For many rural towns—especially those that are staring down the barrel of obsolescence due to limited job opportunities, declining populations, and substandard housing stocks—large portions of the built environment are at a crisis stage. Keeping these towns thriving will require fresh economic opportunities, reinvestment, and a combination of retrofit projects and new construction that produces affordable, durable, and efficient homes.

Higher performing buildings are particularly important to low-income households in rural areas, because rural residents have a higher energy burden than individuals in suburban and urban communities. Median household energy burdens—defined as the percentage of household income spent on energy bills—among rural households is 4.4% (compared to the national average of 3.3%), and many rural, low-income households may see energy burdens exceeding 9.5%. However, finding the optimal balance between energy efficiency and affordability is never an easy task.

To help resolve this issue, a team based at Auburn University’s Rural Studio in Newbern, Alabama began in 2004 the 20K House, a research project dedicated to developing small, well-designed and affordable prototype homes that can also support a local workforce and rely on locally available materials. According to Mackenzie Stagg, a frequent collaborator with Rural Studio and assistant research professor at Auburn, “Each academic year, student teams design and build a small home for a local community member based on a conceptual proforma.” These prototypes are then named in honor of the homeowner.

“Expanding on the 20K House work, the Front Porch Initiative is a faculty-led endeavor developed to extend the impact of the research by working with housing providers outside of Rural Studio’s service area,” Stagg says. These partner organizations then build a product line of homes in their communities based on the prototype home designs. Additionally, faculty members offer the partner organizations guidance about codes and third-party certifications, as well as technical assistance.

Buster’s House

Recently, Auburn University’s McWhorter School of Building Science and the University’s College of Architecture, Design, and Construction (which includes Rural Studio) partnered with Auburn Opelika Habitat for Humanity to create two homes (House 66 and House 68) on the same street in the town of Opelika, Alabama, which is located in climate zone 3. Both projects modeled their homes on Buster’s House, a two-bedroom, 900-ft2 prototype already developed by a team of Rural Studio students in 2017. They were also modified to meet FORTIFIED Gold programs, designed to protect against severe wind damage.

The primary distinction between the two homes was that House 66 was built to meet Phius requirements, while House 68 was built to meet the U.S. Department of Energy’s Zero Energy Ready Home (ZERH) standard. The former house was designed and constructed in the spring and summer semesters of 2018, and the latter house was designed and constructed in the spring and summer semesters of 2019. Side-by-side energy monitoring of the two homes is being conducted under the auspices of the Front Porch Initiative.

In each instance, students, faculty, and energy consultants performed extensive energy modeling to examine different iterations of Buster’s House to ensure compliance with the two standards and to better plan for assembly. Both homes were then built by student and faculty teams who worked with local volunteers, which both reduced construction costs and offered the students the opportunity to engage with the community and gain first-hand knowledge of what it’s like to work on a construction site. During preliminary blower door tests, students also saw firsthand how Passive House principles can impact a building’s performance, and this experience transformed the theoretical into the practical. David Hinson, professor in the architecture program at Auburn and frequent collaborator with Rural Studio, describes the experience as “one of those teaching days I’ll always remember.” He adds, “You could see the light bulbs.”

In addition to providing quality affordable housing to two families in Opelika, the objective behind this project was to then monitor the energy performance of each of the homes to better understand the optimal means of designing and constructing small, single-family detached homes within an affordable cost-to-construct framework without sacrificing performance. As Hinson explained, rather than starting at code and asking what improvements can be justified according to costs, he wanted to start at the Passive House standard and build House 66, and then see what alterations could be made to reduce costs without significantly sacrificing performance while building House 68.

Hinson added that there were three primary questions they hoped the project would answer:

What is the difference in cost to build to Phius vs. ZERH standards?

What is the difference in cost to operate homes built to Phius vs. ZERH standards?

How does the building design affect costs for homeowners?

