Pembina Institute’s Reframed Initiative is a British Columbia-based program aimed at developing replicable deep retrofit solutions and scaling their implementation. Reframed teamed up with BC Housing and Metro Vancouver Housing Corporation to commission deep retrofit designs for six multi-unit residential buildings and invited multi-disciplinary teams to participate in a six-month Reframed Lab to design solutions for these buildings. What follows is an account by one of the Lab participants, Ruffy Ruan, a mechanical engineer and Passive House consultant with Impact Engineering.

It was a white Christmas in Vancouver last winter, and temperatures were dropping as low as -15°C. Having been a mechanical engineer for a while, the first thought that came to my mind was, “Oh no, that exceeds the winter design temperature of Vancouver. I wonder how the ASHPs and boilers are operating?”

As the harsh reality of climate change continues to unfold, Reframed Lab hosted its debut workshop in January 2022. With six design teams and enthusiastic participation from the stakeholders, the workshops have never been quiet. From January to June we were like an extended family, reunited on a monthly basis.

At each workshop a special guest was invited to give additional insight into a specific topic. Workshop 1 was about regeneration, and we learnt how to better engage design with the community being served and to expand our understanding of how design can draw from and integrate human, social, and natural aspects. Workshop 2 discussed climate and seismic issues, teaching us to focus on long-term design metrics to correspond to unpredictable weather events. Our eyes were also opened to integrating green retrofits with the structural elements needed for seismic upgrades in order to strengthen the financial case for envelope upgrades, making them more feasible in British Columbia—a province where utility costs are just unbelievably low. Another workshop focused on health and well-being, and we got exposed to such concepts as trauma-informed design, biophilic design, and colour psychology to improve a building’s indoor comfort, accessibility, visibility, and durability.

As a mechanical engineer, it is refreshing and exciting for me to get connected to all these elements. We are no longer the captive of just meeting energy and carbon reduction targets; we are applying our imagination and our engineering skillsets to creating and designing buildings that are not only efficient but also visually pleasing to live in and healthy to stay in. We have been gradually shifting our focus to a more holistic approach.

The format of the workshops has also brought a sense of fresh air; you are no longer alone in your own silo trying to take the burden of the whole world on you. Ideas have been exchanged—not just among the members of one team, but six in total. The parallel design process of six design teams has sparked myriad discussions and sharing of expertise on the meaning of a deep retrofit. We compare the similarities and discrepancies between the design options. Everyone’s design strategies have been challenged not only by the stakeholders, the clients, but also by our peers. Some are riskier than the others, whilst some test the boundary between practical implementation and innovative ideas. Ideas are brewing, simmering, and jumping around; stress is building, filtering, and pushing hard; the concept has slowly but gradually been formed from the outline, the form to the shape.

