Vladimir Pezel could not get comfortable in his apartment. During the summer months, the heat was torturous. During the winter months, his heating system would fail to keep up. He often found himself shutting off the heat pump at night, because it would just blow tepid air that would make him and his wife more uncomfortable while they slept. On particularly cold mornings, his toilet would freeze.

What may come as a surprise is that these are not the problems of an older building in some arctic outpost. These were issues plaguing Vlad’s townhouse-style apartment in Boston, and it seemed likely that it was due to a complete lack of insulation. “When I was changing the light bulbs in the recess lighting,” Pezel recalls, “I would feel cold air blowing on my face.” When he started to remodel the kitchen, his assumption was confirmed: the walls were hollow.

“The cold winds were blowing all throughout the walls, throughout the whole structure, and I remember thinking there must be a better way to live.”

If the experience aroused his interest in the green building movement, an article about the Passive House retrofit of a nineteenth century cottage in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston by Placetailor turbocharged it. It also encouraged Pezel to reach out to Placetailor about doing a Passive House project of his own. Two of the founding members, Declan Keefe and Simon Hare, agreed to meet Pezel for coffee.

While Pezel found it a bit odd that the two arrived on bicycles and claimed to not own any vehicles, he was fascinated by their worldview and their insistence on only building Passive House. After the meeting, Pezel and his wife decided they would be leaving their drafty apartment and working with Placetailor to build their own Passive House.

All they needed was a property.

The Somerville Property

“It was a local garbage dump, I guess, for the neighborhood,” Pezel says of the urban infill lot he and his wife purchased in 2011. Located in the city of Somerville and just a ten-minute walk to Cambridge’s famed Harvard Yard, the property had been home to five cinderblock garages on its northern edge, while the rest of the property had returned to nature. Beyond the garbage, Pezel remembers brush so thick on portions of the property that one had to use a machete to get from one side to the other.

Though the property was in rough shape, Pezel and the Placetailor team could see that the garages sat in a location that would be ideally orientated to make use of solar gains, so they petitioned the city to allow them to clear the structures. The city consented to the demolition, but many within the community were not happy the day the jackhammers arrived to raze the garages.

“There were like 50 or 60 calls to City Hall,” Pezel recalls.

To make it up to the neighbors, some of the staff from Placetailor went to a local bakery, bought several pies, and then invited everyone within earshot over to make amends for the noise. This spontaneous celebration gave them an opportunity to talk about Passive House design and to foster more community interest in the project.

Park Passivhaus

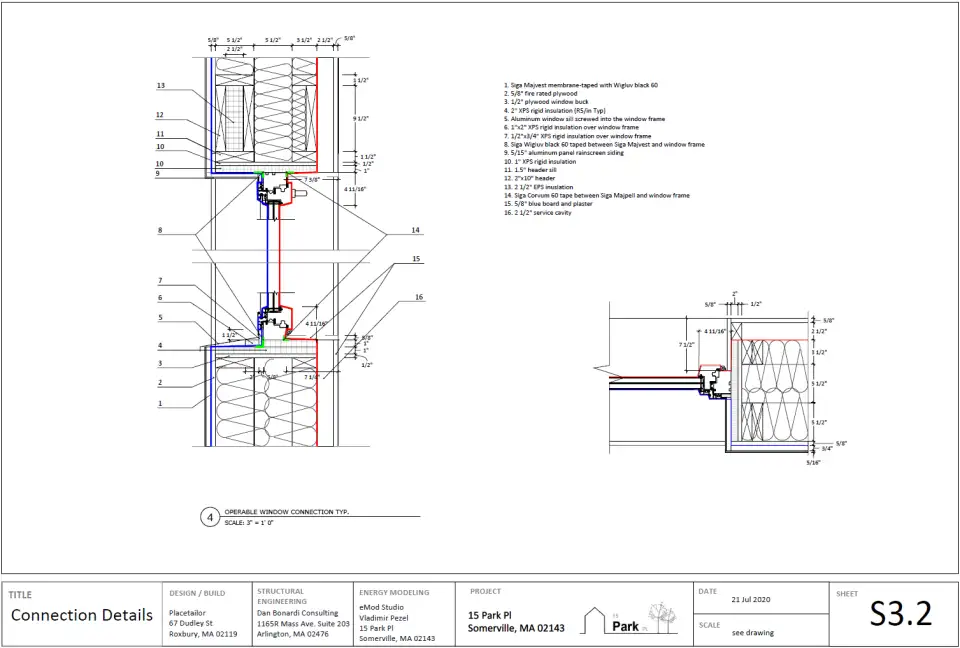

Construction of what became known as Park Passivhaus began in 2012. The two-story house contains three bedrooms, no basement, an unconditioned garage outside of the building envelope, and a treated floor area of 1,317 square feet. The design is simple to avoid thermal bridging, with windows situated in the middle of the walls and installed in line with the insulation.

