If you follow “Passive House twitter”, you’ve probably seen the insightful tweets and SketchUp animations posted by Bryn Davidson, Passive House practitioner from Vancouver, BC, and owner of Lanefab Design/Build. After enjoying one of those animations awhile back, I had the chance to catch up with Bryn to interview him about his approach to projects, his latest Passive House assembly thinking, and how he situates Passive House performance, embodied carbon, and urban design in relationship to climate change and action. Enjoy!

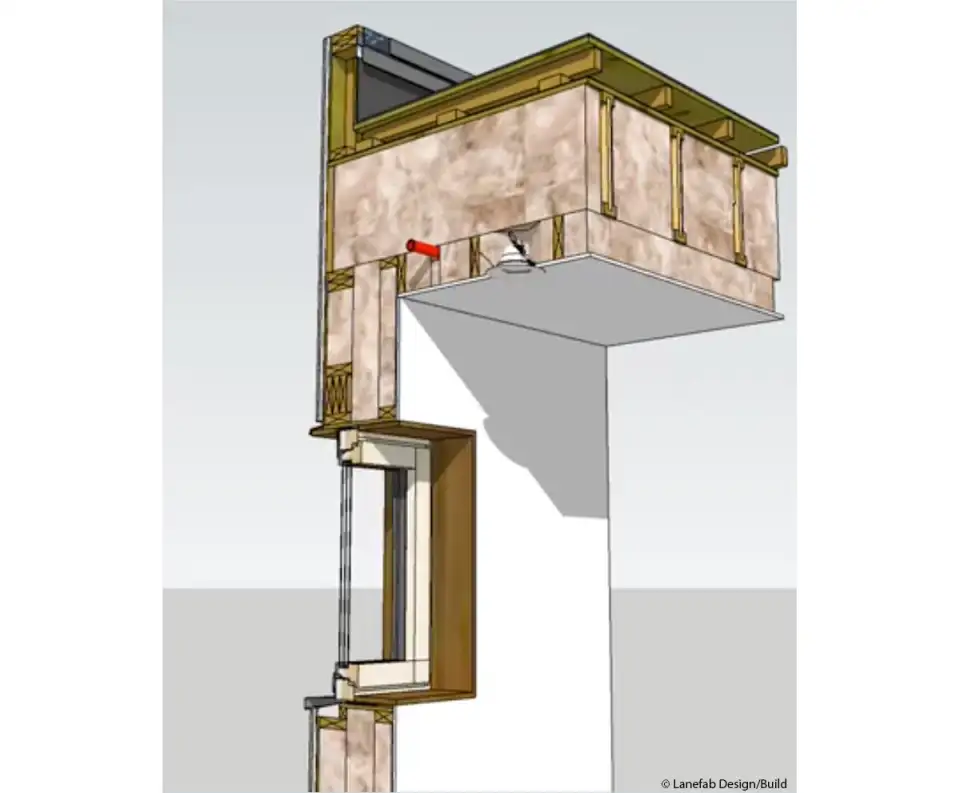

Bryn Davidson: For our single family Passive House projects, we’re typically doing a 17-inch thick wall, and we’re usually aiming for around R‑52 effective in the wall and anywhere from R‑70 to maybe R‑90 in the roof. So, they’re quite thick assemblies. One of the biggest challenges you have with Passive House is achieving a high level of air tightness. You have to look at how your air barrier is contiguous from where the wall meets something like the roof, but also plan the sequence of how it all goes together. That’s why I like doing these sketch-up assembly models because we can get a good sense of, as the guys are actually onsite putting this together, what is the sequence and whether there’s anything weird that you have to be on top of ahead of time. Sometimes in the Passive House world we call it the flappy bits, the little bits of membrane or something that you have to put in early so that you can connect layers later.

For years, we have been using SIP (Structural Insulated Panels), building a two-part wall with SIPs. That’s where the “fab” in Lanefab comes from. We’ve been pretty happy with this approach because we can build a thick-wall project for a cost that’s not that much different from what other builders are doing at code minimum. Our goal has always been to do it on a cost-competitive basis, so we can do a green building on every single project as opposed to doing one “uber-green” project and nine code minimum ones.

