Renderings courtesy of GBBN

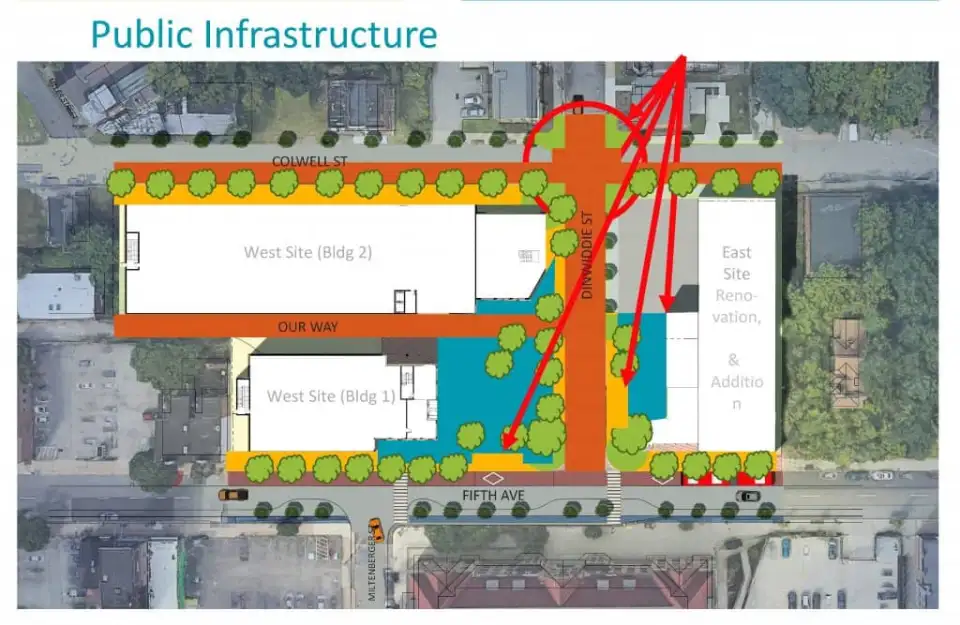

Bridging the Gap Development is jumping to the next Passive House level—with élan. After successfully incorporating several Passive House elements into its Miller Street Apartments, Bridging the Gap plans to make a major statement with its newest development, Fifth & Dinwiddie. The Fifth & Dinwiddie development straddles two sides of a street in the Uptown neighborhood of Pittsburgh. On the east side Bridging the Gap is renovating and expanding an existing building to create 40,000 square feet of commercial space. Across the street, a new mixed-use building is going up that will have 172 units of market-rate and affordable housing plus 10,000 square feet of retail space on the first floor. Both projects are targeting Passive House certification.

The sites are within an Eco-Innovation District in Pittsburgh, adjacent to a bus rapid transit (BRT) service stop. The district was established in part to encourage balanced, equitable, and sustainable development. Fifth & Dinwiddie aims to set the bar even higher by creating sustainable and resilient communities while also providing skills training and employment opportunities for the local workforce. The renovation of the former public works maintenance garage on the east site was set to begin at the end of 2020, but the challenges associated with COVID-19 resulted in a six-month delay. Construction is on schedule to begin in the summer of 2021.

Fifth & Dinwiddie got its start when Derrick Tillman, President & CEO of Bridging the Gap, responded to a request for proposals issued by the Urban Redevelopment Authority of Pittsburgh, the city’s economic development agency. Tillman and his partners pulled together a dream team that included the AUROS Group as the owner’s performance advocate, which is providing evidence-based performance and Passive House expertise along with detailed cost estimating. Financing this project required a variety of funding sources, including tax credits, HUD financing, and statewide redevelopment funds. One source gave preferential consideration for committing to Passive House certification.

The scale of Passive House buildings in North America has been rapidly expanding in recent years. Even so, “these two projects are in the 1% club of Passive House,” says AUROS Group’s Craig Stevenson. To address the inevitable complexities

associated with a project of this size, Tillman assembled a comprehensive team that includes GBBN Architects, Michael Baker International, and evolveEA.

