply chain management, accounting, and improving efficiencies in manufacturing—the real nuts and bolts that make up a company.

In addition to entrepreneurship, Sam also had an interest in construction, and he ultimately decided to form a business within the building sector. He wanted to create more housing and to build it to a higher standard, but he also set for himself three objectives that continue to be the core directives of the company: “We’d like to store carbon in more buildings; we would like to have more energy efficient spaces; and we would like to have more comfortable spaces for people,” he says.

While Savick was born with these objectives in mind, Sam did not initially have a clear idea of how he would meet them. Eventually, he realized that every fall his home in Canada’s breadbasket, Alberta, was literally surrounded by tons upon tons of underutilized agricultural residue: straw.

As Sam succinctly put it: “Straw is cheap. We have a lot of it. Homes are expensive. They need insulation. Let’s figure out a way to get straw into those buildings.”

Straw at a Glance

Once the seeds from grain plants like barley, rice, and wheat are harvested, the leftover stalk is then cut at the base and left to dry in the sun. This is straw. Once the straw has had enough time to dry out, it is then baled, though some straw typically remains in the field to benefit the composition of the soil and return nutrients to the ecosystem as it decomposes. After being dried and baled, the straw can then be stored until it is time to be used.

Even though farmers do not harvest all the straw from their field and opt to rotate straw-producing plants with other crops, the amount of straw produced each year in North America is enormous. As a conservative estimate, Sam says that Canada produces enough straw to insulate more than 1 million homes each year, even though the nation only builds around 200,000. The ratio in the United States is similar.

Given its composition of lignans and cellulose, straw is not particularly attractive to pests or microorganisms. It contains high levels of silica, which is naturally fire-resistant. So long as it is kept dry, it does not provide a harbor for mold. Unlike hay, which contains loads of starches and sugars, straw is not used for animal feed. Instead, it has been used in bedding, as mulch, and (traditionally) as a building material. In extremely dry climates, it can be mixed with clay or mud and turned into bricks. Outside of these very specific and rare climate conditions, straw is most commonly used within the building industry as insulation.

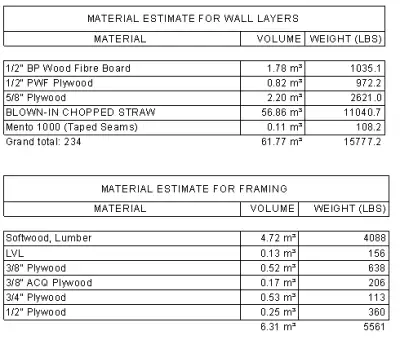

Processing straw for this purpose is straightforward. The baled straw is chopped in a machine known as a tub grinder. There are no chemicals involved in the chopping process. As the name strongly suggests, “chopped straw” is literally just chopped straw. Once chopped, it can then be stored for a few weeks until it is blown into a panel with an off-the-shelf insulation blower. For Savick, the panel is double-stud, plywood construction with high-performance Pro Clima tapes supplied by 475.Supply (see Table 1). Thicknesses can range from 8 inches to 16 inches.

Straw FAQs

Straw is a sturdy, safe, and effective insulating material that has the bonus of sequestering carbon. However, many people have reservations about using it in modern construction, as reflected in some of the more frequently asked questions that Sam encounters. We’ll explore those questions below.

What Is the R-Value of Straw?

It depends.

Straw bales can have R-values ranging from 0.94 to 2.38 per inch. The range is dependent on the density of the straw and the temperature and humidity at the testing site. It can also be affected by how the straw bale is positioned. According to Appendix S of the 2018 International Residential Code, which has had a chapter on straw construction since 2015, straw bale walls with bales laid flat have an R-value of 1.55 per inch of bale thickness, while straw bale walls with bales on-edge have an R-value of 1.85.

For Savick, the R-value is notably higher because the straw is first chopped and then densely packed into a panel. The typical density of straw within a Savick panel is 5.62 lb/ft3 (90 kg/m3). Conservatively, the R-value for the straw in a Savick panel is 3.5 per inch, meaning that one of their 16-inch panels will easily exceed an R-value of 50. For roof construction, a cathedral roof might achieve closer to R-60, whereas a panel with an insulated attic could approach R-100.

Is Straw Going to Rot or Burn?

It depends.

Like wood or virtually any organic material, unprocessed straw that’s exposed to the elements will eventually rot. All biomaterials can also be combustible when exposed to a heat source and oxygen, and straw is no exception.

However, these materials are not just left out in the open. They are components of wall, roof, or foundation systems designed to withstand fire, prevent rot, and promote durability. For Savick, the use of high-performance building methods allows them to create panels that stay dry (below 20% moisture content) and prevent the spread of fire. According to Appendix S of the IRC, straw can have a 1-2 hour fire rating depending on how the straw is protected on exposed surfaces.

So, to answer the question, straw that has been dried, packed into a panel, and wrapped with high-performance membranes, such as SOLITEX MENTO Plus from 475, will not easily rot or burn. It will meet or even exceed any fire resistance requirements.

“Straw is pretty inert,” Sam says. “If you can protect it, it’s not going to be a problem.”

Is Straw a Sturdy Building Material?

It depends.

If you’re looking at straw as a raw material that’s been mixed with clay, no. It is not particularly sturdy. You may be able to able to make a single-story home with a four-foot overhang in a very hot and dry climate like Arizona or Nevada, but that is likely the extent of its utility.

Savick’s straw panels are a bit more robust. “It’s a bunch of rectangles that hold straw in place,” Sam says. “It’s not the weakest building.”

That said, not all straw panels are going to be built the same. Depending on a building’s climate, and more importantly the direction in which moisture is traveling through the wall assembly, modifications to the detailing may have to be made. For example, panels for a project in northern Alberta will be distinct from panels for a project in Seattle, as the latter will have to allow for far more drainage and drying.

Is Straw Right for My Project?

It depends.

Straw panels are versatile and can be assembled to meet the needs of any climate. However, shipping Savick straw panels from Alberta to Australia or Europe is not reasonable. It simply doesn’t make financial sense and is totally out of the question for any project with a carbon budget. It makes far more sense to use local materials, which may include locally grown straw. As a result, Savick panels are most well-suited for homes in North America.

Similarly, building to code minimum in a temperate climate may not be cost-effective. “There’s a lot of fixed costs with the straw panel system that get absorbed pretty quickly on the higher performance end of things,” Sam says. Given how abundant and cheap straw is, the thicker the walls and the higher the volume of insulation, the more cost-effective straw panels become.

Especially for high-performance projects where embodied carbon is a concern and the use of natural buildings materials is given a priority, straw panels can be an ideal and cost-effective solution. There’s a lot of straw around and there’s a growing demand for efficient and high-performance buildings.

“I think the two can be married together,” Sam says. “If you want to learn the how, we want to be a part of that conversation.”