The foundation is an 8-inch reinforced concrete stem wall with a Stego wrap vapor barrier and an inner shallow ring beam that has been thermally separated by 2 inches of mineral wool, while the floor joists have been filled with dense packed cellulose that extends below the joists. The walls are double-stud construction, with 2x6 exterior walls and 2x4 interior walls that are filled with 14.5 inches of dense packed cellulose. The roof assembly consists of Huber Zip panels taped with Siga Wigluv black 60 and a prefabricated scissor truss insulated by 20 inches of loose packed cellulose. The vapor control and air barriers were both provided by Siga.

Pezel says that this all resulted in some “pretty beefy” R-values. The R-value of the wall assembly is 56, while the R-values for the floor and roof are 61 and 76, respectively.

With respect to windows, the team opted for wood frame with aluminum cladding. In keeping with conventional Passive House construction, they are triple pane, tilt and turn. The door is also made of wood with a cork core and aluminum cladding. The windows and the door were manufactured by the Slovakian firm Makrowin and have U-values of 0.814 W/(m2K) and 0.754 W/(m2K), respectively. Surprisingly, Pezel says that the team found it relatively easy to obtain these components, because there was a distributor of high-performance fenestration systems already operating in the Boston area.

A solar thermal system located on the roof provides domestic hot water, while the heating and cooling come from a Mitsubishi mini-split heat pump system that consists of one condenser with a 22,000-Btu/hr capacity and two indoor evaporator units with a 9,000-Btu/hr capacity. Ventilation is provided by a Zehnder ComfoAir 350 HRV. To avoid overheating, Pezel has installed some shade sails over the patio door and the kitchen window, as well as some wooden slats to reduce the impact of the summer sun. Consequently, there are only a few weeks in August when it has been necessary to turn the AC on.

Some of the other benefits that Pezel has observed since moving into the home in April 2013 should be familiar to Passive House advocates. He notes that the walls and windows are never cold to the touch, even in the dead of winter. It’s also extremely quiet and likens it to being in a cocoon.

However, perhaps Pezel’s favorite benefit of living in a Passive House was realized after he installed a 4.8kW photovoltaic system on the roof in 2016 and made the house a net-positive building. Prior to this time, he says he paid between $60 and $80 per month for energy. Since installing the system, the utility company has been issuing him a credit, because the system pumps more energy into the grid than the family uses over the course of the year.

To take advantage of these energy savings, he and his wife are considering buying a pair of electric bikes.

To Certify or Not to Certify

Pezel says the intent had always been to have the house certified by the Passive House Institute. However, as the project wore on through 2012 and into 2013, Pezel says a feeling of “construction fatigue” began to settle in. The team at Placetailor were eager to move on to the next project, while Pezel and his wife just wanted to move into their new home, which they did in April 2013. Everyone figured they would get around to certifying the house later.

Fast-forward to the beginning of 2020 and “later” had turned into nearly seven years. Though the house remained uncertified, it was still performing exceptionally well, and Pezel was still interested in Passive House and building science. He also found himself at a crossroads in his career.

It was at this point that Pezel decided that he would get the house certified and that he would be the one to do it. He began studying for his certified Passive House designer (CPHD) exam, which he planned to take in March 2020. No surprise, the exam was cancelled twice due to the pandemic, and he instead decided that he would obtain the designer certification by certifying his own home—what he characterizes as the “two birds with one stone” approach.

In September 2020, Park Passivhaus received Passive House Plus certification from PHI with Pezel obtaining his CPHD certification in the process. Since then, Pezel has started his own CPHD consultancy, eMod Studio.

-Jay Fox

Heating Demand = 4.42 kBtu/Ft2/yr

Cooling Demand = 1.58 kBtu/Ft2/yr

Source Energy = 14.87 kBtu/Ft2/yr

Air leakage = 0.43 ACH50

All images and details courtesy of Vladimir Pezel.