The Lirio is a joint venture by the Hudson Companies and Housing Works that takes its name from the Queens Giant, a 134-foot tulip tree (Liriodendron tulipifera) located in Alley Pond Park. Beyond its tremendous size, the Queens Giant is also notable for its longevity. It is believed to be around 350 years old, making it the oldest organism in New York City and meaning that it probably began germinating right around the time New Amsterdam became New York.

A Celebration of Longevity and Resiliency

If nothing else, the Queens Giant has demonstrated its resiliency over the centuries and the Lirio hopes to stick around for just as long. However, the decision to name the mixed-use development that has been designed to meet Phius standards after the tree has far less to do with the durability of the building and is far more a gesture of recognition to many of the Lirio’s future residents. More than half of the 112 units in this 100% affordable building currently under construction at the southeast corner of West 54th Street and Ninth Avenue in Manhattan will be reserved for the original survivors of the HIV/AIDS epidemic who are currently experiencing homelessness.

While HIV/AIDS has become increasingly treatable within the last two decades, a diagnosis was more or less a death sentence for those who bore the brunt of the initial waves of infections in the early 1980s. These individuals were predominately gay men in urban areas like San Francisco and New York City. The neighborhood where the Lirio is located, Hell’s Kitchen, was hit extremely hard by the epidemic. To this day, it continues to be home to one of the largest populations per capita of individuals with HIV or AIDS in the city, many who struggle with precarious housing situations.

“This is an important project for the neighborhood,” says Hudson’s Managing Director of Architecture Michael Ohlhausen.

The Roots of the Lirio

The original request for proposal (RFP) for the site was issued by the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) in 2018. The property had housed the 54th Street Bus Depot until the 1990s, when the depot was demolished and turned into a city-owned parking lot used by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). The property was later designated as part of the larger Western Rail Yards rezoning, a decades-long redevelopment plan that has evolved over the years, and is intended to spur high-density, mixed-used developments and the creation of more affordable housing in underutilized properties along Manhattan’s West Side.

Recognizing the need for not just affordable housing, but also supportive services for long-term survivors of HIV and AIDS within Hell’s Kitchen, the Hudson Companies joined forces with Housing Works, a New York City-based non-profit established in 1990 to resolve the twin crises of homelessness and HIV/AIDS, and then submitted their bid. In 2019, HPD awarded them the project.

While there have been disruptions along the way that have included the COVID-19 pandemic, delays with financing via HPD, and some back and forth with the local community board, construction formally began in summer 2024. When complete, the nine-story Lirio will consist of approximately 155,000 gross square feet, of which roughly 103,000 square feet will be conditioned residential space consisting of 112 units. Of the 112 units, 67 will be for formerly unhoused individuals. Of those 67 units, 59 have been set aside for long-term survivors of HIV/AIDS. The remaining units will be a mix of varying sizes, including one-, two-, and three-bedroom apartments—all of which will be for families earning between 40% and 80% area median income (except for one unit reserved for the building’s superintendent). Housing Works will manage the residential portions of the building and provide supportive services to eligible residents. The remaining square footage will be split between ground floor retail along Ninth Avenue and 44,375 square feet of space that has been reserved for the MTA.

Occupancy is expected in 2026.

Building a Strong Team

Hudson should be well-known to many within the Passive House community in New York and beyond, largely because of their work on such large-scale projects as The House at Cornell Tech and the redevelopment of Brooklyn’s Greenpoint Hospital. The former, a student residence, is one of the most prominent buildings on Roosevelt Island and was at one time the largest building in the world to be certified by the Passive House Institute. It was also one of the first large-scale Passive House projects in New York City.

CetraRuddy, the architecture firm behind the Lirio, is relatively new to Passive House. The Lirio was their first passive project when design started. (Design of Clarkson Estates, a 328-unit passive project in Central Brooklyn, started after the Lirio, but has followed a more accelerated timeline and broke ground at the end of 2023.) While CetraRuddy may not have deep roots in the Passive House community, they have certainly made their mark on New York City, as the award-winning firm has been responsible for several buildings that have given new shape to the contours to the Manhattan skyline, including Rose Hill (30 East 29th Street), 200 East 59th Street, and One Madison Park.

Ohlhausen explains that CetraRuddy’s design bona fides were one of the reasons Hudson decided to go with the firm. “We wanted a strong design architect with a really good design reputation to submit something that would impress the HPD and the agencies and whoever was looking at the RFP,” he says. Ohlhausen notes that Hudson had also established a good relationship with CetraRuddy, as they had worked together on a market-rate building in Central Brooklyn known as the Lois.

