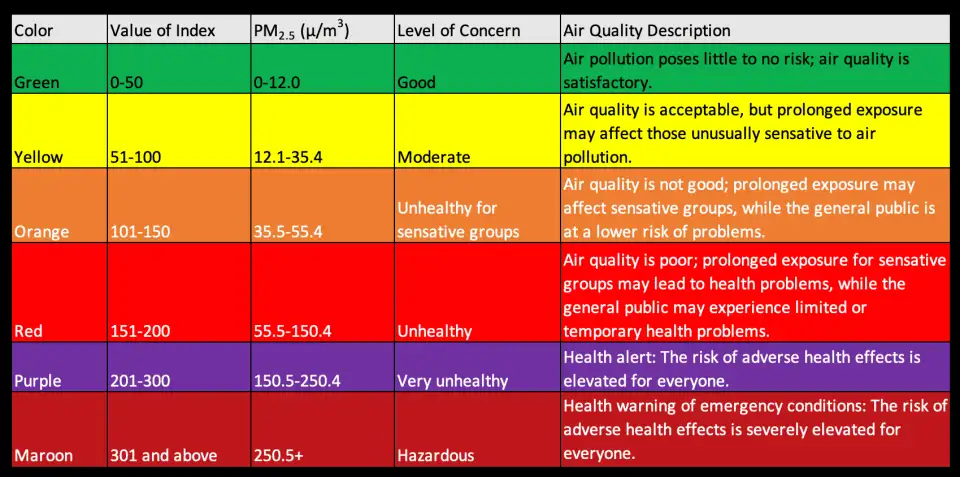

Much of the Northeast is choking beneath a thick blanket of smoke as Canadian wildfires in Ontario and Quebec continued to burn late into the week. Some of the worst smoke has descended upon major cities in the State of New York, including Syracuse and New York City. The latter had some of the worst outdoor air quality in the world for any major city on Tuesday, while the air quality index (AQI) in Syracuse exceeded 400 on Wednesday afternoon.

“It’s looks like a sci-fi movie,” according to Patricia Paz, a retiree and resident of Manhattan’s Upper East Side. “It is really weird.”

As of Wednesday afternoon, the severity of the smoke had turned the skies over the five boroughs an eerie shad of yellow and the oppressive smell of woodsmoke filed the air as the AQI approached 325. The smoke was so severe by midday that the Federal Aviation Administration issued a temporary ground stop for New York’s LaGuardia International Airport.

