Cartagena, Colombia, a UNESCO world heritage site, suffers from a severe shortage of housing. Indeed, in 2014 the government estimated that there was a deficit of 47,328 housing units in the Cartagena area, 36% of which were needed for middle-income folks. This deficit prompted a group of investors and developers to acquire a 40-acre parcel located 7 km (4.5 miles) from the heart of Cartagena’s colonial walled city, with the purpose of developing an integrated urban community. The planned Puerto Madero development includes single-family housing and multifamily buildings of up to 6 stories high and 48 apartments per building, following local density regulations. Municipal permits have been obtained, and the drinking water and electricity supply infrastructure has been developed, for a potential total capacity of 1,700 residential units.

Simultaneous with this need for more housing is the worldwide growing demand for cooling. As stated in the 2018 International Energy Agency report, The Future of Cooling, “Global energy demand from air conditioners is expected to triple by 2050, requiring new electricity capacity equivalent to the combined electricity capacity of the United States, the European Union, and Japan today… The global stock of air conditioners in buildings will grow to 5.6 billion by 2050, up from 1.6 billion today—which amounts to 10 new ACs [air conditioners] sold every second for the next 30 years…” To avoid exacerbating the climate crisis, it is crucial to address the cooling loads of buildings, especially in tropical regions of the world, where cooling and dehumidification is required 24/7.

Lowering the development’s cooling loads with the implementation of the Passive House standard has been a key goal from Puerto Madero’s inception. One of the U.S. investors, Andrew Straus of Consinfra, a private investment fund dedicated to real estate development in Colombia, is a CPHC professional. Having delivered a series of presentations about the Passive House standard, Straus convinced the other investors and developers to set that as the performance target. Subsequently, I was brought on board as a CPHC. Phius has designated the project as a “feasibility project”, because it likely will fall short of certification due to the lack of available raters in the area.