House 66 at a Glance

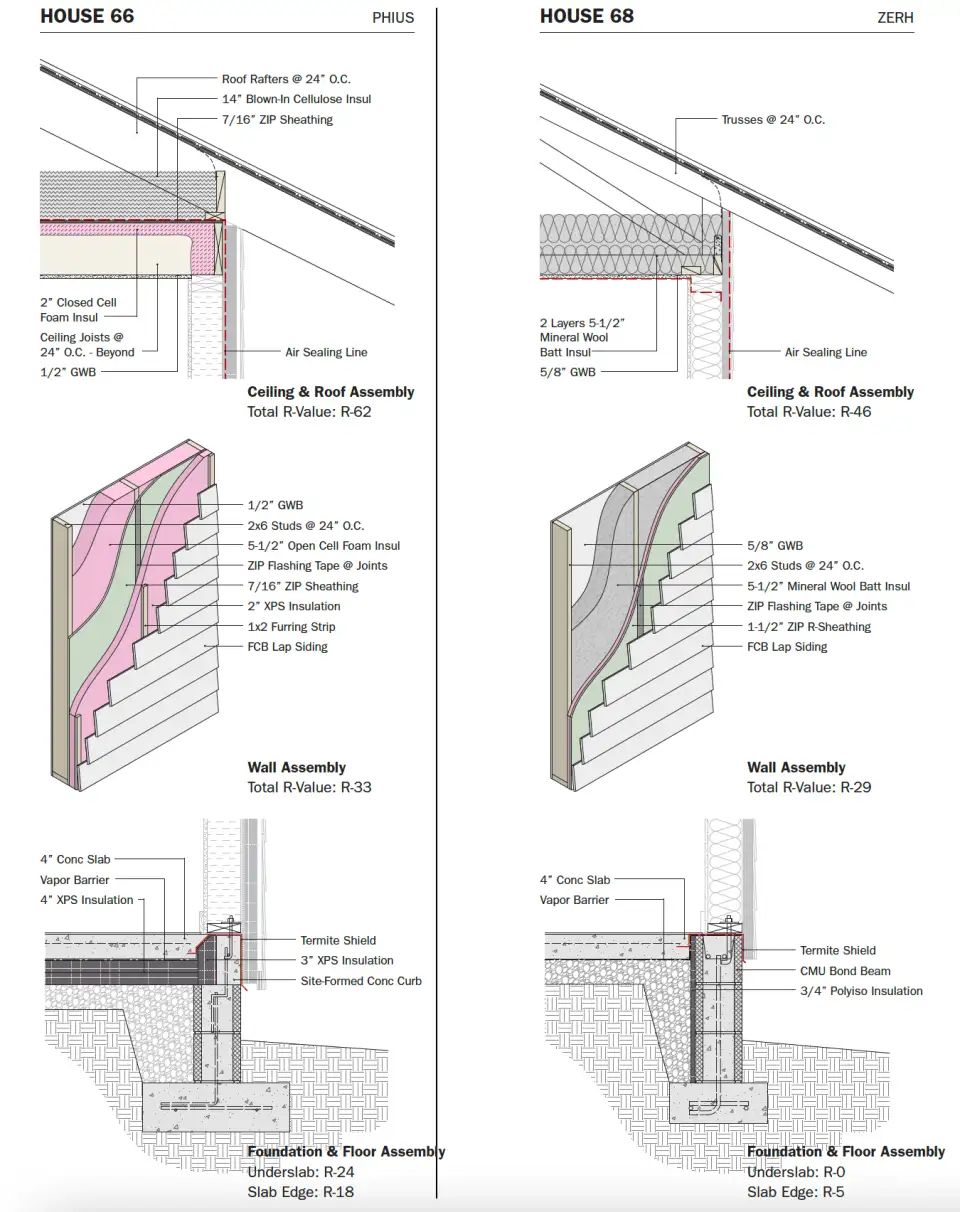

To avoid foundation energy transfers and comply with Phius standards, 4 inches of extruded polystyrene (XPS) was installed under the slab and 2 inches of XPS was used to isolate the slab edge from the foundation wall (see Fig. 1). For the wall assembly, ZIP sheathing was used as the primary air barrier with 2 inches of XPS attached outside of the sheathing, while open-cell spray foam was used to fill in the 2x6 wall stud cavities. As Figure 1 shows, this was followed by vertical furring and fiber cement lap siding to achieve a total R-value of R-33. The ceiling and roof assembly relied on a combination of ZIP sheathing and 14 inches of blown-in cellulose to create an airtight lid separating the ventilated attic from the rest of the home while leaving the ceiling joist cavity open to house ductwork, plumbing lines, and light fixtures. The active systems for the home include Mitsubishi mini-splits, an ERV, a heat pump water heater, and an in-wall dehumidifier, as well as triple-glazed vinyl windows and exterior doors.

