Vancouver is facing an affordability crisis. With housing prices rising faster than income in the British Columbia city, the need for more diversity in housing choices for middle-income households has never been greater. Growing interest in missing middle housing—which includes housing options that range from single-family homes to multifamily towers—has led to an exploration in novel forms of development, particularly in transitional areas that sit between Vancouver’s more vertical downtown and its more horizontal residential neighborhoods to the south and east.

One of these novel housing options is cohousing.

Though the term “cohousing” sounds like branded language from the minds that brought us WeWork, it actually originated in Denmark in the 1960s. Cohousing developments are intentional communities with ownership structures like cooperatives or a homeowner association. Each family or individual lives in their own quarters, but neighbors share and manage community activities. The community also shares common areas, allowing residents to more comfortably occupy less space.

From an engineering perspective, cohousing buildings (like all multifamily buildings) have a lower heat loss form factor than single-family buildings. From a Passive House consultant’s perspective, this means less space is dedicated to insulation and occupants get more habitable space. For developers like Tomo Spaces—which derives its name from a combination of the words “together” and “more” and champions the ideals of affordability, sociability, and sustainability—the concept of cohousing was a starting point for a shared development, Tomo House. As the development is being built for middle-income families, in the walkable and transitional neighborhood of Sunset, and is aiming to reduce energy consumption by pursuing certification from the Passive House Institute, Tomo House will be the embodiment of the organizations’ guiding principles.

Rather than being a quixotic passion project, Tomo House represents a practical solution to some of the difficulties in building cohousing and provides a template that others may replicate. Unlike a traditional cohousing arrangement, in which stakeholders are responsible for overseeing every aspect of development and construction, Tomo House’s stakeholders rely on Tomo Spaces to manage the project—a program described as “Cohousing Lite”.

In typical cohousing developments, delays are a common feature and can dissuade potential cohousing stakeholders. Tomo House has not been immune to delays, especially because the development is being built on a lot that had been previously zoned for two-family dwellings. According to architect Marianne Amodio of Marianne Amodio and Harley Grusko Architects, the developers applied for the rezoning permit approximately five years ago and construction only began in April 2021—and this was a project that the city had been openly supportive of! These kinds of challenges are the reason why Tomo House will be only the third cohousing project to be completed in Vancouver within the last decade when construction wraps in summer of 2023.

Amodio says she shares the developers’ philosophy of affordability, sociability, community, and sustainability, and has appreciated the opportunity to work on a project that offers at least one solution to the missing middle problem. Similarly, she’s excited to be nearing the end of construction on this—her first—Passive House project, which has been overseen by the Haebler Group. “We’re really grateful for their expertise,” Amodio says of the firm. “We’ve learned a lot that we want to apply to the next one,” she adds.

Though Tomo House is also the Haebler Group’s first Passive House, project manager Thomas Haebler notes that they have done what he describes as a few “Passive House lite” projects in the past (meaning they achieved Passive House levels of performance but did not obtain certification) since learning about the performance standard from Scott Kennedy of Cornerstone Architecture several years ago. Haebler has also personally been a Passive House certified builder since 2017 after going through a program at the British Columbia Institute of Technology (BCIT). “I figured, adapt now and adapt early, and it won’t be as much of a shock in the future,” he says pragmatically.

Even if it’s their first, it most certainly will not be their last, as they already have another one under construction. “It’s the way of Vancouver construction,” Haebler says.

Building Tomo

When complete in summer 2023, Tomo House will consist of 12 housing units that range from studios to 3-bedroom apartments and a communal space all situated within the 13,000-ft2 passive envelope. The three-story building is L-shaped, and each unit has views of both the street and the courtyard. The second- and third-story units are accessed by covered walkways that face the courtyard and have balconies that look out to the street, while ground-floor units have direct access to the courtyard. The 1,100-ft2 common space is equipped with a kitchen and laundry facilities that Amodio says can accommodate up to 28 people at once for large meals. Each unit also has its own kitchen should residents want to enjoy a quiet dinner alone.

All units and the common space will be equipped with all-electric appliances (including centralized heat pump water heaters, baseboard heaters, and induction stoves), as well as Zehnder HRV units. In mostly temperate Vancouver, residents will usually be able to cool these spaces simply with cross ventilation. However, there are a few weeks out of the year when the city does become hot enough to justify air conditioning. Rather than install a costly centralized system for such a short peak season, the team instead has provided each unit with a portable AC unit that can plug into a port behind a small access panel. “If they ever get too hot, they can come and open up the panel and hook up a small little air conditioning unit,” Haebler says.

