Case Study 2: Engine 16

Built in the 1880s, Engine 16 was originally a fire station on the East Side of Manhattan. After being decommissioned in the 1960s, the building was converted into a church. By the 2010s, the church was struggling to maintain the aging building. Many of the architectural embellishments and materials that had given the original fire station its charm and unique aesthetic had become worn or had been covered up during remodeling.

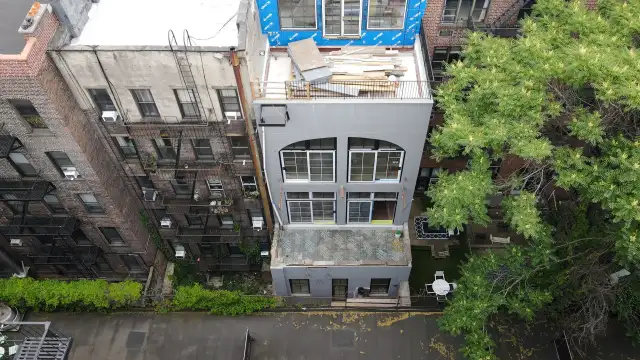

When the building was sold to new owners in 2018, they immediately recognized that they had purchased a diamond in the rough. They engaged Baxt Ingui Architects (now Ingui Architects) to restore the historical features on the interior; preserve the building’s façade; strength its fire resilience; and dramatically improve the building envelope through enhanced air sealing, a more robust insulation layer, and the minimization of thermal breaks. In addition, they wanted to convert the building into a mixed-use, multifamily building with two additional stories on top of the existing structure.

It should be noted that compliance with Local Law 97 was not a consideration when discussing performance improvements, as the addition brought the total square footage to around 13,000 ft2, and the ordinance only places emission limits on buildings over 25,000 square feet. Instead, the owners were motivated by the idea of creating a comfortable space and lowering utility bills through improved systems efficiency.

Compliance with Local Law 126 did help influence the materials used in the exterior wall assembly on the rear façade. Implemented in November 2022, Local Law 126 puts significant restrictions on the use of foam plastics while placing more stringent fire blocking requirements on EIFS. The law mandates fire-blocking with non-combustible materials in concealed spaces within exterior wall coverings. As the rear façade was in a state of disrepair and needed a new exterior finish, using EIFS with ROCKWOOL stone wool offered an almost turn-key solution to the issue while also providing additional R-values and ensuring compliance with Local Law 126. However, EIFS were not applicable on the other walls because it shares a party wall with each of the adjacent properties and the owners wanted to preserve the front façade.

Preservation was a major concern for the owner and balancing the need to protect the historic elements of the building while bulking up the envelope was a challenge for several reasons. Chief among them was the issue of moisture management. Adding more insulation and barriers to any wall assembly can impact the movement of moisture. For older buildings that were designed to allow moisture to freely diffuse through the walls, these new barriers and disruptions in the flow of moisture can compromise the integrity of the brick.

A careful analysis showed that ROCKWOOL’s Frontrock stone wool insulation on the interior side of the masonry would allow better vapor permeability when compared with other insulating materials, meaning that any moisture intrusion would be allowed dry on the inside or the outside of the assembly, thereby helping to preserve the brick. This strategy allowed the owners to preserve and restore the front façade of the building.

Lessons Learned

As these two case studies show, EIFS that incorporate ROCKWOOL products can resolve major design and compliance challenges during retrofits. They can also be used in new construction to help design teams overcome similar challenges, whether they are building in WUI areas, major cities, or anywhere where there’s a demand for comfortable, durable, and fire-resilient homes.