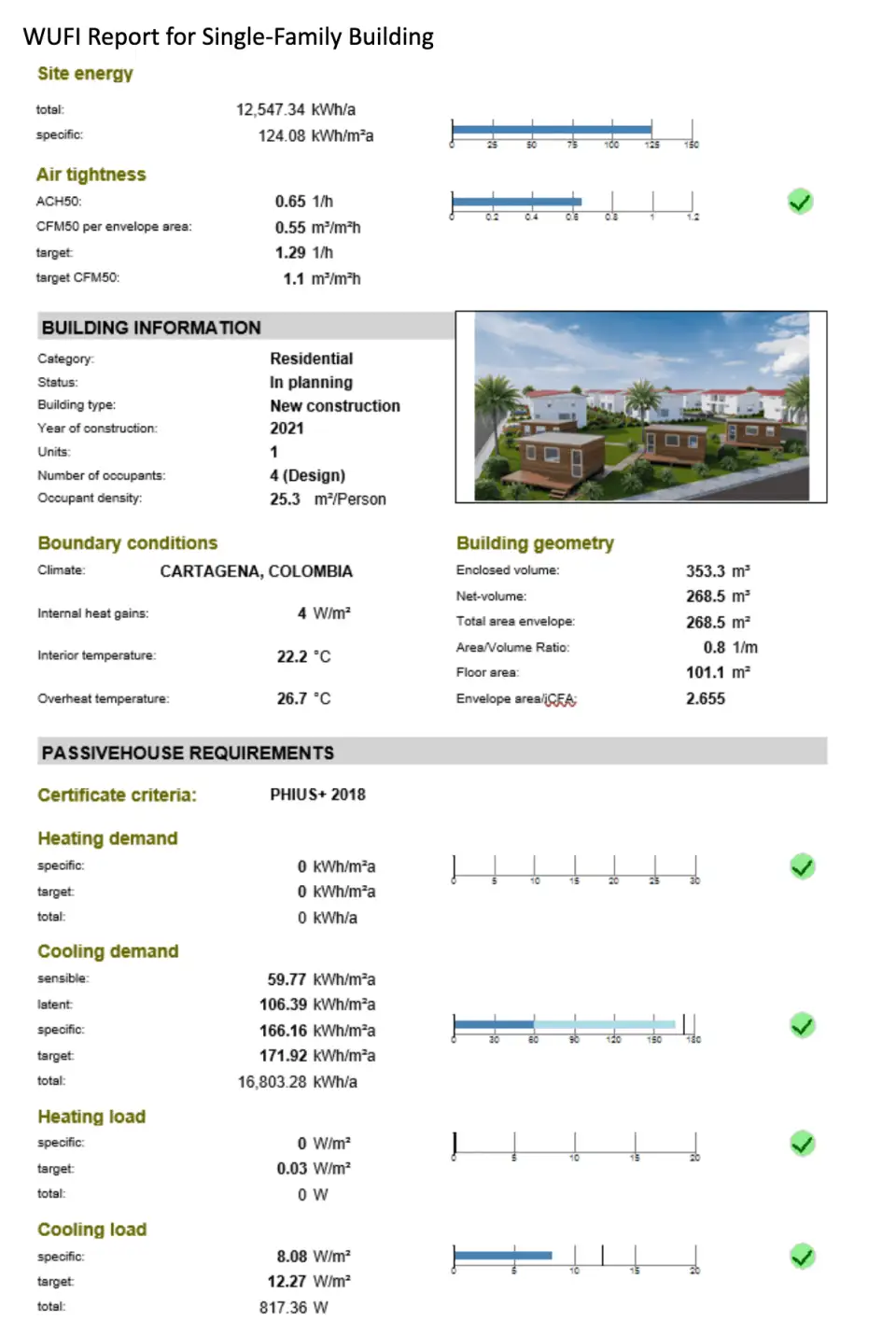

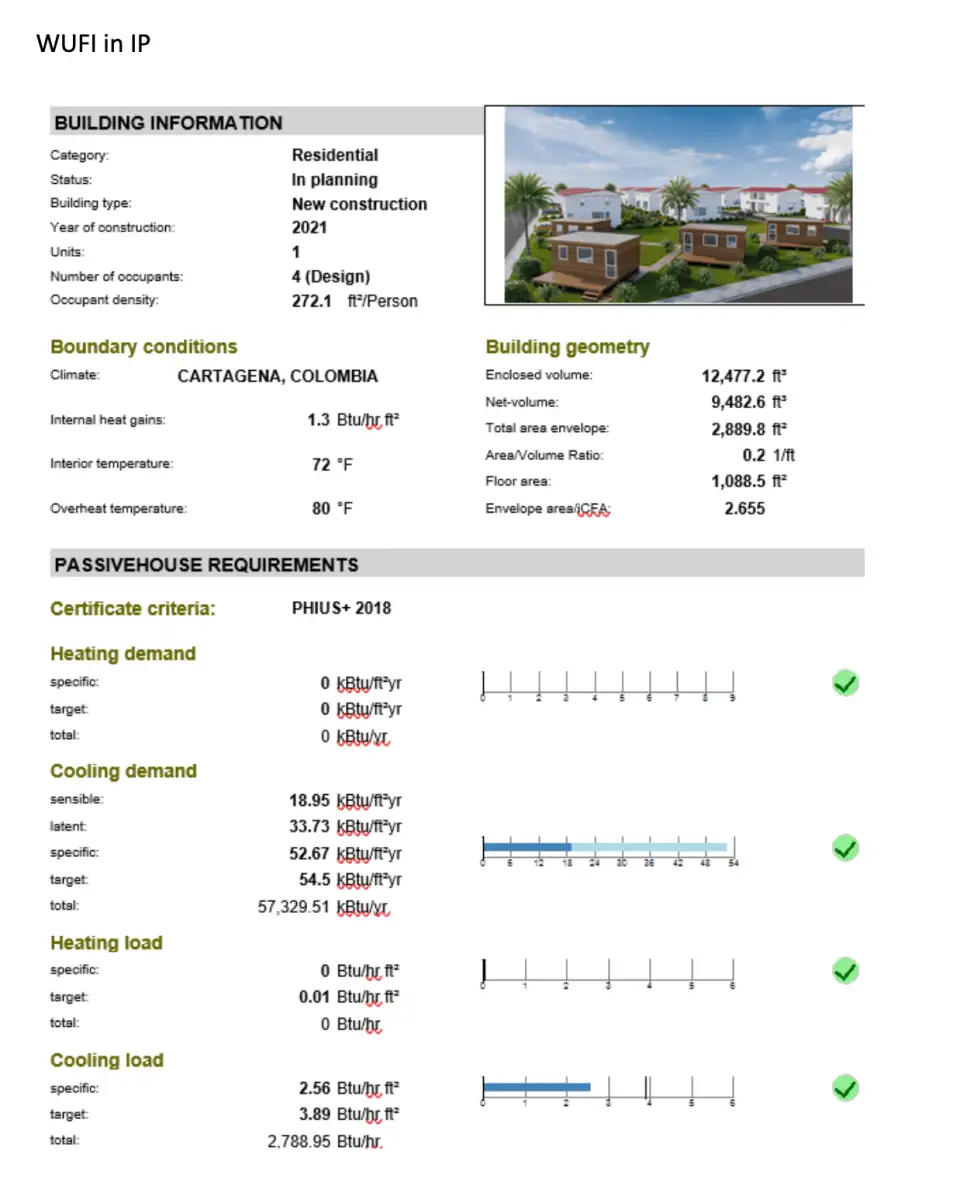

The area’s climate conditions are indeed very hot and humid, presenting the main challenge for the passive design of these buildings, which require only cooling (see Table 1). While the temperature fluctuation through the year is minimal, the consistently elevated dew points—a factor that is prevalent in the tropics—set the stage for comfort, energy use, and durability issues when not addressed appropriately. In most buildings there, occupants use air conditioning systems that are way oversized to compensate for the indoor humidity brought in by natural ventilation practices, causing a great deal of energy waste and setting the stage for cold surfaces that induce mold formation. We are determined that Puerto Madero will set an example of comfortable, healthy housing whose cooling needs are met by small, efficient systems.