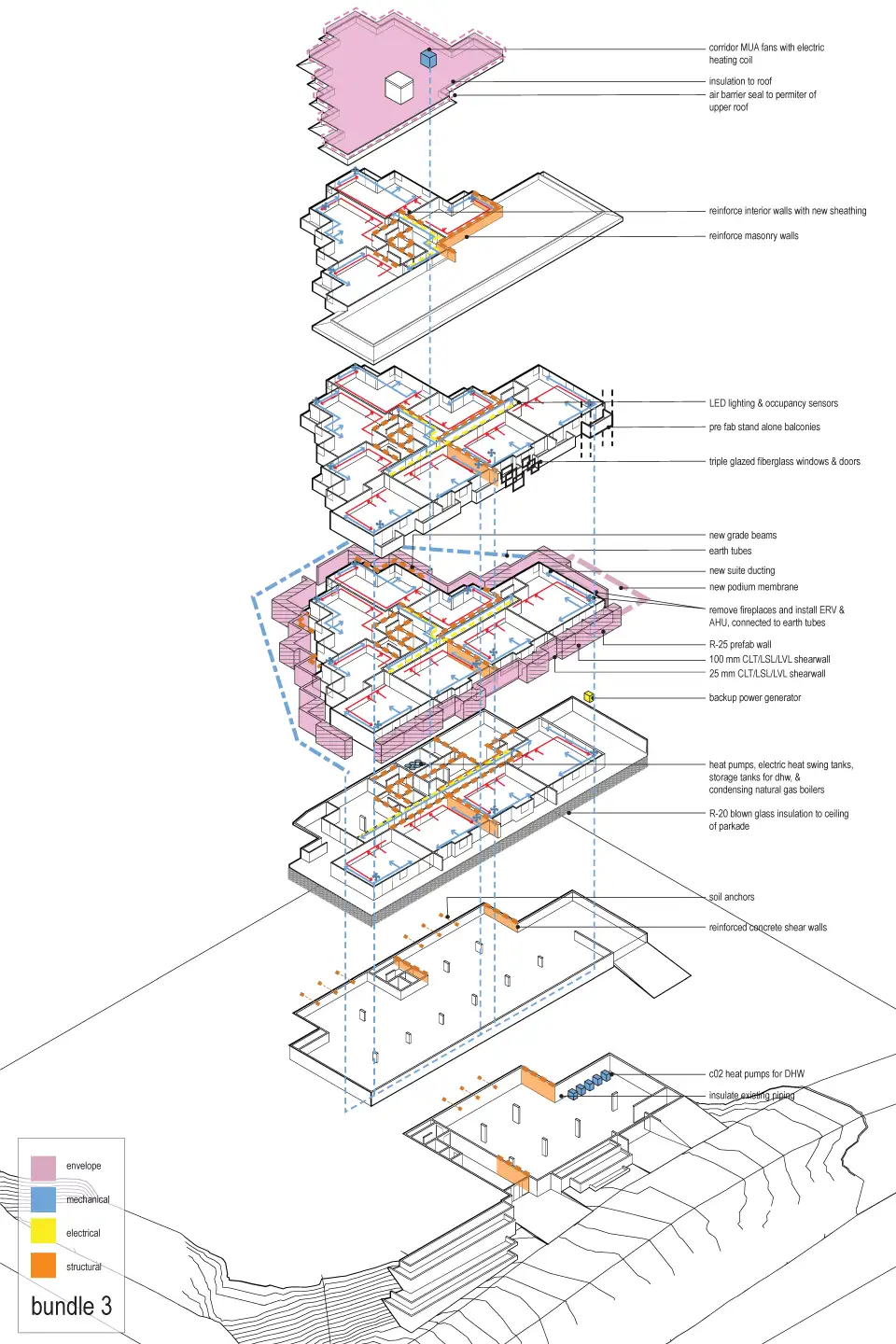

For Le Chateau—a three-story, 24-unit building in Coquitlam that serves as housing for families, seniors, and people with disabilities—the team includes a bunch of designers who like to challenge boundaries and think outside of the box. Patrick Roppel from Evoke Buildings has been pushing hard on prefabrication, while Tim White, the structural guru, has worked out the perfect solution for improving the existing structure. I and Ben Mills, also from Impact Engineering, introduced an emerging company that manufactures an “all-in-one” product that incorporates everything from heating and cooling to ventilation into one simple box. It eliminates the need for an external condenser, which you can often see hanging outside or positioned “indifferently” at roof level as part of the traditional VRF system. And, its compact footprint fits conveniently within the chase occupied previously by the fireplace flue.

Working on retrofit buildings is a completely opposite process from new construction; for the latter you start from scratch on a piece of blank paper, and for the former you are given the outcome at the outset of the project and from that you observe, you contemplate, you decompose, and you deduct to come up with a solution to fit within the restraints. Previously collected data sets are key to understanding how the building has been performing, or poorly performing, thus far, although they are often luxury items for buildings that are more than 20 years old. Then, educated assumptions have to play a role with detailed attention being paid to trace any possible evidence left behind. You don’t have a lot of cards in your hands, and there is no “magic” card to solve everything.

