I'm trained in engineering and have worked either developing or selling test and measurement (T&M) equipment for the last 30 years. Not just any T&M products—only those associated with building performance and heating, ventilation, air-conditioning, and refrigeration equipment produced by such fine companies as Bacharach and Testo. Throughout this whole time, and only until very recently, all indoor air quality (IAQ) meant to the broader market was monitoring temperature and humidity, and in a few cases CO2. A wave of new air quality measurement devices available at increasingly lower price points has more and more people testing. What is the value or purpose of these products in a high-performance or Passive House building?

A Healthy Home

Nate Adams, home performance professional and author of The Home Comfort Book, describes a healthy home this way:

A healthy home is in balance. It’s comfortable, healthy, and easy to control. Part of what makes it healthy are that moisture levels aren’t too high or too low, dust particles are being filtered out, chemical and pollutant levels are under control, and the air just feels fresh. In other words, indoor air quality (IAQ) is continuously managed all year.

A decade ago, personal health monitoring was mostly limited to the bathroom scale. Now millions of people closely monitor their Fitbits, weather data, steps taken, visitors, and stock market and Twitter feeds from their watches, doorbell video cameras, and smartphones. Soon the Apple Watch will allow something that approximates a real-time EKG. Personal health is on the public’s mind. Now more than ever, health-related information (of varying quality) can be seen in social media posts. It’s easy to “research” and self-diagnose on the Web.

“We’re on the cusp of a trend,” Nate Adams says. “Homes are gaining more and more sensors like cars did a decade ago. People are looking for their houses and systems to talk to them. The IAQ sensors are the first bridge.”

We breathe about 3,000 gallons of air per day, and many of us spend 90% of our time indoors. We “eat” a lot of air. Sensitive populations, like the elderly and infirm, may spend 100% of their time indoors. Children eat even more air—about 40% more air per pound of body weight than adults.

An Unhealthy Home

IAQ can vary widely, because it is largely related to occupant behavior. Using chemical cleaners, hobby materials and solvents, personal beauty items, and other vapor-emitting products can contribute to poor IAQ. Recent studies underscore that cooking is a major contributor to poor IAQ, irrespective of the type of cooking appliance, since the majority of the emissions come from the food.

It is generally recognized that smoking and burning incense increases particulate and volatile organic compound (VOC) levels. Showering, clothes washing, and bathing increase humidity levels, which can lead to mold growth. All the creature comforts we have become used to can contribute to poor air quality. Vented and unvented combustion appliances, and electric appliances with dirty coils can all produce unhealthy particulate levels.

Many people have systems in their homes to filter the air, but filter replacements are often neglected. We also see installed exhaust systems that are not used, are improperly installed, or operate ineffectively, sometimes merely due to lack of maintenance. People are reluctant to use noisy range hoods, and often these do a poor job capturing what they should.

Seasons change, the weather changes, the humidity and temperature change, even the amount of moisture in the soil changes (affecting radon propagation into a structure). Occupant behavior changes. Equipment breaks down. These constantly changing factors make the case for constant, albeit imperfect, measurements.

Finally, there’s the shell game: If the enclosure is leaky, the nasties get in from the attic, the basement, the crawl space, or outside. If the enclosure is robust, but ventilation and filtration are weak, indoor air pollutants accumulate.

With all these competing factors at play, how do we get to Nate’s Zen condition of balance?

Measuring IAQ

Earlier in my career, I believed that the perfect measurement, taken with expensive test gear, was the only measurement worth taking. Time and experience have softened me on that stance for two reasons. First, it’s beneficial to get users measuring IAQ parameters, even if they are not exact. Second, there are benefits to taking measurements over an extended period of time. A monitor that can constantly analyze and provide feedback helps increase awareness of these changing IAQ factors.

Fortunately, there are now inexpensive monitoring products of reasonable quality that can be broadly installed and remain in place for long periods. In this way, they are like security cameras with motion detection (I recently bought such a camera for $29)—always monitoring the environs and reporting on out-of-character values. Timely reporting can help occupants modify their behavior in real time or command active ventilation or filtration equipment to kick into gear. In many cases, these devices can increase occupants’ curiosity on the topic, leading to better measurements as they come to understand more about their air quality.