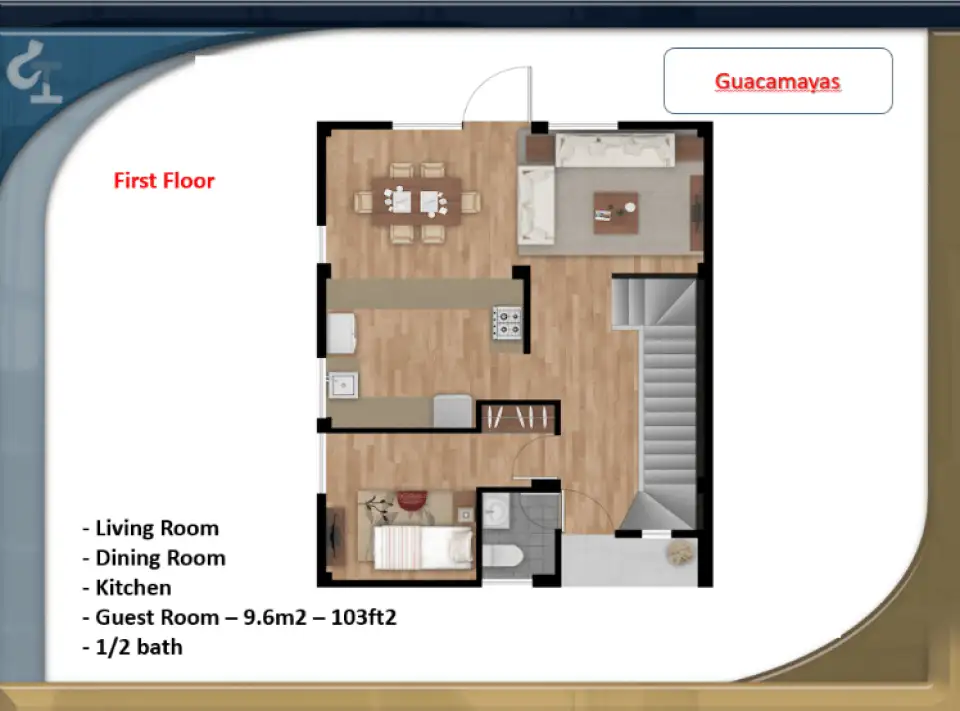

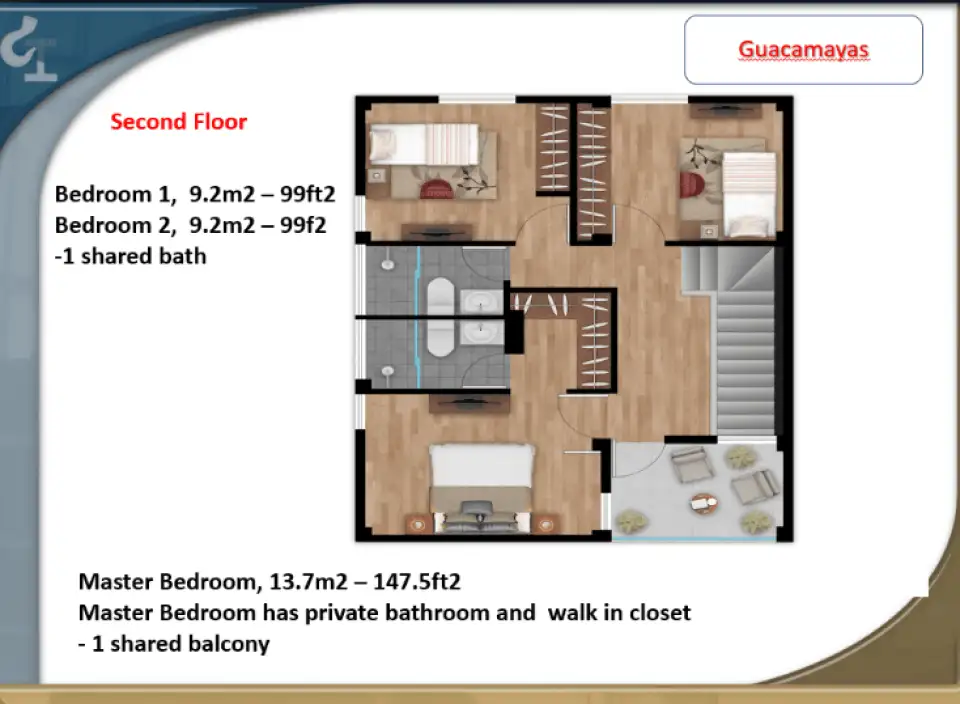

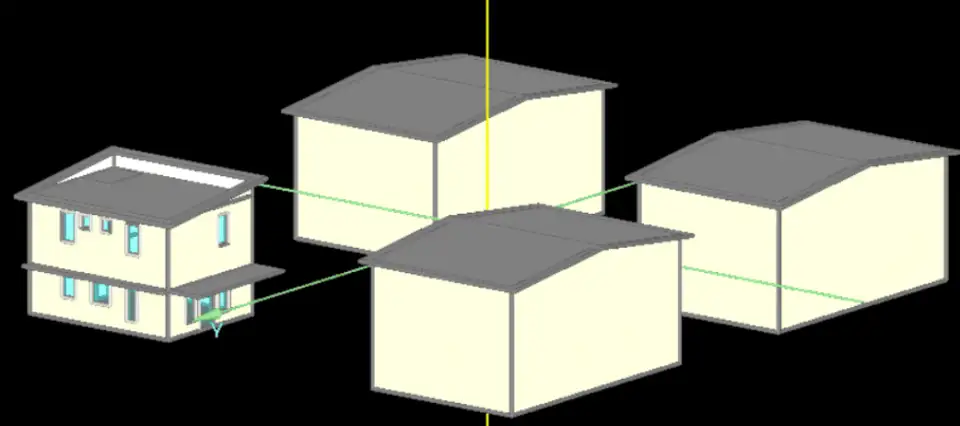

Construction has now begun on Puerto Madero’s first phase, consisting of 27 single-family town houses, in a subsection named Guacamayas (see Figure 1). The first quarter of 2023 will see the groundbreaking for three of the 6-story, 48-unit apartment buildings. Thanks to our early involvement, the development was planned so that the orientation of the lots was optimized to minimize solar exposure. A sewage water treatment plant has been built to support the initial 27 single-family units with a projected expansion planned to cover the needs of the total development. While the permits were being processed and the infrastructure was being built, we worked on creating two WUFI models—one for the single-family homes and another for the multifamily buildings.

