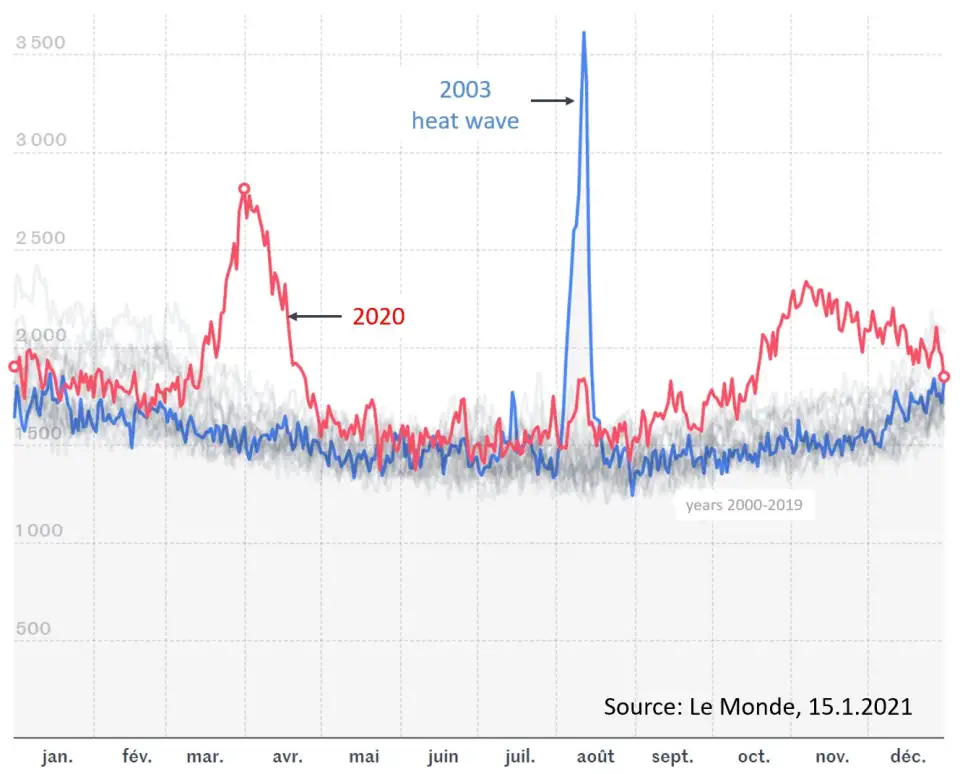

With rising global temperatures and increasingly frequent summer heatwaves, keeping cool in Passive House buildings has become a hot topic. Bad jokes aside, overheating can be deadly; in France the peak mortality rate during the 2003 heat wave was higher than during the first wave of COVID in 2020 (see Figure 1).

Given the realities of our changing climate, active cooling in all climates warmer than warm-temperate has increasingly become standard. For cool-temperature climates, though, the cooling question is not as clear-cut. Is passive cooling sufficient, or is active cooling unavoidable? What are the pros and cons of the different systems? Will my client ring me up during the next heat wave and give me an earful, or worse?

Passive Cooling

Careful design, moderately sized and well shaded openings, close attention to local climate, and active users have been found to be key drivers of successful passive cooling. Reduction of internal heat gains is also critical, including specification of efficient appliances and compact domestic hot water (DHW) systems that avoid the need for recirculation circuits. If recirculation circuits are unavoidable, then so are high levels of pipe insulation and flow rate control, with reduced DHW water supply temperatures—so long as this is compatible with Legionella prevention. Ultrafiltration and chemical shock disinfection are promising alternatives to the conventional solution of high DHW supply temperatures and thermal shock prevention.