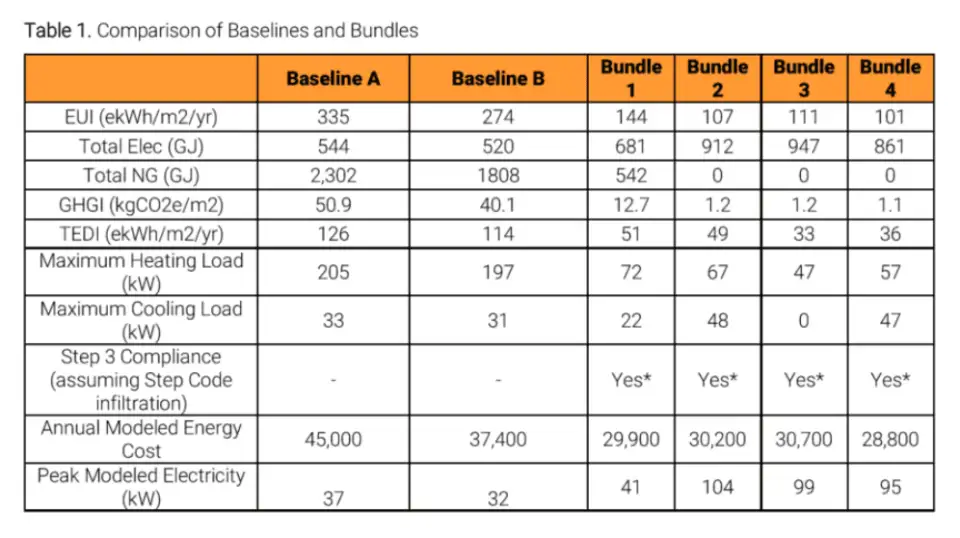

For each design team, we have been instructed to come up with four design options. Option 1 is to achieve 50% GHG reductions; options 2 and 3 are to achieve 80% GHG reductions; option 4 aims for maximum GHG reduction and full electrification (see Table 1). Scalability, speed, minimized disruption to tenants, and embodied carbon are the metrics to be considered. From a mechanical design perspective, the challenges lie in the restraints imposed by existing structural loads and electrical capacity. Testing the fine line between full electrification and a full electrical upgrade is a science but also a piece of art. The scale of the mechanical upgrade is also closely connected to the envelope upgrade, with all the moving parts driving each other around. A whole building approach is essential to ensure a holistic solution is formed without one overlooking the other.

The climate is on the horizon of becoming hotter and hotter, and cooling has become the most heated topic after Covid, which dominated 2021. The majority of existing buildings are not designed to combat the extreme weather events that have occurred more frequently in the past few years. The appearance of mandatory cooling within residential buildings triggers another increasingly heated topic: the embodied carbon associated with refrigerants. The tiny leakage of one drop of refrigerant can completely erase all the hard work done to ensure operational carbon savings. Refrigerants are a double-edge saw; they are essential elements for generating coolth and for electrification, but at the same time their global warming potential impacts can not be neglected at the slightest scale.

For Le Chateau we have explored both active and passive cooling strategies. In the scenario of active cooling, we have proposed the all-in-one product that is a simple plug-in, has a compact footprint, and reduces the amount of refrigerant charge. In the scenario of passive cooling, we have proposed an earth tube to utilize the earth—the free source of energy to pre-cool the incoming air during summer peaks and heat dome periods. The heat exchange between the scorched, hot 38°C air and the constant, calm 12°C ground acts as the perfect natural refrigerant for supplying coolth to the spaces. There are certainly huge challenges associated with the practical and financial elements of applying this strategy to an existing building, but there is no silver bullet to every solution, and we have to assess each option on a case-by-case situation to pick the battles we truly believe to be worth fighting for.

It is a hot summer again; the sun’s rays are filtering through the luscious tree leaves. Another heat wave warning is starting to be broadcast in the news. Today’s abnormal temperature rapidly is becoming tomorrow’s normal temperature. Our battles of fighting global warming will not be straightforward. The Reframed process has offered a platform for like-minded designers to gather and openly discuss our strategies for this tough battle. There is always that saying,” three heads are more than one head”. We are facing the climate emergency, and the only way to mitigate this human-made crisis is to collaborate, to cooperate, and to work together as a united frontline.