The resulting performance was impressive with a HERS rating of 38, and the final blower door test measured an airtightness score of 0.37 ACH50. Excluding costs associated with interior finishes, landscaping, cabinetry, and so on, the final price of the project was $55,438. It should be noted that this figure, as well as the cost figure for House 68, is low because, in addition to excluding the costs mentioned previously, a great deal of the labor was provided by the generous help of volunteers from Habitat for Humanity.

House 68 at a Glance

House 68 took a notably different approach to foundation insulation, as energy modeling showed that under-slab insulation could be eliminated and the amount of insulation at the slab edge could be reduced to ¾ inches of polyisocyanurate given the relative mildness of zone 3 winters. A simplified wall assembly relied on ZIP-R sheathing to provide sheathing and a thermal break in a single step (see Figure 1). To simplify the ceiling and roof assemblies, the team incorporated prefabricated roof trusses and used the gypsum wallboard (GWB) at the ceiling as the top-side air barrier. Following installation of GWB, the installer then air sealed the joint between the GWB and top plate, but this sequencing ultimately proved less efficient and cost-effective, as the GWB installer had to make two trips. Like House 66, the active systems of the home include mini-splits, an ERV, a heat pump water heater, and an in-wall dehumidifier. Unlike House 66, these components were not Phius-listed. The windows, meanwhile, were double-glazed to comply with the ZERH standard.

The drop in performance was notable in the final blower door test; the home scored a 1.76 ACH50, even as it also received an initial HERS rating of 38. That figure was later increased to 40. However, the final price for the ZERH-built home was $44,844, which again is low because various costs associated with finishes and landscaping are excluded from this figure and it doesn’t reflect the value of the volunteer labor.

Questions Answered

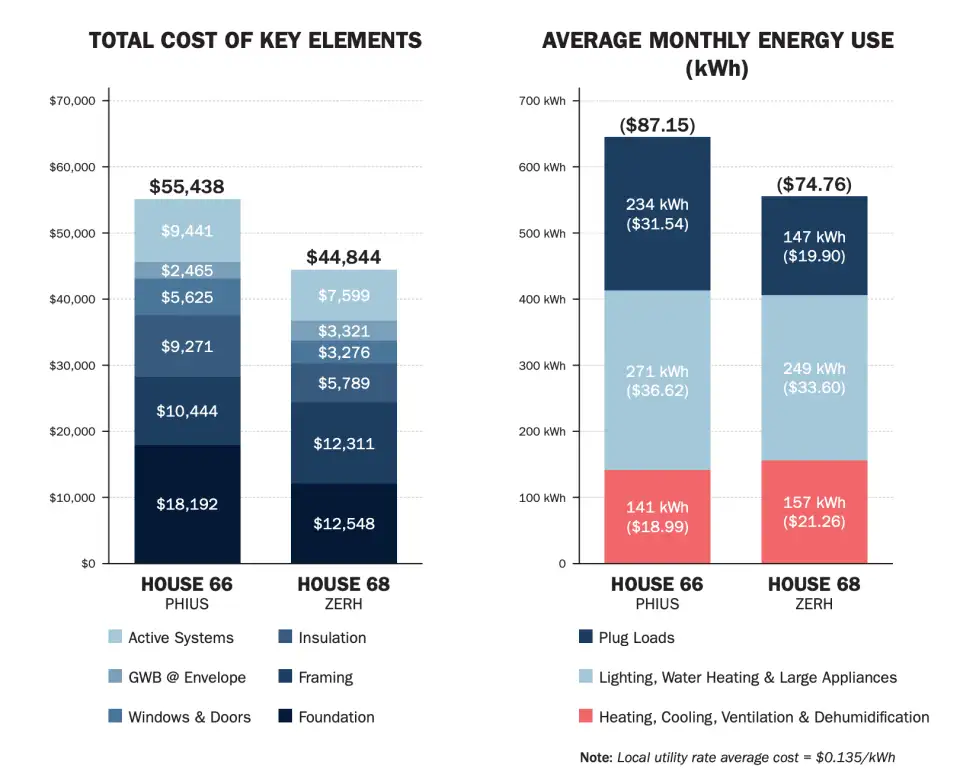

The case study provides an answer to the first question: $10,594 (see Figure 2). Furthermore, the study shows that these costs are primarily associated with House 66’s active systems, doors, windows, and additional insulation (particularly around the foundation). Some of these premiums may decrease as Passive House grows in popularity and a wider selection of high-performance products become available in North American markets. Additionally, as Bruce Kitchell, a recently retired certified Phius+ and HERS rater who was involved in the projects, noted, Phius’ new prescriptive path may also help bring down costs, especially with respect to foundations systems, even though a premium will remain necessary to achieve the level of performance a Passive House demands.