Other members of the team include EP Engineering as MEP engineers, Bright Power as the sustainability and Passive House consultant, and Consultant Associates of New York (CANY) as the building envelope consultant.

Project Team

Architect: CetraRuddy

Developers: The Hudson Companies and Housing Works

MEP Engineers: EP Engineering

Sustainability/Passive House Consultant: Bright Power

Building Envelope Consultant: Consultant Associates of New York

The Lirio in Depth

From the start, the Lirio was intended to become Passive House and LEED Gold certified. As CetraRuddy Principal Brian McFarland explains, “Excellence in sustainability, including Passive House design, was a stated preference in the RFP.” However, the Passive House envelope will only include the supportive services and residential units, as well as the lobby and means of egress (including two stairwells: one that leads directly to the street and one that leads into the lobby). The ground floor retail and space for the MTA will exist outside of the envelope and be separated by an interstitial space between the second and third floors (see “The Malkovich Floor”). The MTA will inhabit almost the entirety of the second floor, just over half of the ground floor, and about 11,500 square feet in the cellar. The square footage in the cellar will be dedicated to mechanical or utility spaces, as well as parking for emergency vehicles.

The first two floors will not only be commercial spaces and outside of the Passive House envelope; they will also be shaped differently than the residential floors above. As designed, the building area on the two lower floors is rectangular, while floors three and above are U-shaped with multiple cutaways on the upper floors, as shown in the rendering. The courtyard created by this negative space will be sheltered from Ninth Avenue and West 54th Street and measure approximately 5,000 square feet—about four times larger than the typical courtyard in a New York City development, according to McFarland. The opening of the U-shape will look out to the backs of several low-rise buildings along West 53rd Street that sit approximately 20 feet above where the walking surface of the courtyard will be.

The result of this design will be an abundance of sunlight within both the courtyard and the units that look down into it. The two sides of the U-shaped residential portion of the building with street frontages—along Ninth Avenue and West 54th Street—will be double-loaded corridors, while the side that shares a lot line with the MTA rail control center will be a single-loaded corridor that looks out to the courtyard. The courtyard will provide not only daylighting, but also a small green space for the tenants. Approximately 40% of the surface area will be landscaped with vegetation, while the rest will be reserved for tenant recreation.

In addition to being the entry point into the courtyard, the third floor will also house a resident lobby, counseling offices and supportive services for the tenants with HIV/AIDS, and a small computer lab. The goal is to aid those struggling with what remains a highly stigmatized and medical condition with conventional counseling while also providing them with a means of learning new skills for career advancement or to rejoin the workforce.

The 59 units for the survivors have been designed to be efficiency studio apartments. They are snug—between 300 and 350 net square feet—but they will be quiet, peaceful, and comfortable. Per HPD’s regulations, the area occupied by a unit’s mechanical systems cannot be included in its habitable space (even if the space above or below the system is usable), so the team found a way to tuck the fan coils from the variable refrigerant flow (VRF) system beneath the window and to install what McFarland describes as a “vertical closet” next to it for the ventilation system. Consequently, space is not wasted on housing mechanical systems and each occupant has control over the temperature of their unit.

Providing a healthy space for the occupants is always a benefit of passive construction, but the team has worked to incorporate materials that have low volatile organic compounds (VOCs), including adhesives, sealants, interior paints, composite wood products, and flooring. McFarland says that all flooring installations meet criteria for FloorScore certification or a similar standard. To satisfy criteria for LEED Gold certification, they have also obtained material durability verifications and sourced local and post-consumer recycled components.

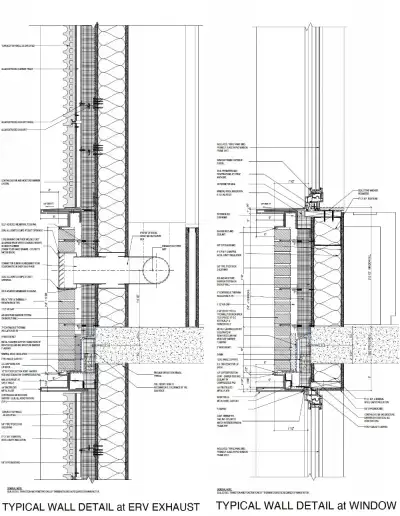

There are two distinct wall assemblies for the building: one that faces the street and one that faces the courtyard or abuts the rail control center to the east. The former (see details below) will be clad with either brick or terracotta panels that match the textual context and palette of the neighborhood. Beneath will be a 3-inch layer of continuous insulation (mineral fiber), an air and moisture barrier system, exterior sheathing, and then 6 inches of mineral wool insulation within the metal-framed walls. McFarland says that special steps are being taken to minimize thermal bridging. For example, wood blocking will be installed under the windows to receive the exterior metal sill trim. Meanwhile, the stems of the brick ties will be coated in plastic to prevent thermal bridges and a thermally-broken shelf angle support will be used to allow for continuous insulation behind the angle. The former product is manufactured by Hohmann & Barnard and the latter is manufactured by Fero.