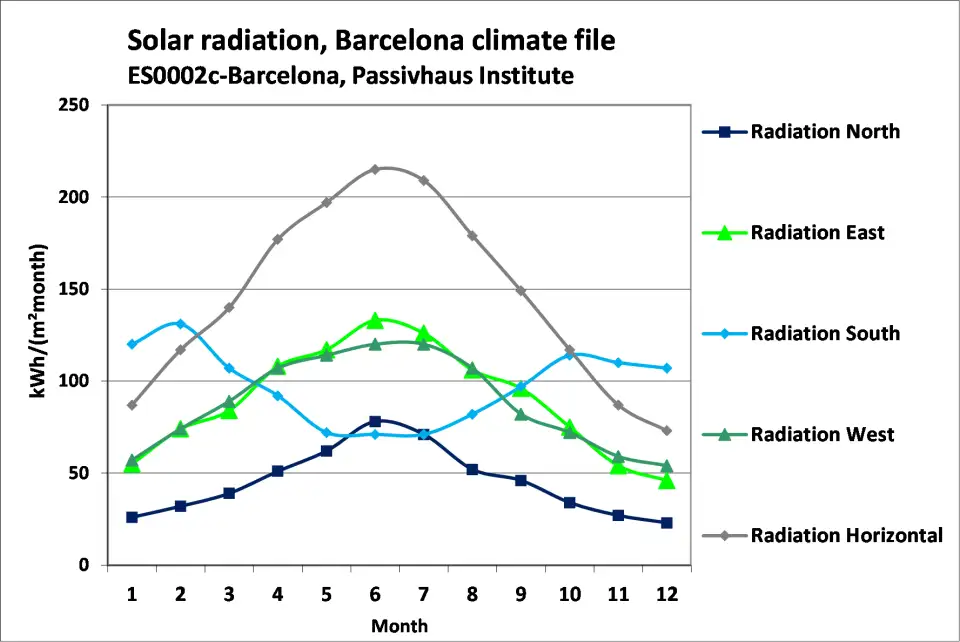

External shading devices are essential, ideally with motorized external blinds that are either user controlled or automated. Even north-facing windows in Passive House buildings need shading, because the very long time constant of Passive House buildings mean diffuse solar radiation can cause overheating. If only fixed shading can be used, then appropriate solutions for each orientation are key, with particular attention to east- and west-facing glazing, which receive more solar radiation in the summer than south-facing glazing (see Figure 2). Deep horizontal overhangs on southern glazing work best (or northern glazing in the southern hemisphere), with slanted vertical fins for east- and west-facing glazing.

