![20230224 073834[1]](

/img/asset/cHVibGljL2FydGljbGVzLzIwMjMwMjI0XzA3MzgzNFsxXS5qcGc/20230224_073834%5B1%5D.jpg?w=960&fit=crop&fm=webp&q=60&filt=0&s=0856172987c2530fb78905e4cabd562d

)

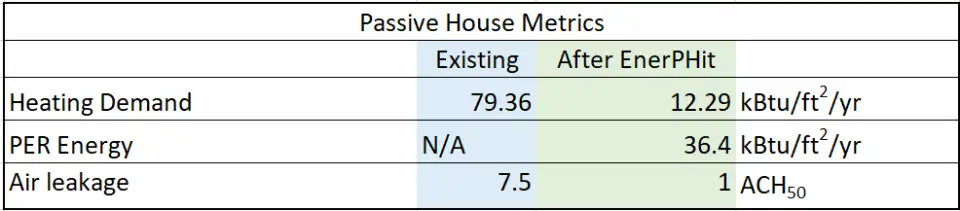

“The very first sledgehammer blow was January 2020,” David Karon of Karon Custom Built says about starting the EnerPHit retrofit of his home. That was the beginning of the hands-on portion of his Passive House journey, his first opportunity to put into practice his tradesperson training. Karon has worked in construction for 20 years in and around Livingston, Montana. For much of that time, he was an independent contractor, learning the ropes and working with general contractors in the area, who tend to rely on independent workers rather than full-time employees. Eventually he became a general contractor himself and in 2017 started Karon Custom Built.

Though Livingston is a modest city of just over 8,000, there is significant demand for custom homes in this part of Montana. The city is only a few miles east of the more affluent Bozeman and a lot of second homes dot the 52-mile stretch of Paradise Valley separating Livingston and Yellowstone National Park. The landscape is truly epic in scale and characterized by extremes, including the weather. Situated in climate zone 6B, the average highs in the summer tend to crest around 100°F, while winters can see weekslong stretches of freezing temperatures and heavy snow.

“The population of homeowners can benefit from a major paradigm shift focusing on the performance of their building envelopes,” Karon says. “From my observations a huge educational gap is evident on the behalf of builders and general contractors specifically. These are the two parties who can greatly influence and direct projects of any size. While renewable energy systems are gaining momentum, a large oversight is the increased awareness of consumption. By making a priority of the building envelope first, it sets up the structure for comfort, durability, and a stone's throw from energy independence."

The Road to Damascus Cuts Through Fort Collins

Karon’s introduction to Passive House sounds like a conversion story. Several years ago, a coworker told him about net-zero building, which he had never heard of at the time. After learning more, he was unimpressed. While he was certainly interested in cutting down emissions, he felt it didn’t do anything about consumption. “It was all just kind of a numbers gimmick of like, offset through renewables, which do also require resources to build and maintain,” he says.

Soon after he found an article about Passive House. “I don’t know, after about a paragraph, I was like, ‘This is what I’ve been looking for as a builder for a long time!’”

It wasn’t long after his discovery of Passive House that he learned about Emu Passive, signed up for a class to become a certified Passive House tradesperson, and was on his way to Colorado to Emu’s facility in Fort Collins. “After four days there, I was like, ‘This is it. This is how everyone should be building anyway.’ It just made sense. I mean, there wasn't one part of it that made me think twice.”

Since going down the Passive House rabbit hole, he’s encouraged clients to build more efficient homes and is currently working on a retrofit project that is pursuing PHI’s Low Energy Building status in Gardiner, which is home to the northern entrance into Yellowstone. He really appreciates rehabilitating older homes, because they’ve stood the test of time and can be converted into better buildings without the need to disrupt more land. Inevitably, this perspective led him to performing a Passive House retrofit of his own home in Livingston—by himself. “I’m the general contractor, the architect, the engineer, the builder, the investor, and the occupant all at once,” he says with a laugh.

Even if these combined roles amount to a herculean task, Karon beams with excitement when he talks about building better and Passive House construction. Still, he acknowledges that it has not been an easy project. On his site, he writes, “The best way to describe the project is by comparing it to open-heart surgery where little anesthetic is used and the patient is awake during the procedure.”

Preparing for Surgery

After returning from Colorado, Karon and Emu’s team engaged in a months-long conversation about energy modeling, determining the window and door packages, and figuring out the sequencing that would allow him to live in the house while performing the retrofit. These services were available because Karon is participating in Emu’s North American Passive House Pilot Program.