Guacamayas Single-Family Homes

As mentioned previously, the lot layout restricted the orientation options for the houses in order to reduce solar exposure, and yet managing solar gain is still a very important consideration in this locale. For the WUFI Passive analysis we chose to begin with the first unit to be built, which presents the largest glazing surface to the west and, therefore, the greatest solar gain challenge. A layout of the houses’ two floors can be seen in Figures 4 and 5.

Solar exposure to the west is difficult, if not impossible, to shade unless expensive exterior shades are used, which in this project are financially out of the question. The budgetary pressures on this project were extensive, as these homes will be competing with those built using traditional construction approaches that do not include insulation, air tightness, adequate windows, nor energy recovery ventilation systems—all incremental costs from the marketing feasibility standpoint.

Realistically, the construction approach had to align with local practices, which are based on reinforced concrete post-and-beam structures that complicate adhering to the principle of continuous external insulation (see Figures 6 and 7). The local practice to alleviate the structural weight is to build the internal walls out of a 100-mm (4-inch) EPS board (R-13 hr-ft2-F/BTU ; R-2.35 m2K/W) lined with a metal mesh to support a stucco finishing (see Figure 8). Therefore, the same practice is being used here to cover the post-and-beam structure and eliminate thermal bridges. The first-floor exterior wall will rest on the EPS slab skirt to provide continuous insulation.

For the ceiling insulation 300 mm (12 inches) of loose-blown cellulose (R-48.5 hr-ft2-F/BTU ; R-8.5 m2K/W) will be used, with an Intello Plus membrane underneath the cellulose. The wall-to-roof junction will have enough of a heel to allow the total cellulose depth to eliminate a potential thermal bridge there.

All wall-to-floor joints will be sealed with a water-soluble polymer emulsion. The foundation will have a 100-mm (4-inch) EPS board, ample insulation here as the ground temperature was found to be 270C (810F) (see Figures 9 and 10).

For ventilation, an ERV was considered, but an ERV alone would not be able to handle the latent load without a DX Coil accessory, and such an arrangement does not exist in the Americas’ market for small ERVs. The sensible loads and partial dehumidification could be handled by a cooling-only mini-split, but still additional dehumidification would be required. A dehumidification unit was considered in the package, but this arrangement would make the solution more complicated, with three different machines, supplied and serviced by three different manufacturers. So, we found a solution in the all-in-one Minotair that could provide dehumidified, cooled, and filtered ventilation air, coupled with a cooling-only mini-split for additional sensible cooling.

Shading is the main tool in hot and humid climate to control energy waste. Trees were considered, but they would have had to grow for many years to attain the required tree height and canopy, during which time the homes’ occupants would have to endure years of exposure and discomfort. Therefore, a 2-meter (6.5-foot) pergola over the first-floor living and dining room windows was the most feasible solution (see Figure 11). This element provides a reduction of 3.24 kWh/m2a (1.03 kBTU/ft2yr) in cooling demand, saving 373 kWh/year or roughly US$60/year. Additionally, a second west window in one of the bedrooms was eliminated from the design.

Because people in the tropics are used to higher ambient temperatures, we set an indoor design temperature of 22oC (72oF) as an adaptive mode, which saves energy compared to a 20oC (68oF) design temperature. We are also targeting an airtightness of 0.03 cfm/ft2 of exterior surface (6 sides) compared to the 0.06 required by Phius.