So our strategy has always been to figure out not just what’s green, but also what’s affordable and what’s buildable. That’s part of our ethos, and we’ve been able to do that pretty well with SIP panels for a lot of years. Now, going forward, as we get more used to delivering Passive House projects, we start looking at things like embodied energy and some of these second order things that are maybe not as compelling for the typical client, but are an important part of the overall discussion. A few years back I did a TEDx talk about doing net positive projects in the context of climate change. After you’ve done Passive House and after you’ve done walkable infill and you’ve avoided building on greenfield sites, and all those things, the next big step is to look at reducing embodied energy.

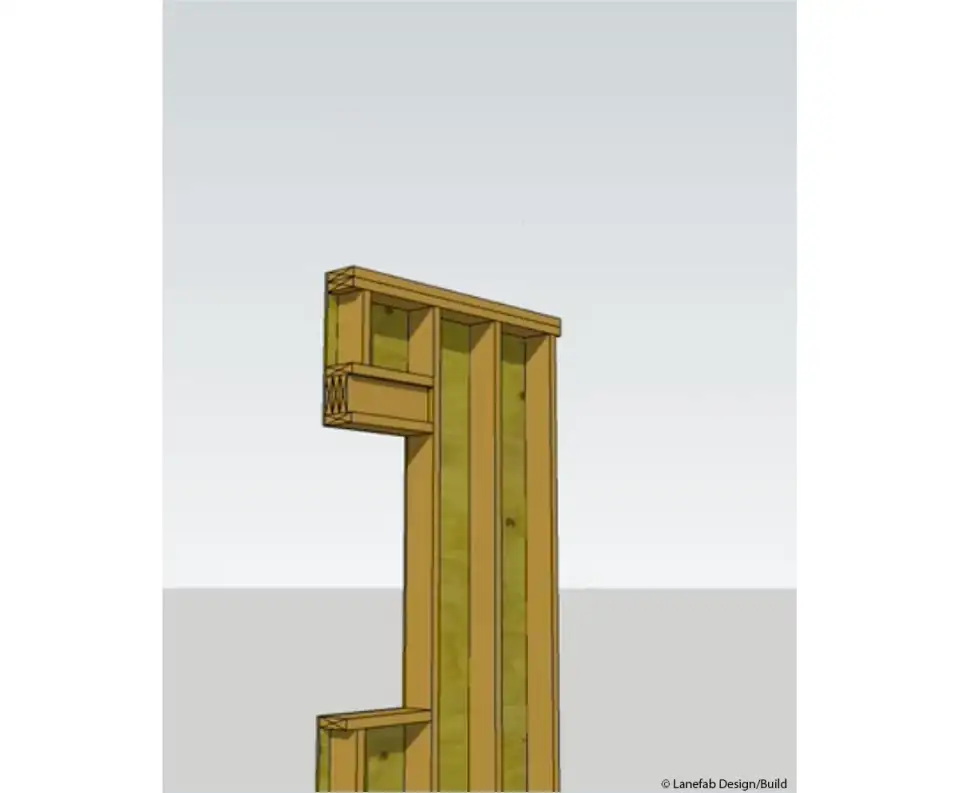

So, in our projects, we’re looking at: Can we have more wood instead of concrete and steel? Can we have different types of insulation? All those kinds of things. Because we’re a design-build practice, we are also interested in doing good design, and we want to have a lot of design flexibility in terms of the types of cladding that we use, the types of articulation, how we do outdoor spaces, etcetera. What we’ve found is that the ideal mix for us is to design an exterior wall that’s structural, and then an interior service wall that’s non-structural.

