[Editor’s Note: This article was originally published as part of the 2019 NAPHN Policy Resource Guide, release at its 2019 conference. Registration for this year’s NAPHN conference, PASSIVE HOUSE 2020, opens March 2.]

New York City’s recently adopted climate change bill was initiated by Costas Constantinides, a member of the City Council from Queens, in 2017 as Int. No. 1745–2017. It was modified through the approval process and morphed into Int. No. 1253–2018, until it was approved by the City Council on April 18th and signed into law by New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio on Earth Day, April 22nd, 2019, as the “Climate Mobilization Act.” Its goal was to address the fact that a high proportion of New York City’s emissions come from our existing building stock—emissions that would need to be cut to meet the Mayor’s goal of 80% reductions in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050. At the first City Council hearing that Mr. Constantinides chaired, he spoke about this bill being born out of urgency, with the Trump-led White House pretending that climate change doesn’t exist and rolling back environmental progress and sustainable energy agendas.

The first iteration of the bill (Int. No. 1745–2017) required energy use intensities (EUI) of buildings to decrease incrementally from now to the year 2050. The energy use of buildings larger than 25,000 square feet, as well as of city-owned buildings, would have to be reported, with penalties levied for exceeding certain levels. A study by Urban Green called Blueprint for Efficiency was conducted with input from various stakeholders as to the best metric to use and a list of recommendations was provided.

In 2018 an update of the bill was reintroduced, this time as Int. No. 1253–2018. On December 5, 2018 another City Council hearing was conducted and instead of EUI the metric to be used was carbon emissions. Costas Constantinides announced that the bill had 29 supporting NYC council members, enough to guarantee passage.

Since that second hearing, changes were made to reflect industry input. It was noted that categorizing buildings by occupancy type would not guarantee that comparisons would be apples to apples. For example, a school that operates from 8am-4pm should not be compared to a school that operates from 8–10pm, which will have greater energy use and hence emissions. As a result, the adopted version of the bill now allows the EPA’s Portfolio Manager to be used as a guide to convert to an equivalent use and occupancy group as this takes intensity of usage into account.

One of the groundbreaking aspects of this bill is its far-reaching goal. Instead of owners having to meet ever-changing energy requirements that are updated every few years with every code cycle, this bill sets a clear target and lays out a pathway to get there. British Columbia’s recently enacted step code is similar in that it sets performance-based targets instead of prescriptive ones.

A few more important things to note on Int. No. 1253:

This isn’t the first climate-related emissions bill issued by a North American city. Vancouver, British Columbia, has enacted legislation encouraging owners to build to high performance standards by providing incentives, such as additional floor area.

Unless industry feels it has a pathway forward, the changes required by this bill won’t happen. Given the large number of buildings that will require work, industry members and trade groups have suggested financing incentives to educate owners and help them understand how they can prepare their buildings to meet these requirements. It is vitally important to have these incentives and support in place to help transition owners, industry, professionals and tradespeople. As an example, NYSERDA has recently enacted the Buildings of Excellence Competition, with significant monetary awards to design buildings that perform well above energy code requirements.

In addition to reducing carbon emissions, this bill will greatly increase green jobs in New York City and will spur innovation in the marketplace.

Even though this bill is aimed at existing buildings, the year after a new building is built it will be subject to the requirement to report emissions and to potential penalties if over the limits. These requirements will act as drivers to spur developers to create new Passive house buildings that exceed 2050 requirements!

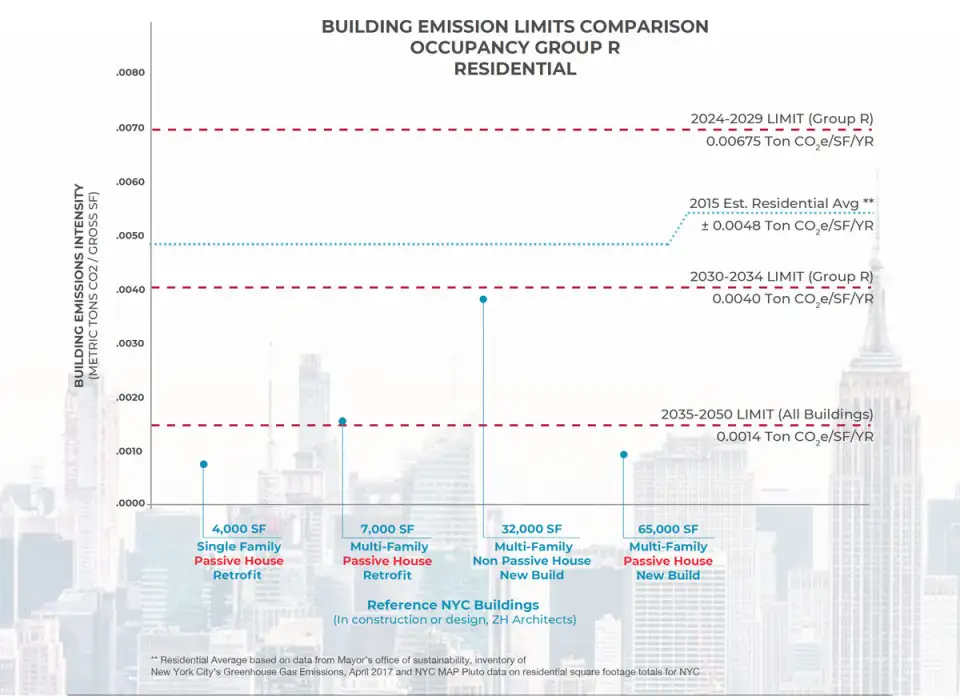

The 2050 emissions targets are not only achievable for new buildings but are also possible when retrofitting existing buildings. The attached chart shows emissions from a number of projects underway at ZH Architects including new buildings and retrofits. All can meet the 2050 requirements and can exceed them easily with additional renewable PV, if needed.

NYC City Council approved Int. No. 1253–2018 on Thursday April 18th, 2019, with 38 out of 51 council members voting for it. With great fanfare, the Mayor of NYC, Bill de Blasio, signed it into law on Earth Day–April 22nd, 2019—as the “Climate Mobilization Act.”

This supports a conclusion that carbon emissions bills, such as New York City’s Climate Mobilization Act, may be used to work hand-in-hand with existing energy codes to require owners to make better buildings. This leapfrogging to performance-based targets is what is needed to meet New York City’s climate change goals and make a better, more comfortable and energy-efficient future for our city and its residents.