Six-Story Multifamily Buildings

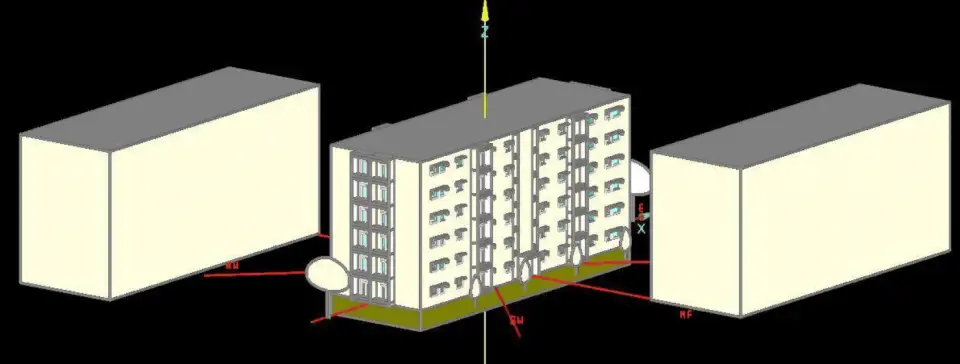

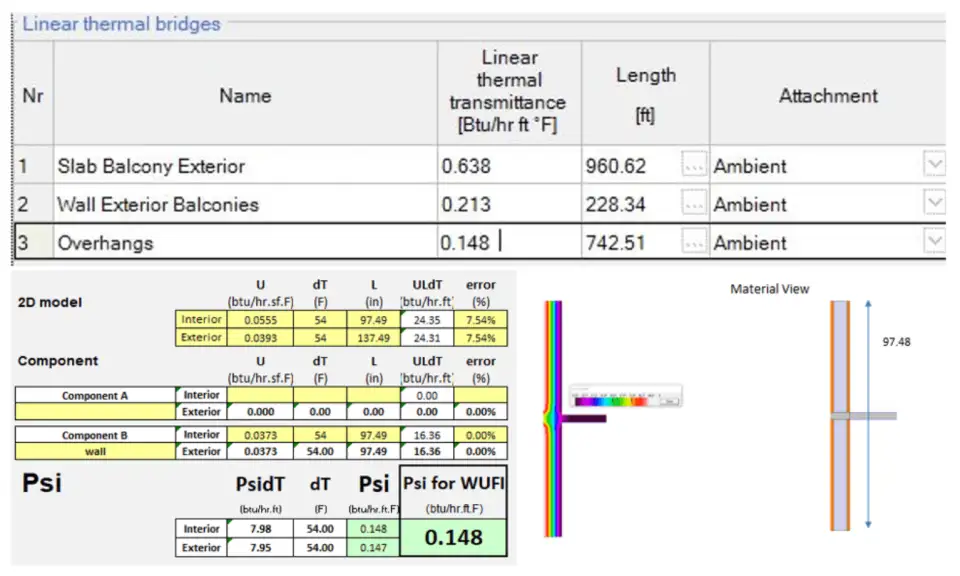

For the six-story buildings, a similar WUFI analysis was made (see Figure 12). Resolving the balconies’ potential thermal bridges were of particular importance (see Figure 13).

To address the ventilation and cooling needs, a DOAS ventilation system was considered, consisting of a Swegon GOLD RX-35, integrated with a 14-ton DX dehumidification coil (168,000 BTU/h) to precondition the ventilation air and provide the additional dehumidification that the enthalpy wheel lacked. This approach provides the most economically feasible solution.