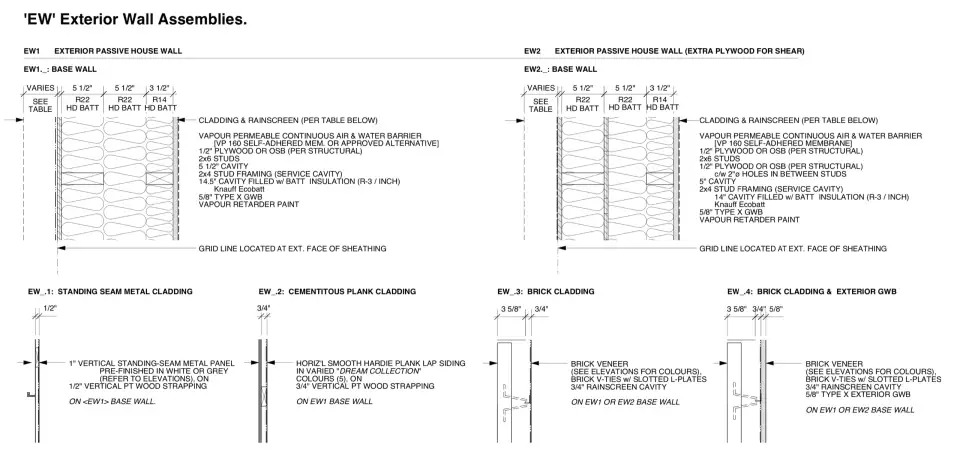

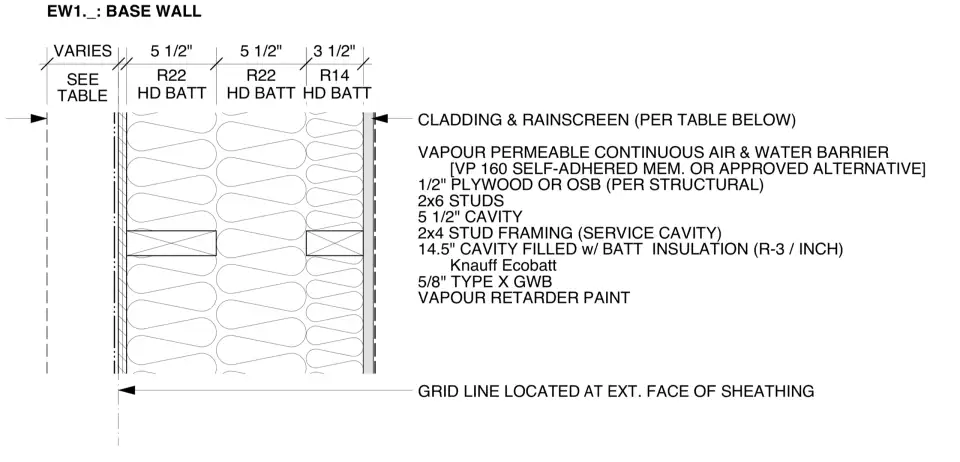

Despite the long wait to obtain permits and begin building, most of the project’s construction has been relatively straightforward. There are 12 inches of insulation beneath the slab on grade, as well as 8 inches of insulation around the perimeter of the pad footings, resulting in an R-value of 96 for the foundation. Haebler says that insulation was not placed beneath the footings, because they needed the support of solid soil. Above grade, the wood-framed walls rely primarily on batt insulation, but also include three additional insulation types—semi-rigid insulation, spray insulation, and rigid insulation on the outboard side—to achieve an R-value of 59. These 2x6 wood-framed wall assemblies are fairly typical locally, but the particular version used here is thicker, consisting of drywall with a painted-on vapor barrier, a 14.5-inch cavity with batt insulation, an AWB membrane supplied by Soprema, and then cladding, which is either brick, metal, or HardiePanel. Some Rockwool was selectively used for fire-stopping and acoustic purposes.