According to Emu co-founder Enrico Bonilauri, Emu’s consulting process follows two steps for any project. The first, known as Project Boost, occurs at the schematic design stage of a project and was once known as Preliminary Passive House Review. “We factor in different variables to see how much to insulate or what window packages to use and try to find the sweet spot for the project,” says Bonilauri. Those who are hoping to improve the performance of the project for comfort, indoor air quality, and energy efficiency, and build better than code—but not follow through with certification—will follow the recommendations from Project Boost and stop there.

Bonilauri estimates that 20% of those who participate in Project Boost go on to become part of the more intensive Pilot Program and to certify, while the remaining 80% use the Passive House science to improve the building and inform decisions on performance and budget at an early stage. The 20% who take part in the Pilot Program provide data to Emu and in return receive assistance in navigating the certification process and access to resources that include construction details, specs, reviews of Passive House-related quotes, support during construction, and dedicated pricing from participating manufacturers. As Bonilauri notes, many single-family projects have details that are very similar, and it is not an efficient use of resources to have the architect treat common iterations as unique design challenges. By providing standardized, pre-vetted Passive House details for more familiar features, Emu’s Pilot Program reduces time and costs for modeling, and shifts the focus to supporting the builders during construction.

Ultimately, Emu and Karon determined that certifying under the Passive House Institute’s EnerPHit standard was the most feasible option for the project. PHI created the EnerPHit standard specifically for retrofits. While less rigorous than the traditional Passive House standard, it accounts for immutable factors that can adversely affect the performance of existing buildings such as form factor or orientation, Bonilauri says. Bonilauri also notes that they determined that of the two paths to EnerPHit certification, the component path and the performance path, the former was more practical.

“The component path is almost prescriptive,” Bonilauri says. “Passive House does not have mandated R-values or U-values for certification, whereas EnerPHit by components does.” Moreover, there are no caps on heating and cooling demand when following the component path, but Bonilauri notes that energy modeling using the Passive House Planning Package (PHPP) is still necessary to comply with the primary energy renewable (PER) requirement.

Following the component path has also made certification easier for Karon, as his renovation is being spread out over several years in an incremental process, rather than all at once. Karon notes that there were even options to complete the retrofit over the course of 12 or 15 years had he wanted to only work a few weeks out of the year. However, he’s taken a more aggressive route and hopes to finish in less than half that time. For him, it’s not merely a place to live or a project, but a showpiece for others in the area who have never heard of Passive House construction or an EnerPHit retrofit, and throughout construction he has provided local people with tours of the house whenever he can.

“Whoever built it, I’m really impressed,” Karon says, reflecting on how the original house was almost ideal for EnerPHit certification. It needed minimal changes in terms of site work and orientation. Moreover, it’s remained comfortable throughout construction. Even in the dead of winter, he has managed to heat the home with just two space heaters and a wood stove.

Built in 1957, Karon’s house is a modest bungalow with 1,150 ft2 on the ground floor and the same footprint in the basement, which had been finished even before Karon started the retrofit and contains his two boys’ bedrooms, as well as a guestroom, laundry room, den, and full bathroom. The home sits on a hill oriented almost due south, and along the south-facing wall are three large windows that look directly out to Mount Livingston. It also has a hipped roof with 30-inch eaves that provide a lot of solar shading.

“I definitely got lucky with the house to start,” he says.

![20230224 074016[1]](

/img/asset/cHVibGljLzIwMjMwMjI0XzA3NDAxNlsxXS5qcGc/20230224_074016%5B1%5D.jpg?w=960&fit=crop&fm=webp&q=60&filt=0&s=04b179b97a703b66bf5e3d15030c9d1c

)

Living the EnerPHit Life

Which brings us back to that first sledgehammer blow in 2020. By that time, Karon had solidified the window and door order and received design details and drawings of different sub-assemblies from Emu, as well as Bonilauri’s blessing.

