Tim McDonald, architect and principal at Onion Flats in Philadelphia, is an innovator who isn’t hesitant to share his expertise and his opinions, good and bad, about his own decisions. The firm has designed and built a series of multifamily Passive House developments in Philadelphia. Each development embodies Onion Flats’ then-current best practices, and usually a series of lessons learned from its previous ones.

Take as an example the 28-unit Bank Flats, which just opened last November in Philadelphia. The rental apartments are mostly 450-ft2 one-bedrooms and 300-ft2 studios. Bank Flats was built with essentially the same superinsulated panels used on Onion Flats’ previous 25-unit Capital Flats2-The Battery project. The same air barrier caulk was applied to each panel edge before the panels were screwed together, forging a very airtight structure. Both developments feature green roofs. In most other aspects, the dissimilarities predominate. The PV system, the windows, and all of the mechanical systems are different—a reflection of experience gained and of the availability of new products.

Both Capital Flats 2‑The Battery and Bank Flats were designed to be net zero. A 77-kW bifacial PV system shading the roof has almost allowed Capital Flats 2‑The Battery to achieve this goal. At Bank Flats the 177-kW PV system doesn’t cover just the roof; the bifacial panels wrap the whole structure. The solar façade is held off from the structure by 24 inches and doubles as a shading device. With this system McDonald projects that the whole building, which has a footprint of 5,200 square feet, will be net positive, producing 20% more energy than the building needs—a goal that wouldn’t have been possible if only the roof were covered.

McDonald has not installed utility submeters for each apartment in Bank Flats, because he considers them a waste of space and money when the monthly per-unit bill is expected to be quite small. He is monitoring each apartment’s electrical use, which will help with commissioning and detecting abnormally high usage. Bank Flats’ rental fees include a monthly fixed charge for electricity use.

Thanks to the prefabricated components, Bank Flats went up in five weeks—and the windows had already been installed. The cooling load turned out to be the defining factor for these window specifications. Although triple-pane windows were used in past projects, for this building McDonald specified double-pane windows with a U‑factor of 0.2, because triple-pane windows would have actually kept too much heat in during summer and swing seasons. The solar heat gain coefficient for the windows is .32, and screens were added that are designed to reflect heat from coming into the building. The double-pane window, the reflective screens, and the use of the PV panels as an effective shading device all helped the project to meet PHIUS requirements for heating and cooling.

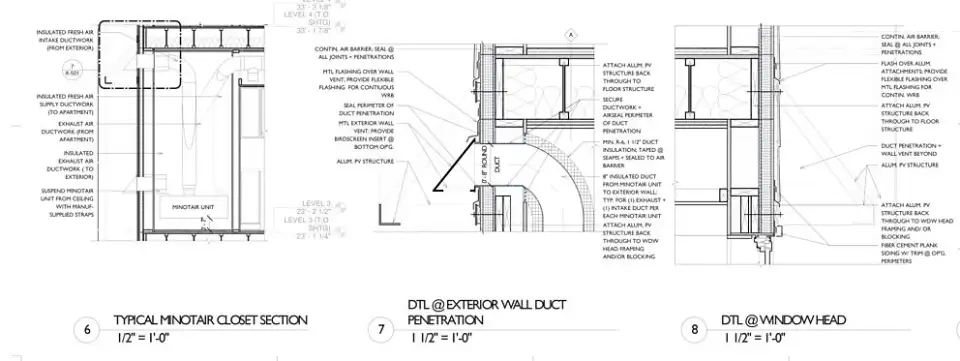

To address these heating, cooling, and dehumidification loads, McDonald chose very quiet, decentralized HVAC units—one for each apartment. Each unit combines energy recovery ventilation with heating, cooling, and dehumidification. In case the heating supply is insufficient for the occasional extremely cold night, McDonald opted to have electric-resistance post heaters installed in line with these units as a backup.

Hot water is the next-biggest load in multifamily buildings. In Capital Flats 2‑The Battery, McDonald had used an open-loop geothermal system that delivered hot water and space heating and cooling. Theoretically that was a very efficient system, but in practice, McDonald concluded that it was too complicated. His lesson learned: “If you can only find one person to give a bid on a system, then there’s only a 50/50 chance of getting it done right.”

For help in finding a simpler way to reduce water heating energy use, McDonald brought in Gary Klein, a national expert on efficient hot water systems. He helped design a semicentralized system using a series of heat pump water heaters that each service six to seven apartments. Klein optimized the hot water runs, cutting piping lengths from an original layout by roughly 50%. He also introduced McDonald to a pipe-in-pipe system where the return loop runs inside the supply loop, reducing the need for pipe insulation by 50% while minimizing heat loss.

Onion Flats’ next project, two 44-unit buildings known as Copper Flats, is currently under construction. The mechanical system approaches will be carried over to this project, but McDonald is working with a new panelization system that will deliver to the site most of the buildings—interior and exterior walls, roofs, and floors. The components will be preinsulated with a wood fiberboard; the windows and doors will be installed; and all mechanical, electrical, and plumbing (MEP) will already be included. “This turnkey approach with ONE subcontractor to deliver the entire building with full MEP reduces construction time on the project by 50% and could be a game changer for Onion Flats’ ability to deliver cost-effective, high-performance market-rate and affordable housing projects,” says McDonald.

As this project is coming together, McDonald is simultaneously working on another way to share his expertise. He and his colleague David Salamon are putting together a High-Performance Affordable Housing Design Manual, a step-by-step series of decision trees about how to build high-performance, net zero multifamily buildings. The manual will guide readers through such nested questions as “Will the building be all electric? If yes, here are the metering decisions you will face. What are the factors affecting the choice of a centralized or decentralized HVAC system?” The manual will also include many practical details, such as how to build a thermally broken threshold that meets ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) requirements.

Currently the manual exists only as a two-hour workshop, and McDonald and Salamon have delivered that workshop to hundreds of interested architects, builders, and developers several times over the past two years. They are exploring grants that would allow them to turn “The Manual” into an open-source PDF document that can be shared with the industry. When completed, it will allow readers to vault right over the moments when McDonald thought, “I’m never going to do that again,” when reviewing what were innovative decisions at the time, and to land squarely on the hard-won lessons.