Figure 1 shows six low-cost monitors. From left to right, they are (1) LL6070 low-level carbon monoxide (CO) alarm; (2) PG-2017 low-level CO alarm; (3) Corentium home radon monitor with display; (4) Wave Bluetooth radon, temperature, and humidity monitor; (5) uHoo WiFi IAQ monitor with nine parameters—temperature, humidity, VOCs, particulates, CO2, CO, nitrogen dioxide, ozone, and barometric pressure; and (6) Fooboot WiFi IAQ monitor with four parameters—temperature, humidity, VOCs, and particulates. Prices range from $99 to over $300.

Independent lab testing shows that devices like the Fooboot ($199) correlate reasonably well to more-scientific monitors, especially in the particulate values. The uHoo ($329) measures CO2, a surrogate indication of air freshness and a pollutant in its own right, as well as barometric pressure, and noise in decibels. Presently Airthings Wave ($199) and Corentium ($179) are the only devices that provide radon measurements. More-precise CO measurements come from the Defender LL6070 ($160) and CO EXPERTS PG 2027 ($189) alarms with displays.

Most of these devices are app based and Cloud connected, so notifications are available whether you are present or not. Data are logged and plotted with consumer-friendly graphics as well as engineering-type reports and tables. Trend tracking of multiple values can often unravel the complexities of a situation.

Several models send automatic reports and alerts that warn of changing values in real time. This capability allows for event tagging of what the occupants were doing or sensing or feeling at that time, to help understand how their behaviors relate to and impact air quality. Some apps even provide general recommendations on what an occupant can do to alleviate these out-of-bounds values.

Quality

Researchers from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) note that these sensors and monitors are unregulated, and there is limited third-party evaluation information. While they caution people on using these monitors and assuming that the measurements are accurate and the advice relevant, they are also working to make that a reality.