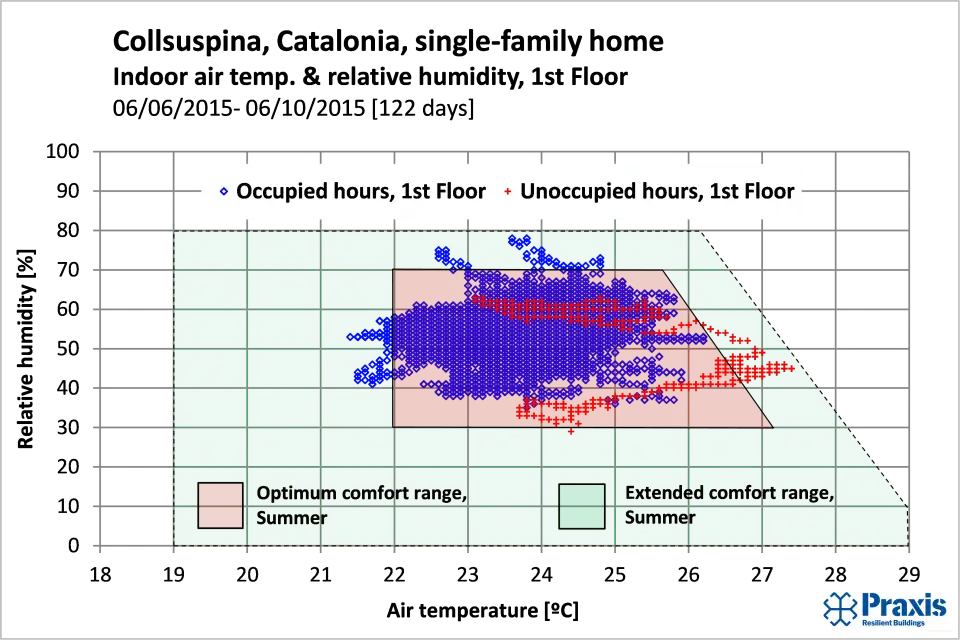

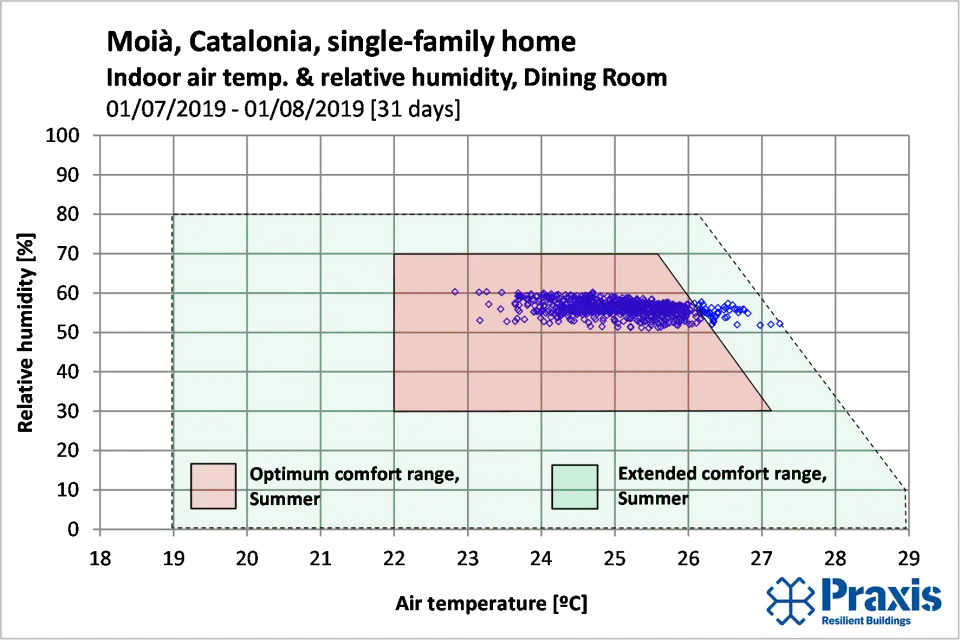

Natural night ventilation combined with thermal inertia works well when night temperatures are sufficiently low. Cool external colors, high levels of insulation in roof assemblies, ground coupling, and ceiling fans are also effective strategies. Figure 3 shows an example of measured data for a single-family home (but one with little thermal inertia) employing many of those strategies.

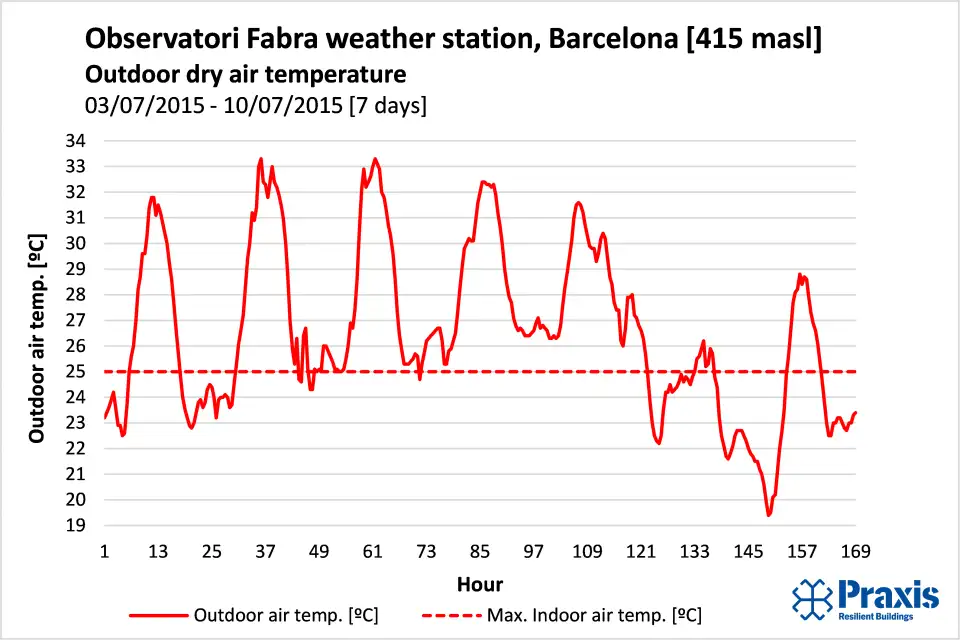

Passive cooling can deliver good performance under the right circumstances and has many advantages; it is in general simple, low cost, and easy to install, maintain, and commission. However, passive cooling strategies are highly climate dependent and rely on careful user behavior. Where average air temperatures and levels of solar radiation are high (leading to a hot ground), minimum night temperatures do not drop below about 20 ºC—limiting cooling power from natural night ventilation—and night sky temperatures and outdoor air humidity are high, passive cooling won’t maintain indoor comfort. In such cases, active cooling is unavoidable. Figures 4 and 5 show an example of climate conditions in which passive cooling strategies won’t work, during the 2015 heat wave in Barcelona, Spain.

