On the gradient between splashy and subtle Passive House projects, Blackstone Apartments, a 19-unit affordable housing development in Portland, Maine, falls so far toward the subtle end as to fall off the graph completely. “We did not discuss Passive House with the client,” says Jesse Thompson of Kaplan Thompson Architects. “Passive House was never a project goal, but the project should be able to meet the PHIUS metrics.” The property owner found out that the project was likely Passive House compliant only after the final blower door test.

“Early-stage, high-profile Passive House projects often launch with integrated teams, lots of fanfare, and extensive lists of consultants,” notes Thompson. For many projects, though, that approach isn’t realistic. Kaplan Thompson Architects has been pushing the envelope on its recent projects, exploring the question: How do we take Passive House strategies to mainstream multifamily construction when the budget doesn’t allow for extra consultants or pretty much extra anything? Or when the owner perceives Passive House as a luxury good?

When working within a constrained budget, the firm strives to prioritize the most critical Passive House elements, balancing improved ventilation, airtightness, and insulation in order to make the best possible building. For this project, Thompson pushed the team on airtightness and ventilation, while keeping a low profile on insulation specifications. “Our multifamily work has shown us the effectiveness of having at least 85% efficient ventilation,” he says, “which does more than a foot of insulation.” Besides, he adds, developers have had decades of experience at cutting back on insulation to shrink project costs, so they’re very skilled at it.

High-quality airtightness, on the other hand, is still a novelty and, more importantly, can be accomplished without raising costs, if it is designed in right. If it doesn’t cost extra, it’s not likely to be cut. Thompson had two advantages in this arena. Firstly, his own Passive House experience allowed him to draw details that he knew the building contractor could successfully implement. Secondly, in Maine all affordable housing already has to meet an airtightness requirement, albeit one that is 5 times leakier than PHIUS’s. The builder was familiar with this type of requirement and was confident the team could meet the specification of .05 CFM50 per square foot. No mention was ever made that this was a Passive House goal, which contractors tend to think of as difficult to achieve and therefore worth raising bid prices over.

The buildable air-sealing details that Thompson specified for the Blackstone Apartments started with a thick vapor barrier under the slab. Nothing unusual there. Subslab insulation—in this case 3 inches—is also fairly routine. The wall assembly includes a nailbase sheathing adhered exterior to the studs and air sealed from the outside with the manufacturer’s proprietary tape. “We could inspect this from the outside and easily see any spots that were missed,” says Thompson.

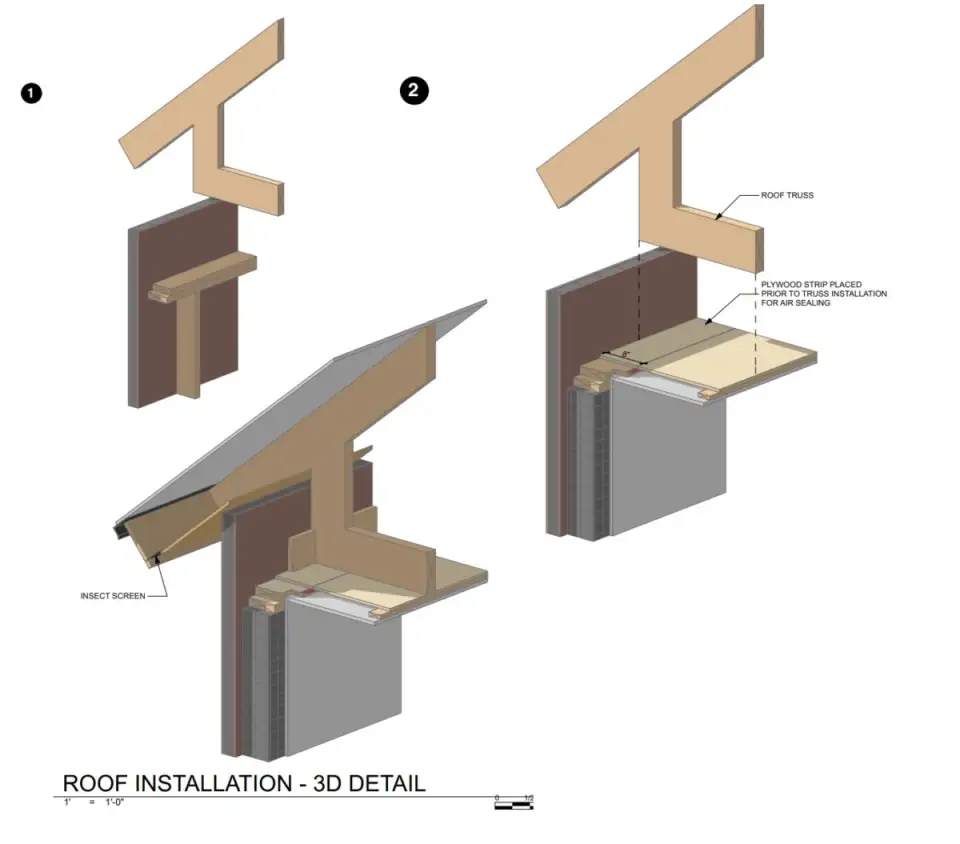

The airtightness layer in the roof assembly was a proprietary sheathing installed under the roof trusses and then taped from the inside. Although this approach was new to the builder, it wasn’t a big stretch, and the panels’ advantages were evident. They provided a hard surface that subcontractors could walk around on without damaging it. Once the wiring and plumbing chases were installed, blown-in cellulose filled and insulated the attic spaces.

The windows are standard casement types with vinyl frames and are triple-pane. Locally manufactured, they have an overall U‑value of 0.22—not rock star performers but good enough, and they survived the value engineering process. The solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC) was also midrange; higher SHGC glazing can easily lead to overheating in multifamily projects.

Ventilation dominates heat loss in multifamily buildings, according to Thompson, because the requirement to deliver 50 CFM to each of 19 units adds up to a big wind blowing through the building all day long. Thompson chose two centralized HRVs with an 85% heat recovery efficiency, one for each of the two floors.

Supplemental heating and cooling is being supplied by heat pumps, with one head in each unit and only two evaporator units on the exterior. The building’s only gas appliance is the hot water boiler, designed with an efficient distribution loop that includes smart recirculation pumps controlled by timers and a thermostat. As the housing is intended for seniors, the hot water demand tends to be lower than it would be for the general population.

Thompson told the developers at the end of construction that the project had met PHIUS’s metrics— while staying within its stated budget of $180 per square foot. “They were surprised and excited,” he says. Kaplan Thompson Architects’ achievement refutes the sometimes-expressed concern that Passive House is a boutique program.