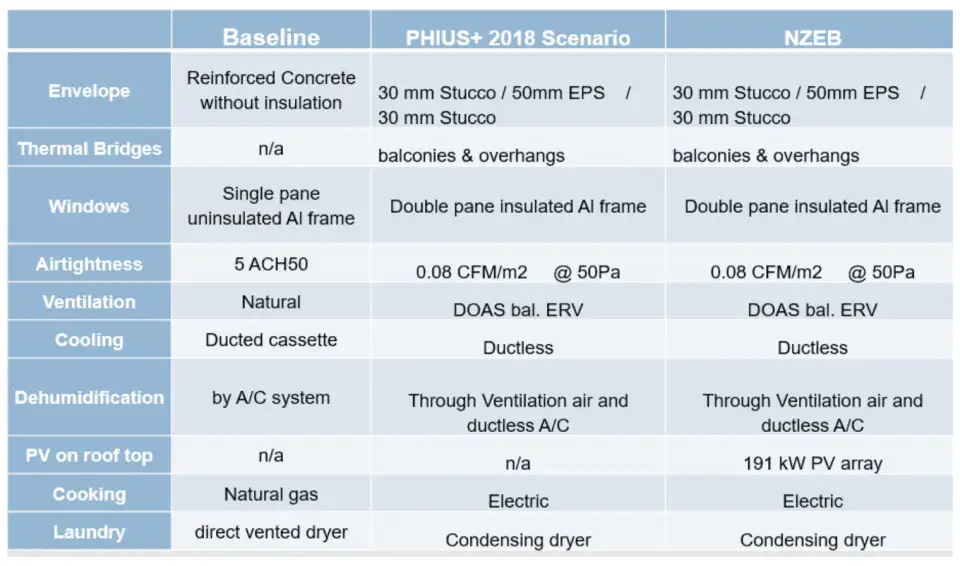

Path to Net Zero

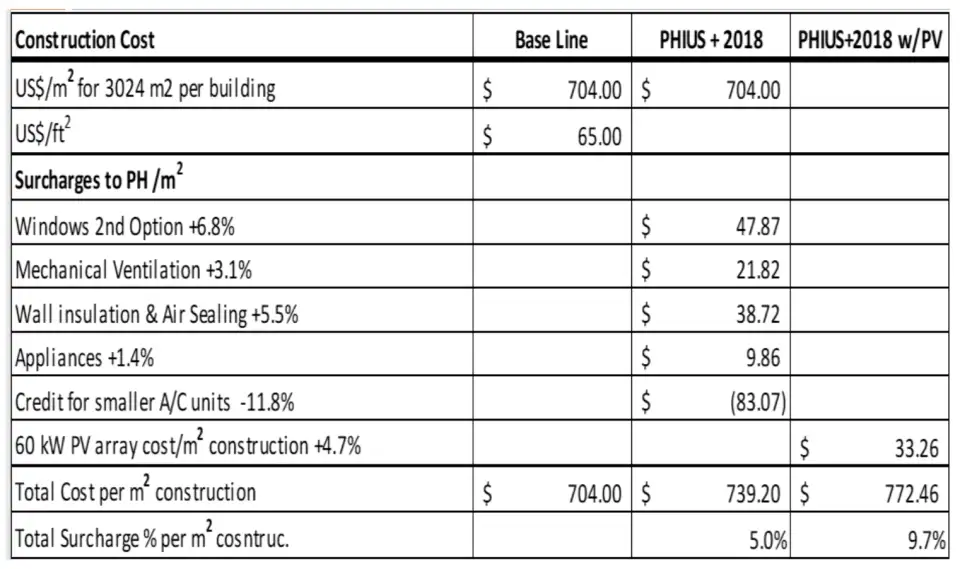

For a path to net zero, three scenarios were analyzed with WUFI Passive (see Figure 14). For each of these cases, the cost implications of the energy efficiency measures were calculated (see Figure 15). The windows had the highest incremental cost. However, since the time of this analysis, a new source for the windows has been developed that may reduce the cost of this component by 20%.

Due to roof area limitations, the largest PV array feasible on the roof is a 60-kW system, which can supply 91,295 kWh/year (32% of the required site demand), while occupying 70% of the roof area (400 m2) and having a return on investment (ROI) of approximately 2.5 years. For an NZEB, an array of 191 kW with a surface area of approximately 1,273 m2 would be required.

An adaptive WUFI model was also developed that set the interior temperatures at 25°C (77 °F) due to the temperature tolerance of the local population and the degree of dehumidification that can be achieved. Despite a 55% reduction in cooling demand compared to the baseline, the site energy increases, for reasons that remain unclear.

Tiny Houses

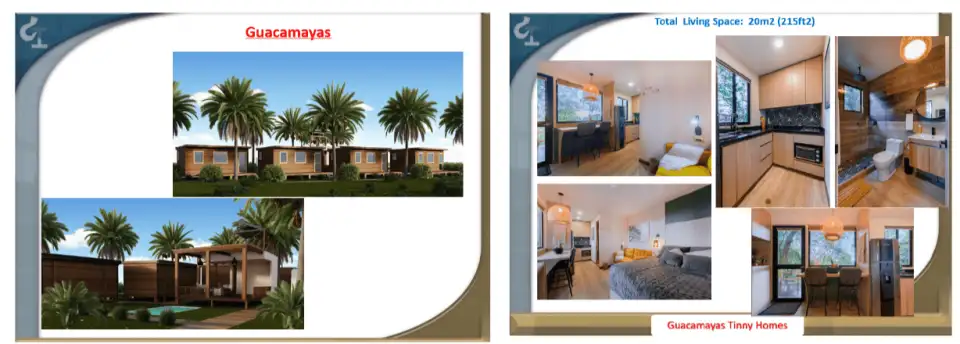

The developer is also experimenting with four tiny houses, each with a living area of 20 square meters (215 square feet) as a pilot for prefab units (see Figure 16). Although these tiny homes will not meet Phius standards, they were built following the guidelines of continuous insulation, air tightness, and the same quality double-pane windows that are being used in the single-family homes.