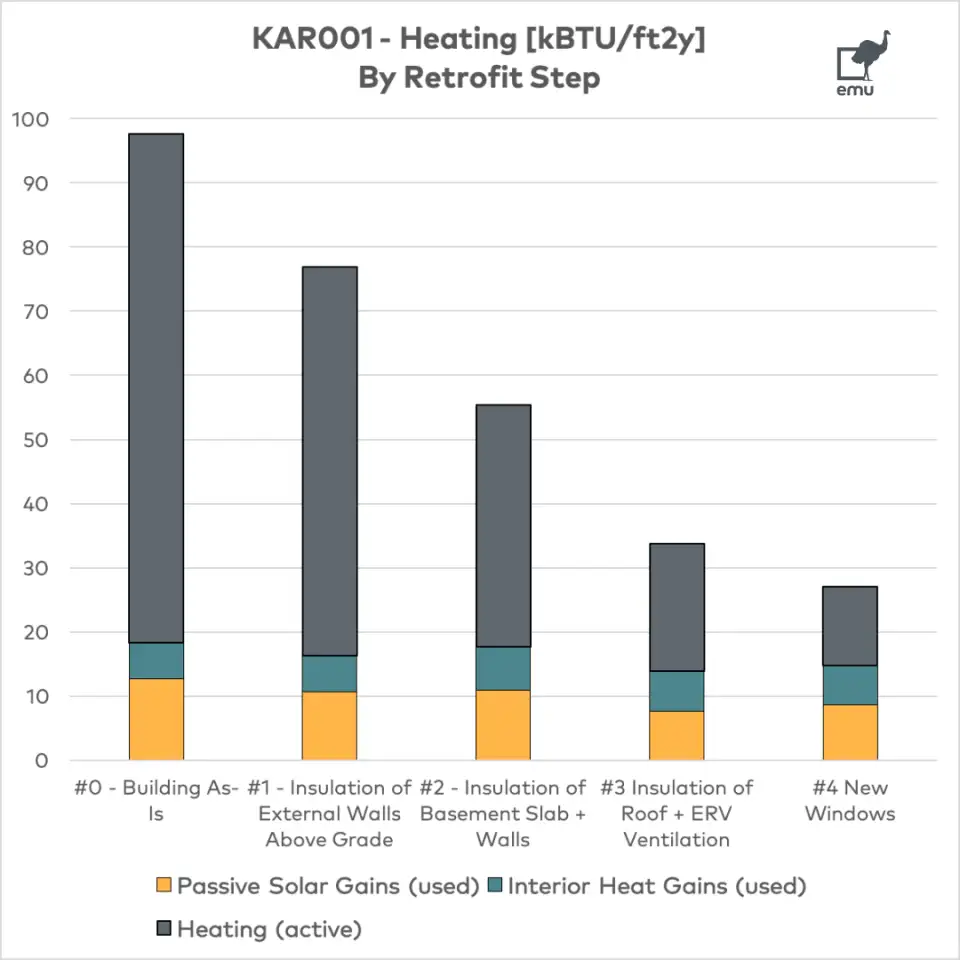

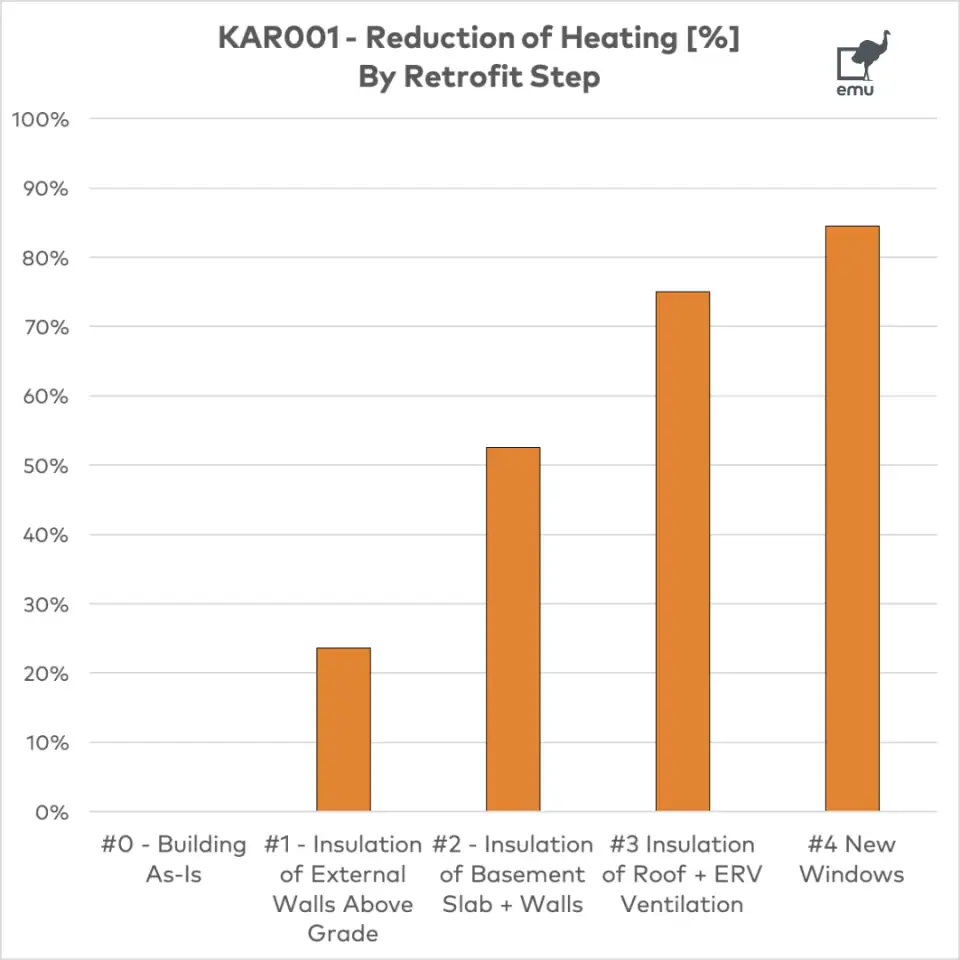

Karon’s sequencing of the retrofit started with the envelope and has largely been tied to the seasons, focusing on above-grade work in the summer months and the basement work in the winter. Very few upgrades had taken place since the home was built, so the idea of removing the entire heating system before sealing up the home was simply off the table. Beyond that, he said that his decision where to work was largely just “builder’s intuition” that he’d developed after a combination of working in construction for so many years and just knowing the house.

“For the first two years, every Friday, Saturday, Sunday, I would attack part of it. And it was just me,” he says. “I've got about 27 hours every week that I can dedicate to the project, and it’s definitely been interesting to see what one person can do in 27 hours and still have time to go to the grocery store and get dinner on the table that night for the kids.” Karon says that he prepares for each weekly phase of the project by relying on a technique that is common among climbers (most notably Alex Honnold of Free Solo fame). He sets a goal for the weekend on Sunday night or Monday morning, and then spends Monday through Thursday working backwards and visualizing what steps are necessary to finish. By the time Friday morning arrives, he has his plan and can spend the next three days executing it.

Karon started in the basement in the spare bedroom, and he wasn't sure what kind of framing he was going to find underneath. “It became a strange obsession. I'd take the kids to school on Fridays and I'd tear off as much sheetrock as I could in the basement while they're at school. They'd come back, and they're like, ‘Where'd that wall go, Dad?’” he recounts with a laugh. “It just was a slow de-evolution. The kids would be missing one more wall, then one more wall.”

“I took away walls and sheetrock as much as I could so that I could attack, you know, several tens of square feet all at once in a day with the floor system to start. And then there was air sealing the interior side of the concrete wall and then getting the required installation and the stud base.” Eventually, what Karon learned was that there were fewer load bearing structures hiding beneath the sheetrock than he expected, which gave him more options for remodeling.

