When we transform poorly performing buildings into Passive House buildings, the benefits that result are numerous. Still, many Passive House retrofits face two hurdles. First, Passive House retrofits require an upfront investment. Where does that capital come from? Second, the ongoing and long-term financial value created by these Passive House retrofits often accrues to the people who live and work in the buildings—the tenants—not the building owners who are responsible for making that upfront investment. (This mismatch between who invests and who benefits is called the split incentive problem.) Unless a building owner is confident that the market will properly value the benefits of Passive House in the form of higher rents, lower vacancies, or a higher sales price, then how can she justify making the investment?

The solution may lie in reimagining the Passive House retrofit as a powerplant of “negawatts”. MEETS (metered energy efficiency transaction structure) does just that.

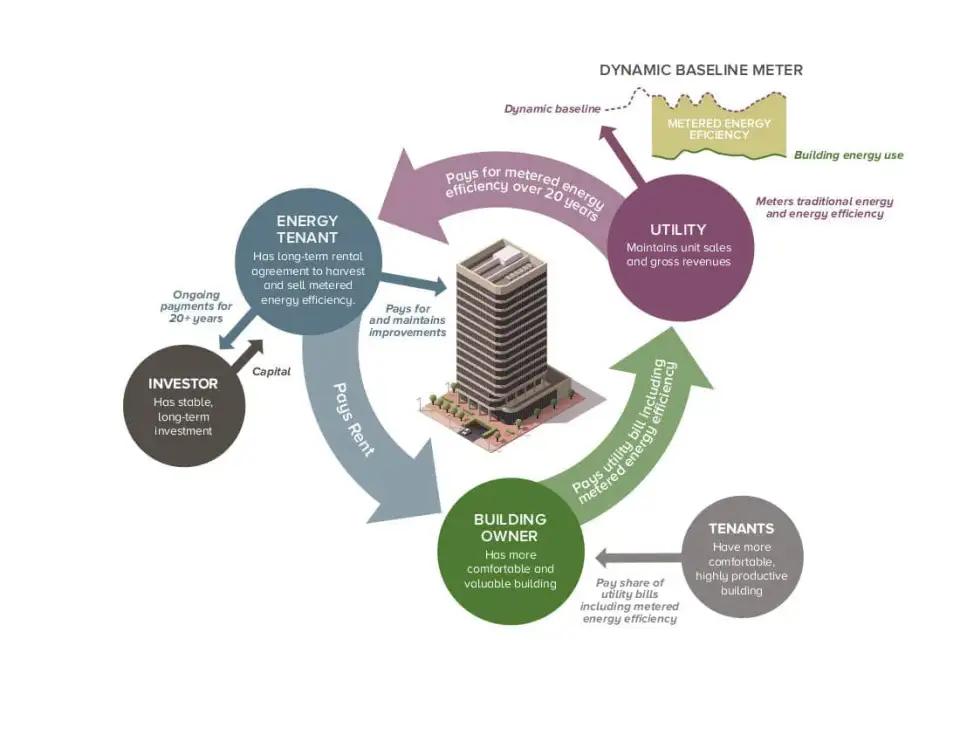

The MEETS model begins with an energy efficiency project developer, called the EnergyTenant™. The EnergyTenant signs a long-term agreement with the building owner. (The building owner can also take on the role of EnergyTenant.) The EnergyTenant pays for, installs, and maintains the energy efficiency improvements in the building—in this case, the Passive House retrofit. Just like any tenant improvement, these upgrades immediately belong to the building owner. The energy efficiency is then metered by a dynamic baseline meter that determines the delta between the building’s actual energy use and the modeled energy use of the building, had it not been improved (or, in the case of a new building, had it been built to code minimum). The readings are transparent and auditable.

The meter reports the energy efficiency, or negawatts, to the utility in the form of kilowatt hours or therms. The utility signs a long-term contract, or power purchase agreement, with the EnergyTenant to buy the energy efficiency, just as if it were buying energy from a traditional energy generator. In fact, stakeholders are now referring to this resource as “Efficiency Energy”, The EnergyTenant then takes a portion of the revenue it receives from the utility to pay rent to the building owner. The utility charges the building at retail rates for the metered energy efficiency plus the building’s traditional energy use. The building’s actual tenants don't see any changes; they just get to be in a better building, while paying the same energy bill that they would have paid if the building had not been improved. If the building is sold, the MEETS framework stays in place. The EnergyTenant agreement continues with the new owner; it is an asset that increases the building's value.

In summary, under MEETS: an outside investor invests capital at no cost to the building owner; this EnergyTenant’s rent payments increase the building owner’s net operating income (NOI); tenants are happier; the energy efficiency investments in the building increase its residual value at point of sale; and the building's marketability is increased.

The MEETS model was piloted at the Bullitt Center in Seattle—one of the world’s first Living Buildings—thanks to work by Rob Harmon of the MEETS Coalition, Denis Hayes of the Bullitt Foundation, and the Seattle-based utility, Seattle City Light.

“I think MEETS is the most important policy innovation in building efficiency in many decades,” Hayes says. “The split incentive problem means that tenants, who have not made any investment in efficiency, reap all the benefits of lower utility bills. This results in a zero-sum game for everyone else. For anyone to gain, someone has to lose. Often the loser is the electric utility, which does not want to give money so that its customers will buy less of the only product it sells. By clearly eliminating the split incentive problem, MEETS makes it possible to design win-win-win-win solutions—solutions that provide net benefits to every party. MEETS also provides a new income stream against which investors are willing to invest.”

“Passive House creates a tremendous amount of value for people,” adds Harmon. “Some of that value can show up in the form of lower energy bills, but the problem is that the building owner can’t then use the tenants’ lower energy bill value to build a better building. However, if you can aggregate utility bill savings and turn that into cash flow to build a better building, then you have something very powerful. MEETS aggregates utility bill savings value and turns it into something that tenants really want, which is a better building.”

Seattle City Light has expanded its MEETS pilot (also dubbed EEaS, or Energy Efficiency as a Service) twice, once in early 2020 and again early this year. Meanwhile, Harmon says that utilities in New York State and elsewhere are examining the business case.

Would you like to see a MEETS pilot where you live? “Local utility interest in MEETS will be driven by the real estate community asking for it. So, if you want it, ask for it,” says Harmon. “We have a model that other utilities can see works. We just need folks to press their utilities to engage.”

(An earlier version of this article first appeared in NAPHN’s 2020 Owners Manual.)