Active Cooling

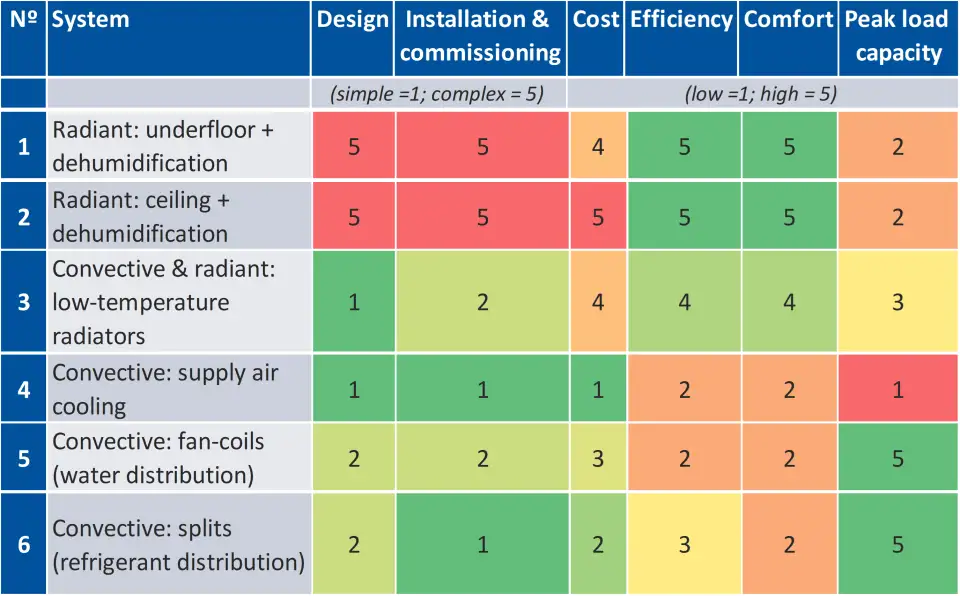

I compared six different cooling systems that had been designed and installed in residential Passive Houses in Spain, assessing six criteria through a simple 1-to-5 point scoring system (see Table 1). Monitored data are provided for systems 1, 2, 5, and 6. What follows are my experiences with each of the system types.