One of the more technical reasons why they decided to follow the component path rather than the performance path was due to the foundation system. The walls of the full basement are eight-inch-thick concrete and sit on a subgrade concrete slab. While energy models indicated that insulation beneath the slab would improve the home’s performance, Karon knew that this was not going to be possible, as the slab is 5½ inches thick. Just opening up a six-foot by four-foot area so that a plumber could upgrade the existing plumbing was almost too arduous of a job. “It makes my hands hurt thinking about it,” Karon says.

Instead, Karon installed an inch of polyiso insulation and an air barrier on top of the slab, and then covered it over with plywood. The basement height from slab to floor joist was 87 inches before the upgrade, and is now 84 inches, but the lost space is barely noticeable, Karon says. What is noticeable is the difference that just an inch of insulation makes when outdoor temperatures drop to -20°F. The perimeter of the floor was sealed with a liquid-applied membrane, and the interior walls have been outfitted with ¾ inch of polyiso and a 2x4 stud bay with Rockwool insulation.

Upstairs, the original wall assembly was 2x4s with batt insulation. To greatly boost the envelope’s airtightness, he has relied on Huber ZIP sheathing and ProClima tapes and liquid membrane for all the nail penetrations and at transitions where tape is not feasible. On the exterior of the ZIP sheathing is a 6-inch layer of Rockwool insulation, a WRB membrane, and a conventional rainscreen system.

As of early 2023, Karon believes he can finish by fall of 2024. At present, he is waiting to put up the siding once the new doors and the new Smartwin windows are installed. Following that, he will also install a Zehnder ComfoAir 350 ERV for the home’s ventilation system and finish taping and air sealing.

Once construction is complete, the heating system will rely on an air-to-water heat pump manufactured by Arctic that will utilize the existing radiators in the house. The glycol mixture from the heat pump will also play a role in his domestic hot water system, as it will be transferred to a small buffer tank roughly the size of a standard water heater. Incoming water then runs through a 1-inch copper coil within the tank and is preheated by the glycol mixture before going to the 20-gallon on-demand tank.

At three years in, Karon is still excited about the project. “It's really tested me as a builder and it's been a really great educational experience,” he says. “It’s a very hands-on experience. You can only read so many books about something. Sometimes you just have to actually do it to really educate yourself.”