Haebler notes that the project contains a few concrete walls, as well, to provide additional stability. (Vancouver does have significant seismic activity.) These walls contain closed-cell spray foam insulation rather than batt insulation and perform slightly worse than the wood-framed walls, but still have an R-value of 41. Continuous insulation extends up to the roof assembly, which relies primarily on batt insulation to reach an R-value of 81.

Due to the building’s shape, orientation, and space constraints, proper placement of the windows and shading elements was crucial. Haebler notes that they took advantage of the thick walls to set the windows 6 inches in on the east elevation. For the south-facing windows, shading elements were used.

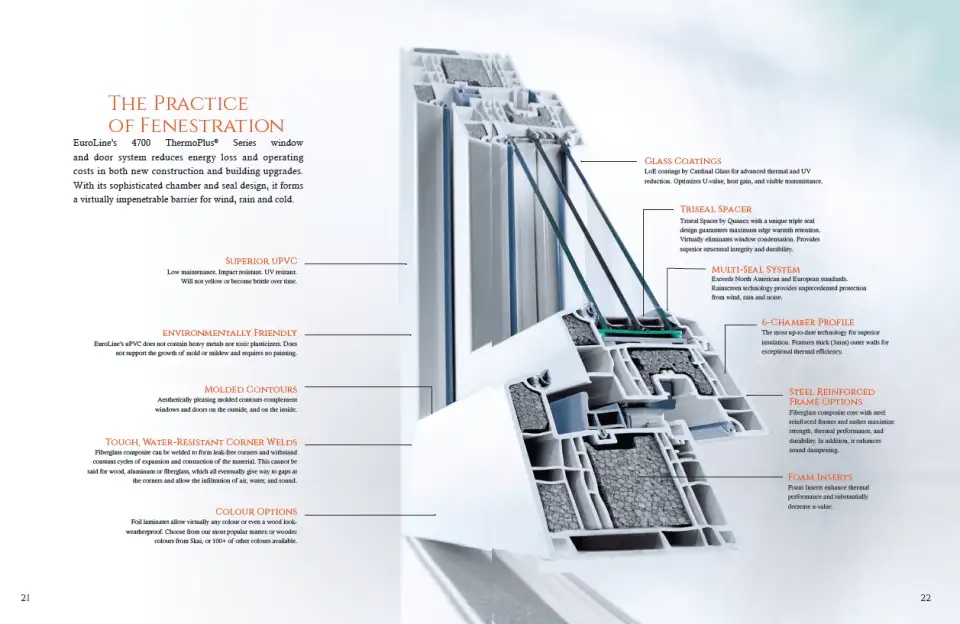

EuroLine Windows supplied the PHI-certified windows and doors for the conditioned spaces and amenities areas. The team decided on the 4700 ThermoPlus Series for its combination of performance (U-value 0.79) and sound proofing. According to Alfred Jury, EuroLine Window’s certified Passive House consultant, the glazing on the balcony door is up to 52mm thick and contains laminated glass to reduce noise pollution from Main Street. “Our typical Passive House window is a very quiet window, but then adding that laminated glass makes it better still,” Jury says. As the glass is still clear, even with the coating, this change did not impact the solar heat gain coefficient.

Installation of the tilt-and-turn windows took careful planning. “We had to take a really close look at our manufacturing process because of the different glass combinations,” he says. “We did probably six or seven iterations of the shop drawings on this project just to get everything really precise, because windows are so key to the performance of the building.”

“As far as how our windows go in, there was a lot of discussion about optimal ‘real time’ performance. There’s a door with a sidelight, for example, so there's a connection between the door and the sidelight that has steel in it and that steel factors into the performance of the overall unit,” Jury explains. “We need to compensate for that with a thicker glass unit, adding more foam in other places of the frame, and ensuring minimal steel just where we need it in specific locations—just where it gives us the strength we need without putting steel continuously through the frame.” Jury adds that these iterations are modeled in Flixo to provide accurate thermal performance numbers of the different frame components.

“The windows and doors are key to the performance of the whole wall assembly and dictate the effective R-value of those walls,” says Jury. Ensuring the perfect fit for each of the exterior walls was crucial to achieve optimal performance without sacrificing available conditioned space. Given that some of the building’s exterior walls will border the sidewalk, there was no wiggle room. “There’s no way in Vancouver that they're taking away an inch from the inside of anybody's unit,” Jury says. “That's expensive real estate!”