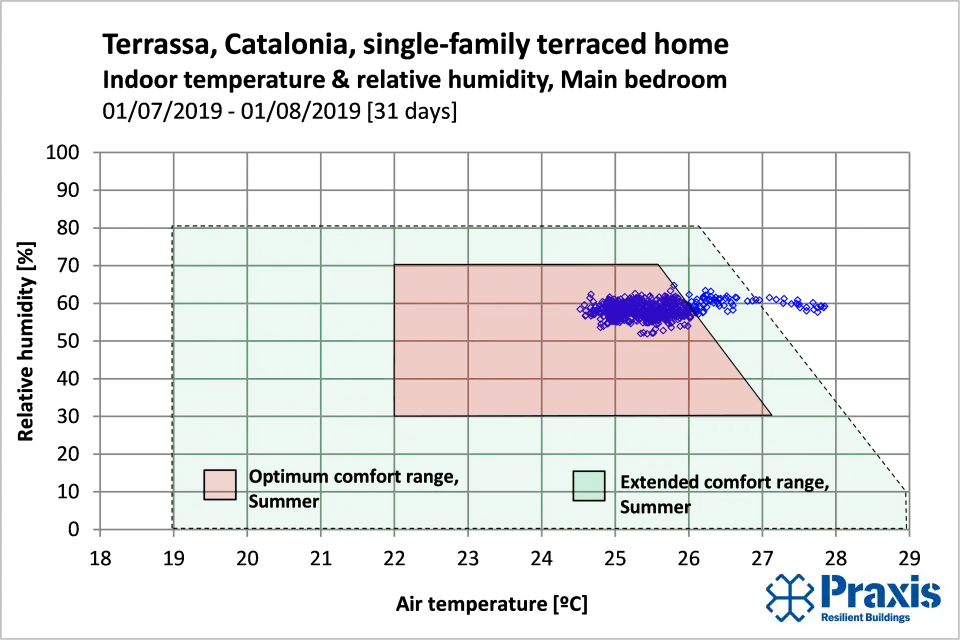

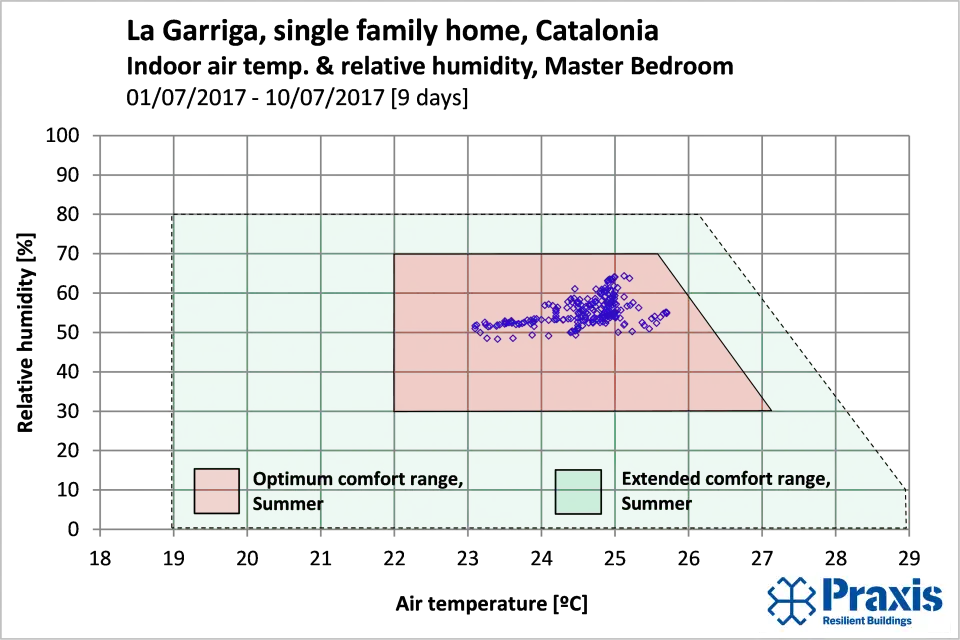

Radiant cooling systems offer a high level of comfort and efficiency, but are more complex to design, install, and commission, and have a high capital cost. Humidity control and cooling power have been found to be problematic in warm and humid climates, particularly in houses where users regularly go in and out to access such features as gardens or balconies. Monitored data for an underfloor cooling system is shown in Figure 6. Figure 7 shows monitored data for a radiant ceiling system.

![Figura 06.2 Terrassa [Source RGA Arquitectes]](

/img/asset/cHVibGljL0ZpZ3VyYS0wNi4yLS0tVGVycmFzc2EtW1NvdXJjZS1SR0EtQXJxdWl0ZWN0ZXNdLnBuZw/Figura-06.2---Terrassa-%5BSource-RGA-Arquitectes%5D.png?w=960&fit=crop&fm=webp&q=60&filt=0&s=bdefd6cc1d1108bdc31082783d3e495d

)

Low-temperature radiators—set in the floor or wall-mounted—offer a reasonable balance between simplicity, cost, efficiency, and comfort, albeit with less cooling power than fan-coils and splits. A greater number of individual radiator units are required to condition the same area that a ducted fan-coil/split system would service, as one such indoor unit can cool several rooms. Figure 8 shows monitored data for this kind of system.

Supply air cooling, which conditions outdoor air at low flow rates rather than recirculating indoor air, can deliver only limited cooling power. Heat gain along the generally long duct runs contribute to this system’s limitations. Power can be increased using partial recirculation, but the monitored data in Figure 9 show that temperature and relative humidity often move outside the extended comfort range. The advantages of this kind of system are simplicity and low capital cost, but the limited cooling power means passive cooling measures must be robust; once overheating has set in, the system will struggle to eliminate heat.

Conventional convective solutions that cool recirculated indoor air—such as ducted or wall-mounted fan-coil or split systems—have been found to be the most robust. They have a lower capital cost than radiant systems and are generally simple to design, install, and commission. Another advantage is their power can be modulated to deal with peak loads, although for many people they can be less comfortable than radiant systems. Split systems using refrigerant distribution offer greater dehumidification power (due to lower refrigerant sink temperatures than water) with a faster response than fan coils and water distribution. However, the global warming potential (GWP) of the refrigerants and the risk of leaks from on-site manipulation are important considerations. Figure 10 shows monitored data for a ducted split system. Temperatures outside the extended comfort range are during hours when the home was not occupied, and the clients report a high level of thermal comfort.

[Figure 1 source] Jonathan Parienté, Pierre Breteau, Maxime Ferrer, 2021: Covid-19 : davantage de morts au printemps 2020 que lors de la canicule de 2003. Published 18 September 2020 in Le Monde.