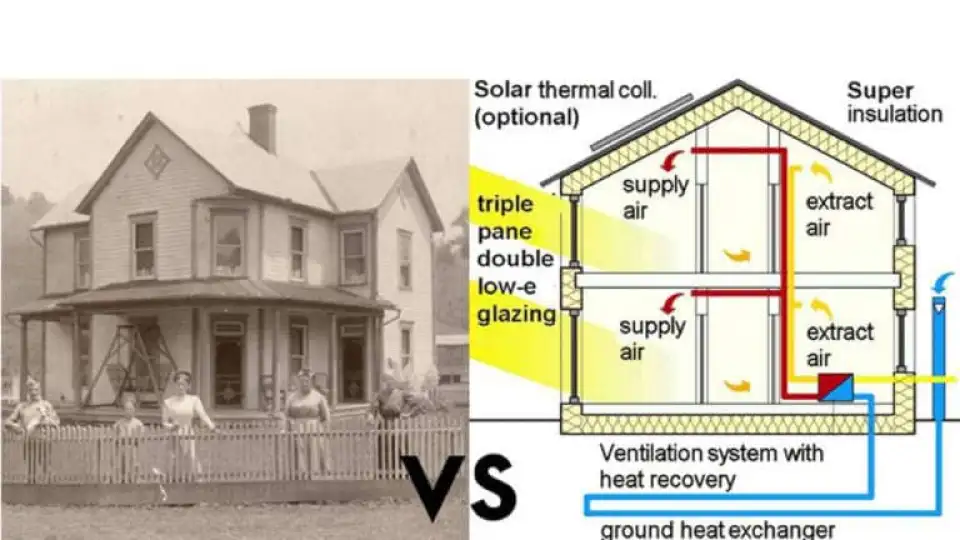

Image above: Grandma’s house vs Passive House

Ten years ago I wrote my first major post about Passivhaus, starting with:

“There are a lot of architects using passive design, but when it comes to building a truly green, healthy house, there is nothing on earth like the Passivhaus. Through careful design, quality windows and a huge amount of insulation, these houses need almost no heat at all. It’s big in Europe and it is coming to America in style.”

And what a decade it has been since then! Hardly anyone is confusing passive design and Passive House anymore, and Americans love Passivhaus so much that one standard wasn’t enough to satisfy them, they needed two.

My thinking about sustainable design, and about Passivhaus, had changed radically over the past decade. I used to be a real traditionalist, believing that we had to learn from old buildings designed before the thermostat age, with thick walls for thermal mass, cross-ventilation, careful shading and trees, lots of trees. Air conditioning was evil and natural gas was the cleanest fuel. I preferred Grandma’s house to Passive House.

But then I was spoiled, and lived in a nice 100 year old detached brick house in a streetcar suburb with a big maple tree shading me. This doesn’t scale, and doesn’t even work anymore in a changing climate; the tree is gone, hit by lightning in a freak storm, and the nights aren’t as cool as they used to be. Also, our understanding of the issues changed.

A decade ago, our biggest problem seemed to be Peak Oil; Passivhaus looked great because it dramatically reduced energy consumption. They even pitched this on Passipedia:

“Passive Houses are eco-friendly by definition: They use extremely little primary energy, leaving sufficient energy resources for all future generations without causing any environmental damage.”

That’s not anybody’s definition of eco-friendly today, we are not worried about leaving sufficient resources for future generations, we want to leave them in the ground. We don’t even talk about energy anymore; we have decoupled it from carbon.

Now, the most important issue is the Climate Emergency, the crisis formerly known by the milder term Global Warming. Now we know that we have to dramatically cut our greenhouse gas emissions right now, and keep cutting them so that they are almost 50 percent less by 2030 if we are going to keep the temperature rise under 1.5 degrees. When it comes to the building industry, the best way to achieve this is Passivhaus.

In the last ten years we have seen global warming change from a concept that might affect our grandchildren to an emergency happening right now. We had Superstorm Sandy. Australia is on fire, incredible heat waves that are making some cities barely habitable. Air quality in our cities is deteriorating again, and we have learned about the dangers of inhaling tiny particulates (PM2.5). We have dramatic pressures on our cities and populations move and migrate; few of my old natural solutions work in this world. It is too extreme, too polluted, too noisy.

Passivhaus, with its airtight construction, looks a lot better from an interior air quality point of view. With power supplies becoming less dependable, the resilience of Passivhaus designs and their ability to keep heat in or out become more attractive. But most importantly, the fact that it is the quickest and surest way to reduce the carbon emissions from our buildings has become the most important attribute.

A few years ago I complained that the Passivhaus standard wasn’t enough. I thought it had to do more, and developed with tongue only slightly in cheek what I called the Elrond Standard, where our buildings have to be 1) Passive House energy efficiency + 2) low embodied energy + 3) non-toxic + 4) walkable.

Dr. Wolfgang Feist, one of the founders of the Passivhaus, was not impressed, and tweeted what I think says we “need to convince as many producers as possible to go for efficiency; no chance to meet goals otherwise.” Three years later I realize that of course, he was mostly right about having to focus on the biggest issue.

The single biggest issue is carbon. Passivhaus is the most effective way of reducing operational carbon emissions. That’s why am saying Passivhaus First.

Other serious experts are still taking the green gizmo route with solar power, batteries and heat pumps; they are all fine. But if you go with the Passivhaus standard, the gizmos are all way smaller and cheaper. The batteries are still too expensive, solar power doesn’t scale vertically, big heat pumps are reservoirs full of refrigerants that are serious greenhouse gases, and we can’t wait until 2030, we have to start now.

It has been a tumultuous decade; so much has changed. Passivhaus has gone from being what one critic described as “a single metric ego-driven enterprise that satisfies the energy nerd’s obsession with btu’s” to what should be the minimum acceptable standard of construction in these times. Most of the critics have been converted or gone into hiding. Instead of being nerdy it’s now recognized as necessary.

Passivhaus First is the best shot we have at decarbonizing in a hurry. It’s not perfect (I think it should measure upfront carbon emissions, and measure carbon emissions instead of energy consumption, but this takes time) but it’s the best we’ve got.