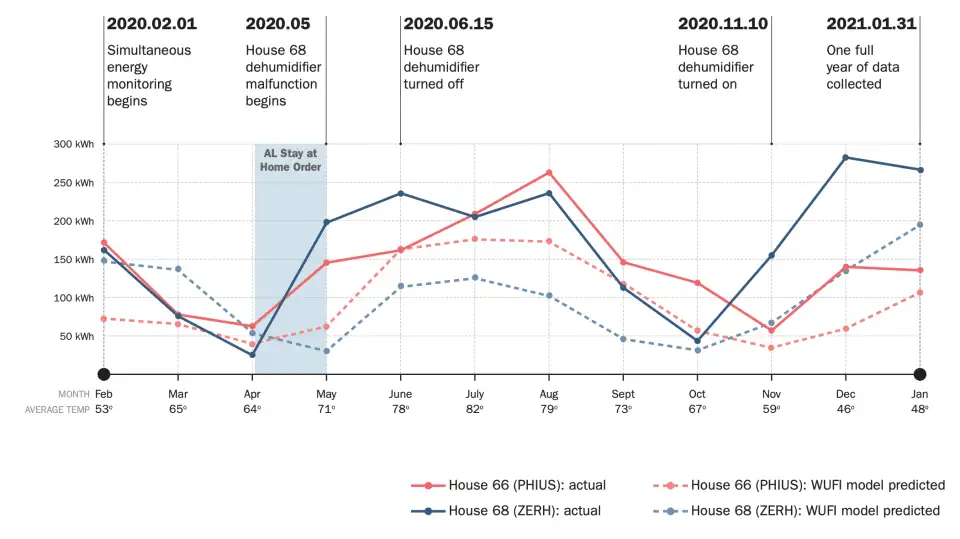

The answer to the second question about the difference in cost to operate both homes is less clear, as monthly energy use between the two homes (plug loads, lighting, and large appliances exempted) is comparable when averaged out over the year (see Figure 3). Both were well under the average monthly cost to heat and cool a similarly sized home in Alabama, which Hinson and Stagg calculated to be around $67. House 66 demonstrated an especially strong performance during more temperate months, as shown in Figure 3, on account of the additional insulation. Of particular note and a possible cause for concern is that both houses performed far worse than models indicated that they would. However, the side-by-side study was initiated in February 2020 and took place during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Pandemic-related behavioral changes could account for the disparity between predicted energy use and actual energy use, as occupants were required to spend far more time in their homes and necessarily used more energy, according to the team. House 68 also experienced a dehumidifier malfunction.

As to the question of how building design affects costs for homeowners, there were some answers. Given that the average monthly energy costs associated with heating, cooling, ventilation, and dehumidification for House 66 was $19, while the average for the state is $67 translates into savings of around $46 per month ($575 per year). However, the cost premiums between a high-performance house and a code-built house will necessarily mean an increase in market-rate mortgage costs. To put this in perspective, the $10,600 cost premium between House 66 and House 68 results in an additional $44.14 per month in market-rate mortgage costs—essentially the same as the monthly operating cost savings.

Despite the cost premium, improvements in indoor air quality and quality of life could produce dividends that offset the difference, though these benefits have not been quantified in this study. Additionally, these premiums could be significantly reduced by state or local programs that provide homeowners with incentives to improve the performance of their homes.

On a larger scale, enabling more homeowners, particularly those in the rural South, to invest in the performance of their homes could make their homes more durable, bring jobs to their local economies, and ultimately help small towns survive. As former U.S. Representative Mike Conway (R-Tex.) noted in an opening statement before a 2017 Committee on Agriculture hearing: “Our shifting population moving out of rural communities into urban and suburban counties, is also shifting the tax base making it difficult for small communities to finance the upgrades they need to continue to be competitive in a modern economy,” he said. “Services are lacking, so families move out. As families move out, the tax base shrinks. And as the tax base shrinks, services must be curtailed and upgrades must be postponed.”

Images, figures, and data courtesy of the Auburn University Rural Studio faculty and staff; the Buster’s House Prototype student design team; House 66 and House 68 student teams (David Hinson and Mike Hosey, as faculty leads); House 66 and 68 faculty, consultant, and AOHFH team; and the data collection team.