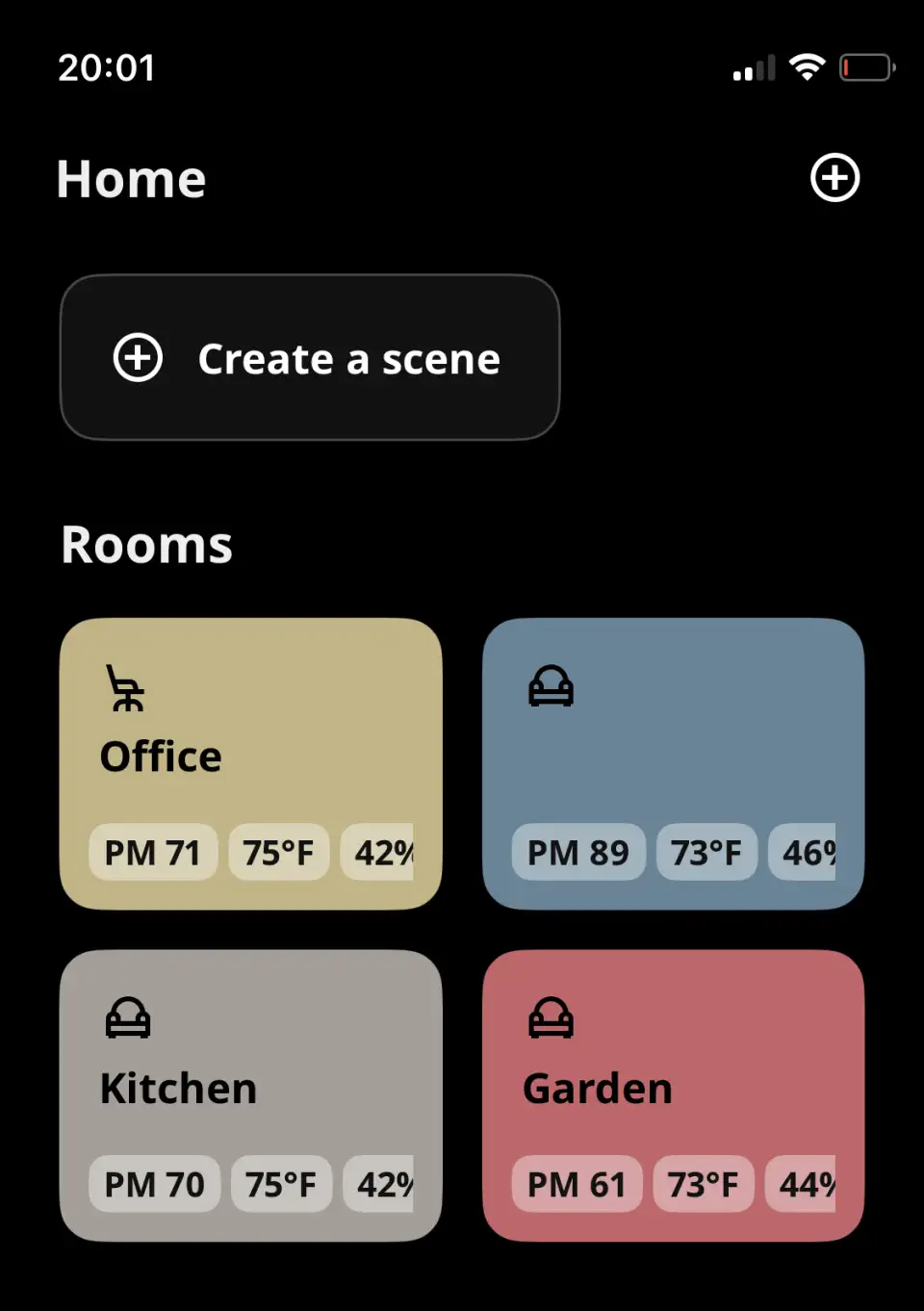

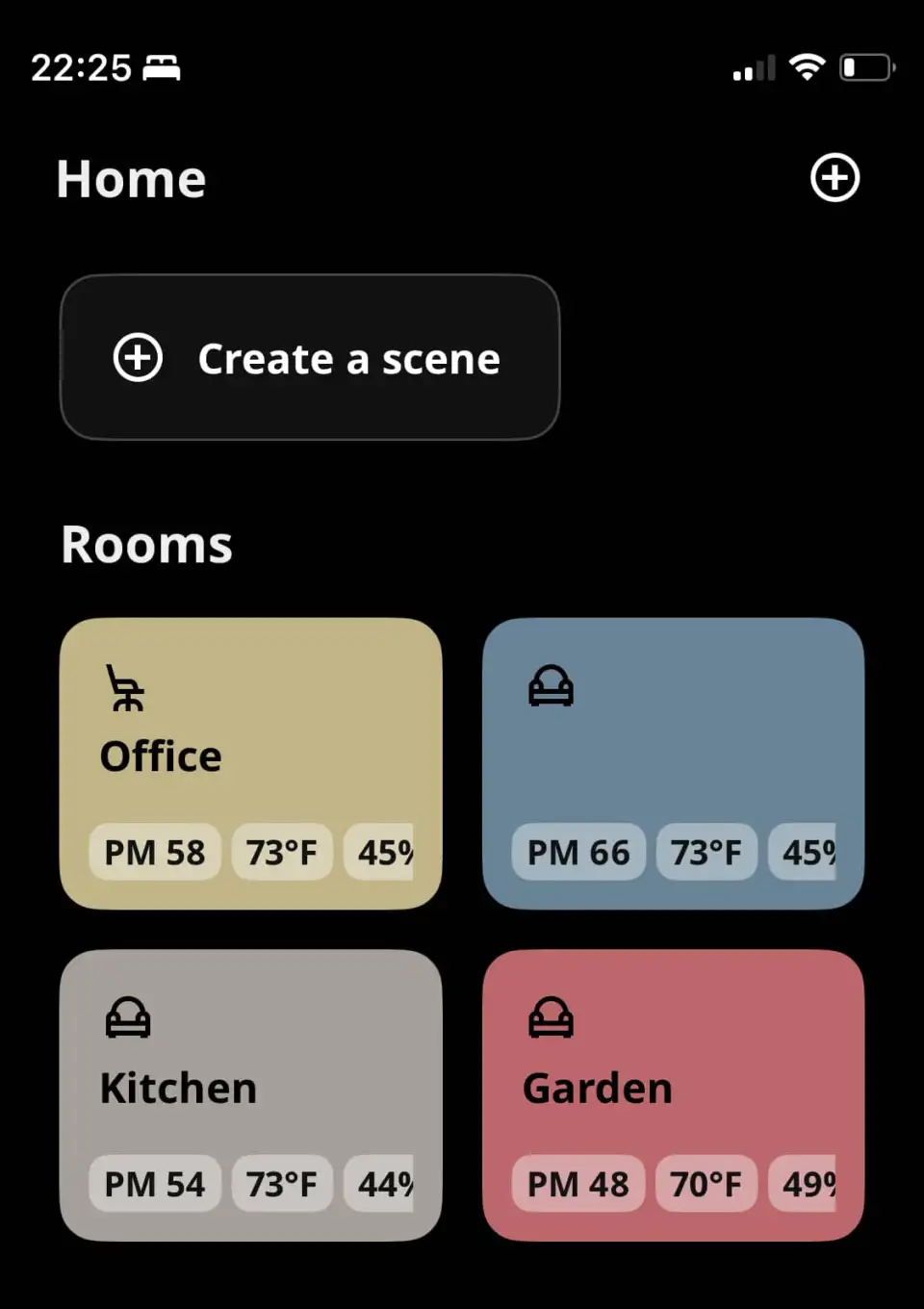

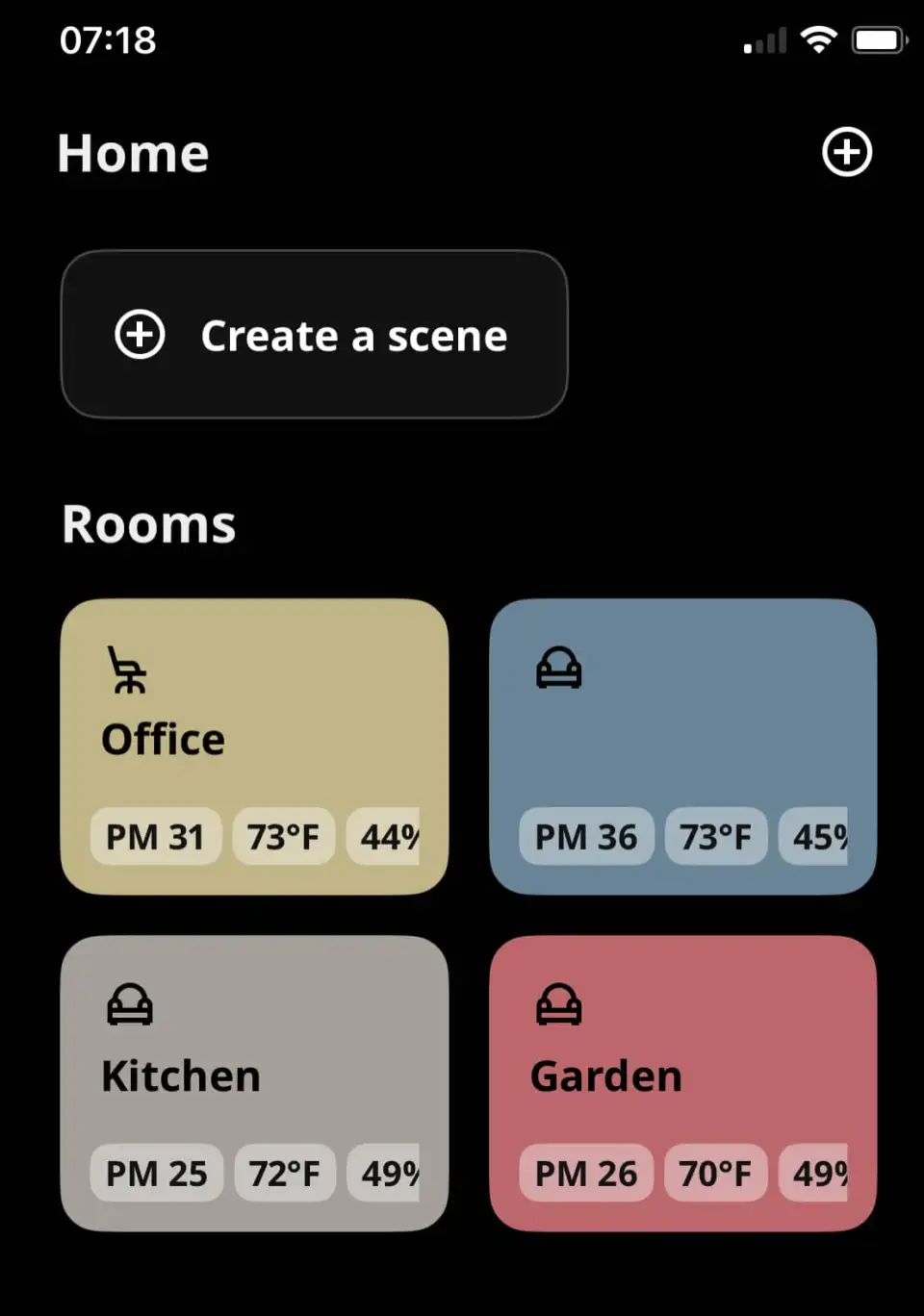

While the East Coast of the U.S. has largely been spared extreme wildfire events over the years, the extent of the smoke from the Canadian fires is a reminder that people from hundreds or even thousands of miles away can be impacted. Consequently, smoke resiliency is not just an issue for those who are in near areas that are prone to fires; it can even affect those living half a continent away.