The wall system is a 2x4 stud with fiberglass batt insulation and exterior insulation of 20-mm (3/8-inch) EPS wrapped with taped Tyvek and a rain screen under the siding board. The following wall assembly detailed from outside to inside attains an R-value of 2.7 m2K/W (R-15.7 hr ft2 F/Btu).

Wood board 10 mm

Rain screen 20 mm

Tyvek wrap

EPS board 20 mm

OSB 10 mm

2x4s with fiberglass batt in cavity

Drywall

The roof assembly attains an R-value of 4.7 m2K/W (R-26.6 hr ft2 F/Btu).

2x4 with EPS in cavity

90 mm EPS

Metal roof attached directly to rafters

The floor assembly, detailed from closest to the ground to inside, achieves an R-2.5 m2K/W (R-18 hr ft2 F/Btu). The floor structure will be resting on concrete poles (see Figure 17).

Tyvek wrap--taped

Aluminum heat barrier 2 mm (R-3.9)

EPS 20 mm

2x4 with EPS in cavity 90 mm

Plywood 18 mm

10 mm (3/8-inch) EPS under the OSB

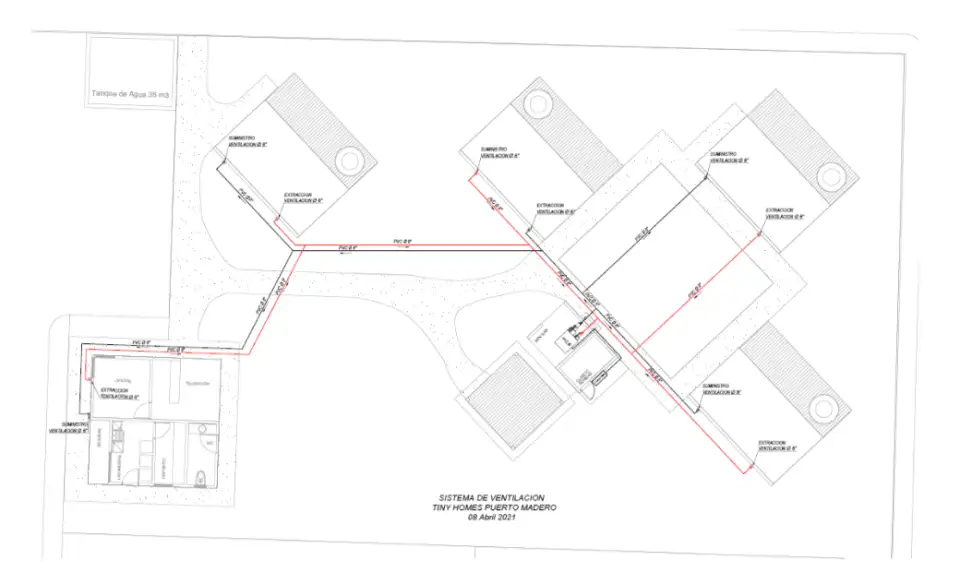

The ventilation system in this case will consist of a Ventacity VS250 CMe ERV coupled with a Fujitsu 9RLFCD system that consists of an indoor unit (ARU9RLF) and an outdoor unit (AOU9RLFC). The VS250 and the ARU9RLF will be housed in an insulated outdoor mechanical room, and the duct work from there to the four tiny homes will run underground (see Figure 18). The system was meant originally to ventilate the four tiny homes, as well as an administration office, but we decided to take the office out of the system to avoid too much head losses in the system. We could have used a Minotair PentaCare V-12 system here, but by the time we came across the Minotair, the Ventacity/Fujitsu system had been purchased already.

With Puerto Madero we are excited to be bringing some clarity to the challenge of reducing cooling loads in tropical climates while helping to meet the area’s housing needs.

-Enrique Bueno is a senior engineer, a CPHC with E+ Buildings in Montpelier, Vermont, and a partner in Consinfra.