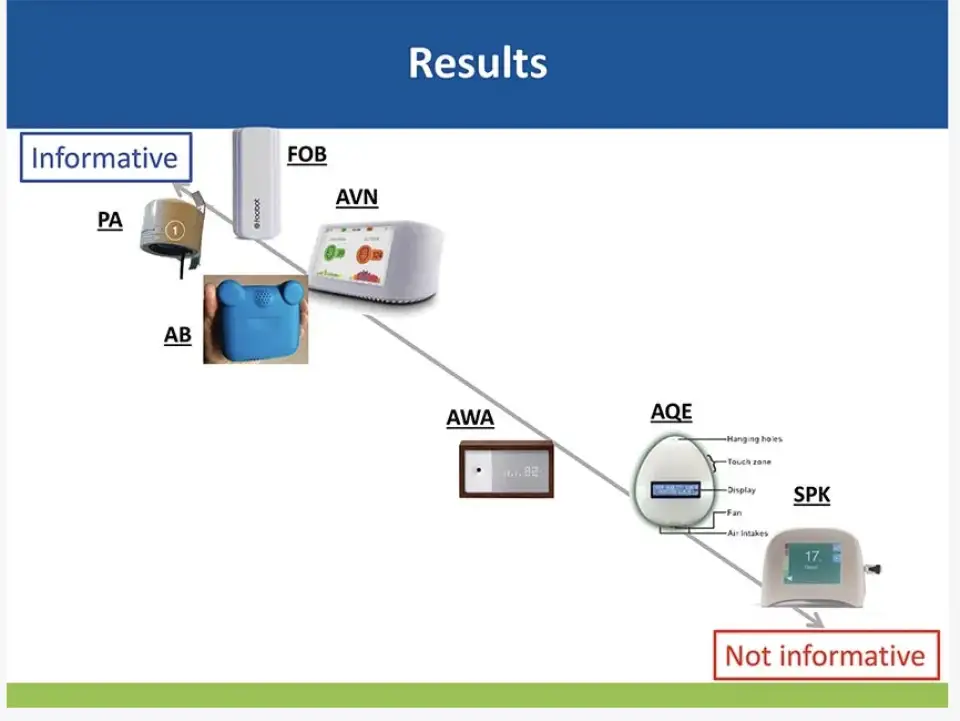

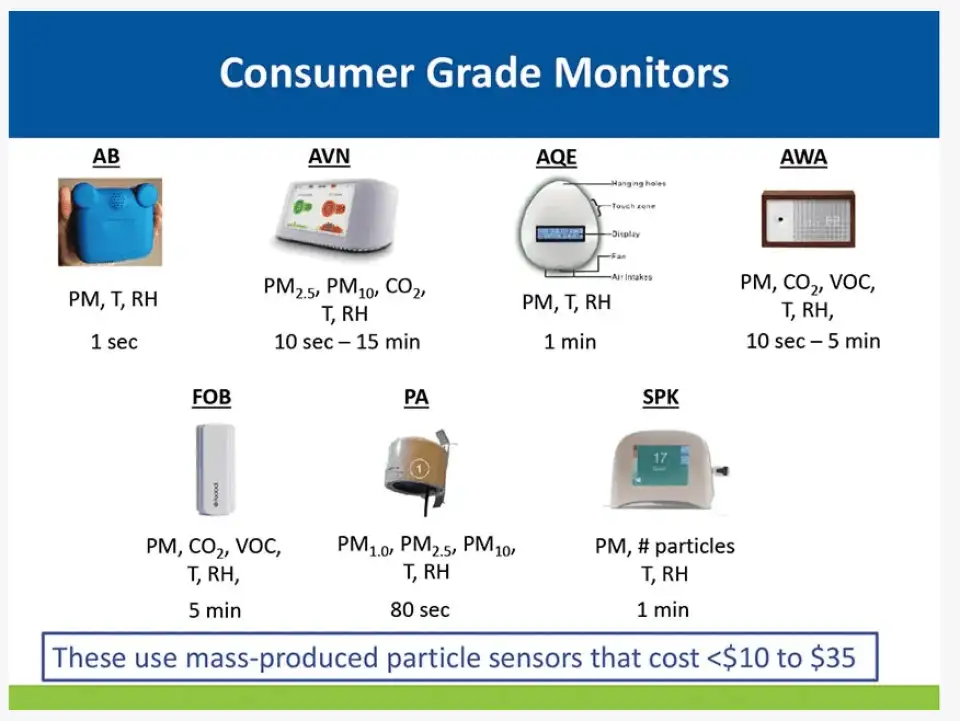

While sensors are getting better, it is important to remember that reliability is not necessarily robust; some units measure certain, but not all, parameters accurately. Figures 2 and 3 show the results of an LBNL evaluation of several low-cost consumer-grade monitors, titled “Consumer IAQ Monitor Responses to Residential Sources of Fine Particulate Matter."

As this evaluation shows, some devices indicate IAQ issues related to particles, but none of them senses ultrafine particles, many which have serious health implications. The researchers feel that although these devices are getting better, there are no devices that are good enough to control a filtration system. There is also a lack of long-term performance evaluation.

LBNL researchers also believe that total VOC readings are almost useless, due to false positives from activities such as drinking alcohol or peeling oranges, for instance. However, the inexpensive CO2 sensors are acceptable, especially when used with drift correction software that functions by assuming that sometime in the past few days there was a “fresh-air incident.” This correction can be error prone when installed in homes where people rarely leave the premises, such as households with the elderly, home offices, or preschool-age children.

There are strong signals that a market for low-cost IAQ-monitoring devices is growing. The Building Performance Institute has developed the Healthy Home Evaluator trade certification for professionals. Bill Hayward, founder and owner of Hayward Lumber, has developed the Hayward Score, a national consumer scoring test for self-evaluation of aspects of a healthy home, along with advice on how to improve one’s own home, or how to connect with contractors.

In conclusion, I believe there is good value for these products with prudent use, especially in high-performance and Passive House buildings.