The planned scope of work, including doubling the existing building’s size on the east site, will almost double the typical Passive House retrofit challenges as well, as the group figures out how to achieve Passive House levels of performance in the older building, the new addition, and the sections where the two meet. The existing building, which is cut into a hillside, is two stories in front, and in the rear its one story is essentially buried in the hillside. The four-story addition will wrap two sides of the building.

Amanda Markovic, associate principal at GBBN, says everyone has been excited since day one to be working on the firm’s first Passive House building, noting, “We’ve been developing our passive design strategies and wanting to push the envelope on performance by actually pursuing Passive House certification.” She adds that after her first charette with the AUROS Group, she came away thinking, “Relying on architecture to reduce energy use, rather than installing a PV array, makes so much sense to me.” She is also enthusiastic about how the project’s sustainability goals will support the surrounding communities. “Passive House design enables resilient communities for the long term,” she notes.

The back-and-forth collaboration between GBBN and AUROS Group led early in the design phase to an innovative material choice. After the initial energy modeling indicated total energy use above their target, the group debated possible changes. Markovic was surprised to find that reducing the glazed area did not shift the results. More insulation was always a possibility, but then Stevenson suggested using wood framing instead of steel studs—and that led to a significant decrease in energy use. “Wood framing for a commercial building is atypical,” Markovic points out, so she and her team ensured that local code would support this use, which it does. Swapping out the steel for wood framing is also lowering the structure’s embodied energy.

The team was originally considering connecting into a new district energy plant located exactly three blocks from the site. Despite extraordinary support from Clearway Energy’s national and local leadership, the project was unable to support the costs associated with district energy due to the very low, expected energy consumption of Passive House buildings. There just was not enough anticipated load, based on building use types, to support the infrastructure costs associated with district energy.

The new building, dubbed Fifth & Dinwiddie West, will be offering a residential environment that affords easy access to outdoor spaces. The building fronts onto a landscaped public plaza, which doubles as a rapid bus transit line station, and features several rooftop terraces. To facilitate exercise opportunities, there will be bike parking and a gym on-site.

During design development, the team realized that using off-site construction may yield significant cost and schedule improvements. Blueprint Robotics, based in Baltimore, Maryland, had the requisite Passive House and multifamily experience and joined the team to deliver the full complement of project benefits. In fact, as the analysis progressed, it became clear that offsite construction would provide advantages associated with the envelope, mechanical systems, and power and communications infrastructure. The team plans to document the benefits to budget and schedule resulting from this marriage of Passive House and offsite construction.

“While our last project was not Passive House certified, it did incorporate Passive House components,” says Tillman. The positive feedback he heard from the residents there was a game changer for him. “We were doing the right thing,” he says. “We needed to also pursue Passive House here, and we wanted to go to the next level.”

For Fifth & Dinwiddie, the next level will include not only Passive House certification but also meeting the RESET Air standard for healthy indoor air quality (see “RESET Air”) and Fitwel. When well designed, the RESET Air monitoring system does not have to add a premium, says Craig Stevenson, AUROS Group, just as Passive House doesn’t, when the approach is designed in from the start. “If you repurpose the building automation and control systems—to include fire alarm, lighting controls, security and access control, and other operational technology systems—using open integrated systems, you can then bring in RESET Air capabilities at par,” Stevenson asserts.

Achieving Passive House and RESET Air within a set budget requires a team with the right experience. Tillman has checked off that requirement, bringing an extremely ambitious project from an early vision to a solid design for a resilient community that will benefit the Uptown neighborhood for generations.

Passive House Metrics

|

Heating energy |

4.3 kBtu/ft²/yr |

|

Cooling energy |

4.0 kBtu/ft²/yr |

|

Total Source Energy |

38.0 kBtu/ft²/yr |

|

Airtightness |

0.6 ACH₅₀ (design) |