The team decided to use a 7-inch exterior insulation and finish system (EIFS) for the walls that will not face the street. “The EIFS allowed us to increase the average thermal resistance of the walls, and it creates fewer opportunities for thermal bridges as it doesn’t have all the ties and the connectors that the brick has,” McFarland notes. The fenestration systems for both wall assemblies will be uPVC-framed with triple glazing and manufactured by INTUS. The windows will be recessed approximately 8 inches back from the surface of the wall to reduce summer solar gains. They will also be outfitted with interior shading devices except on the north-facing wall.

The roof will be home to the compressors for the VRF system and other mechanicals, as well as a small PV array, but the vast majority of the surface will be green. The green roof assemblies both comply with Local Law 90 and assist with stormwater management. To further reduce heat absorption, all exposed roofing membranes will have a solar reflectance (SR) value of 0.65 or greater, while the paving materials in the courtyard will have an SR value of 0.28. (For reference, SR values run from 0-1, with darker materials having lower scores. Typical dark roof membrane materials score 0.20 or less.) The roof assemblies will be equipped with vacuum insulated panels (VIPs), which provide exceptional thermal performance. Despite being only 2 inches thick, they achieve an R-value of 49. The VIPs will be protected by 1.5 inches of extruded polystyrene (XPS) insulation to give the roof a total R-value of 56.5—all contained within the continuous insulation layer.

Though construction has only just begun as of summer 2024, McFarland remains confident that the project will be successful, largely because so many members of the team are familiar with Passive House methodologies. “Almost everyone who is working on this project has done Passive House before,” he says. This includes Broadway Builders, an affiliate of the Hudson Companies that has worked on several Passive House projects in New York.

Ohlhausen agrees. “You really have to have a strong design team and make sure that you’re committed to passive from the beginning,” he says.

Model Performance Metrics

|

Heating demand |

4.20 kBtu/ft2/year |

|

Cooling demand |

5.97 kBtu/ft2/year |

|

Total source energy |

1,024,947 kWh/year |

|

Air leakage |

0.08 CFM50/SF |

The Malkovich Floor

Yes, the Malkovich Floor.

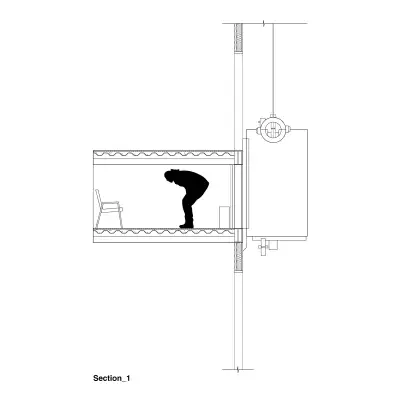

To satisfy stipulations within the project’s RFP, approximately 44,000 square feet within the Lirio will be reserved for the MTA as an annex to the adjacent rail control center. The spaces occupied by the MTA do not fall within the Passive House envelope. The MTA’s offices on the second floor and the third floor, which is where the residences begin, are separated by a three-foot interstitial space—the Malkovich Floor. According to McFarland, the MTA objected to the number of plumbing stacks that would need to pass through their spaces on the first and second floors, resulting in the need to design a nominal floor where the stacks could converge and be redirected to verticals adjacent to the stairwells. The Passive House envelope includes this nominal or Malkovich Floor, as well the verticals and the stairwells. One of the stairwells leads directly onto the street, while the other services the lobby for the residential units above.

The Malkovich Floor represents the bottom of the Passive House envelope, the underside of which is reinforced concrete slab. Between the reinforced concrete slab and the top of this floor are a series of parallel block walls with metal decking and concrete across them, McFarland explains. Unfortunately, this creates a myriad of cells. On its own, this design results in an overly complex web of compartments, but it is further complicated by the fact that the Malkovich Floor is adjacent to and directly beneath the courtyard, which creates additional opportunities for thermal bridging with the roof membrane. Ultimately, the design team found solutions to these challenges, but it wasn’t easy. Those who are considering building an interstitial floor with multiple blocked walls that is sandwiched between the bottom and top of the Passive House envelope may want to consider another option.

"Malkovich Floor" detail courtesy of Interiors.