In May 2024 the European Union adopted an updated Energy Performance of Buildings Directive that requires all new residential and non-residential buildings to be zero-emission buildings (ZEBs) as of January 1, 2028 for buildings owned by public bodies. This requirement will apply to all other new buildings as of January 1, 2030, with some possible specific exemptions. A ZEB is defined in the directive as being one that has no on-site carbon emissions from fossil fuels and a very high energy performance.

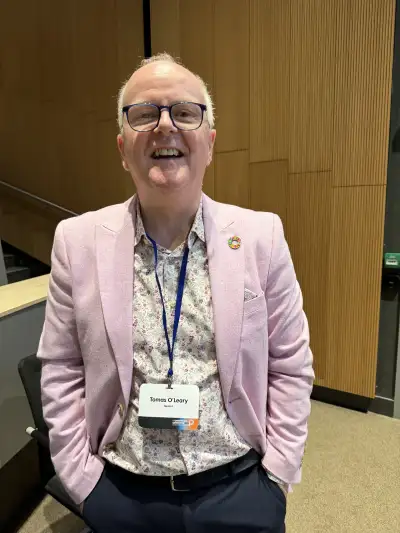

“We're dropping the nearly, so we're going from nearly to zero, and the ‘E’ changes from energy to emissions,” says Tomas O’Leary, managing director of MosArt, a Passive House architecture, consulting, and certification firm based in Rathnew, Ireland. While he concedes that these changes may seem pedantic, the shift in language is actually quite important. “We're basically going from recognizing that we've been focused on operational energy up to now to that we need to think of the fuller gamut of all of the emissions, not just operational, but embodied,” he explains.