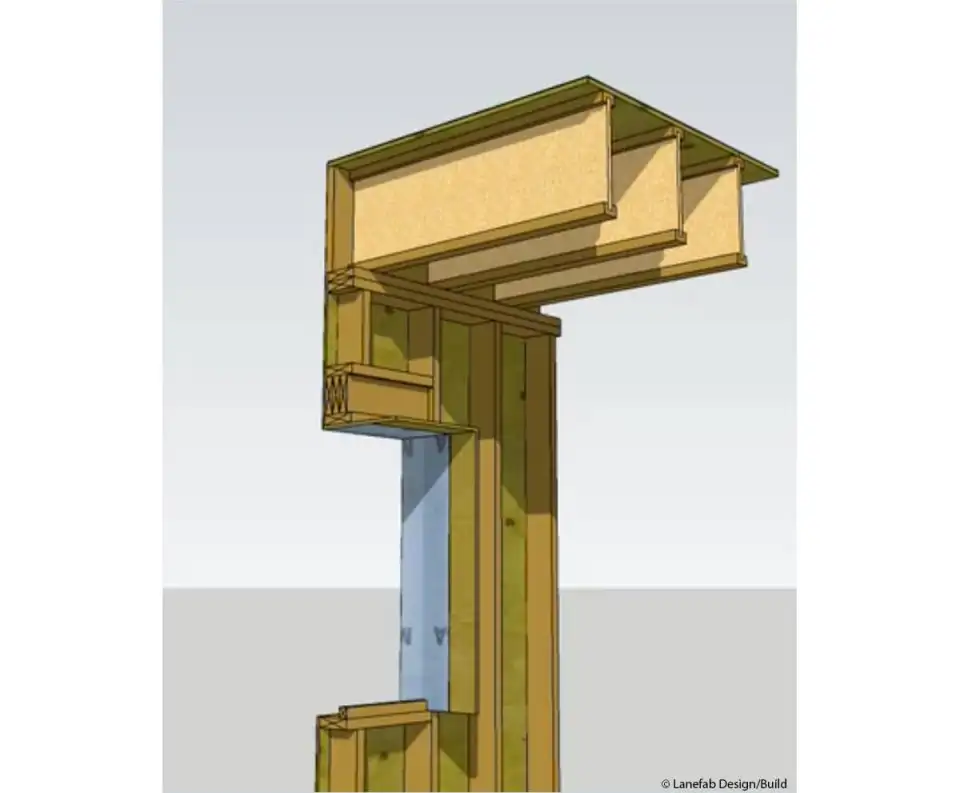

First, that outer structural wall go in:

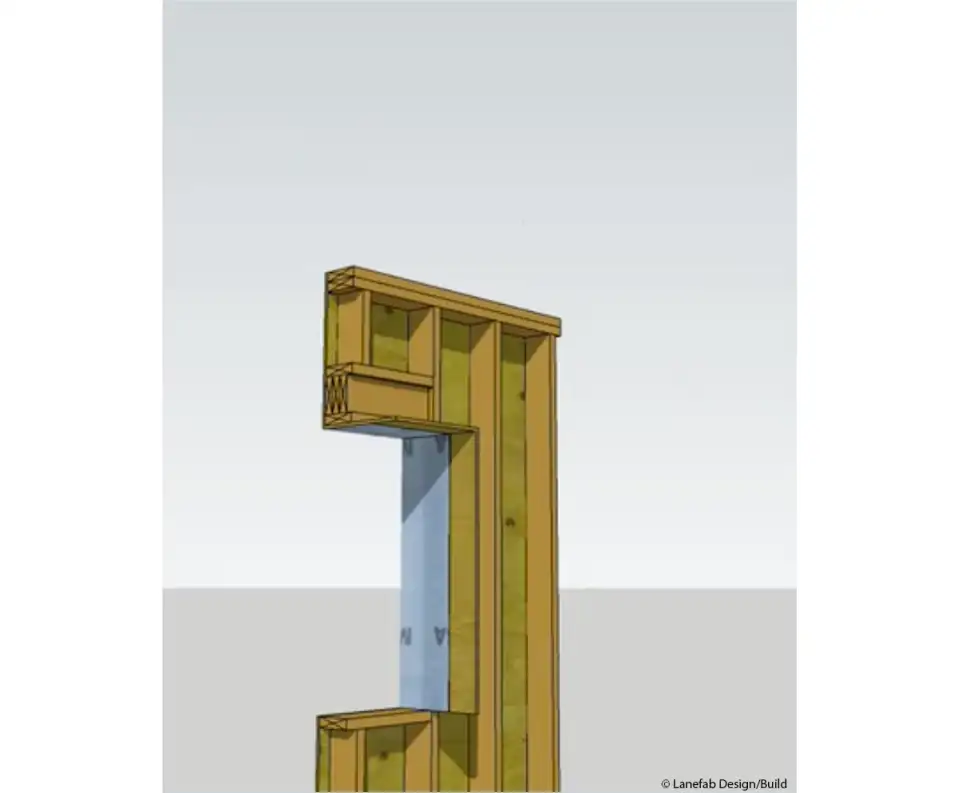

And then after the floor and roof assembly go in:

You just come back in and tack in this inner wall, which is pretty simple:

It’s all very conventional in terms of the types of framing and trades and everything else that are involved.

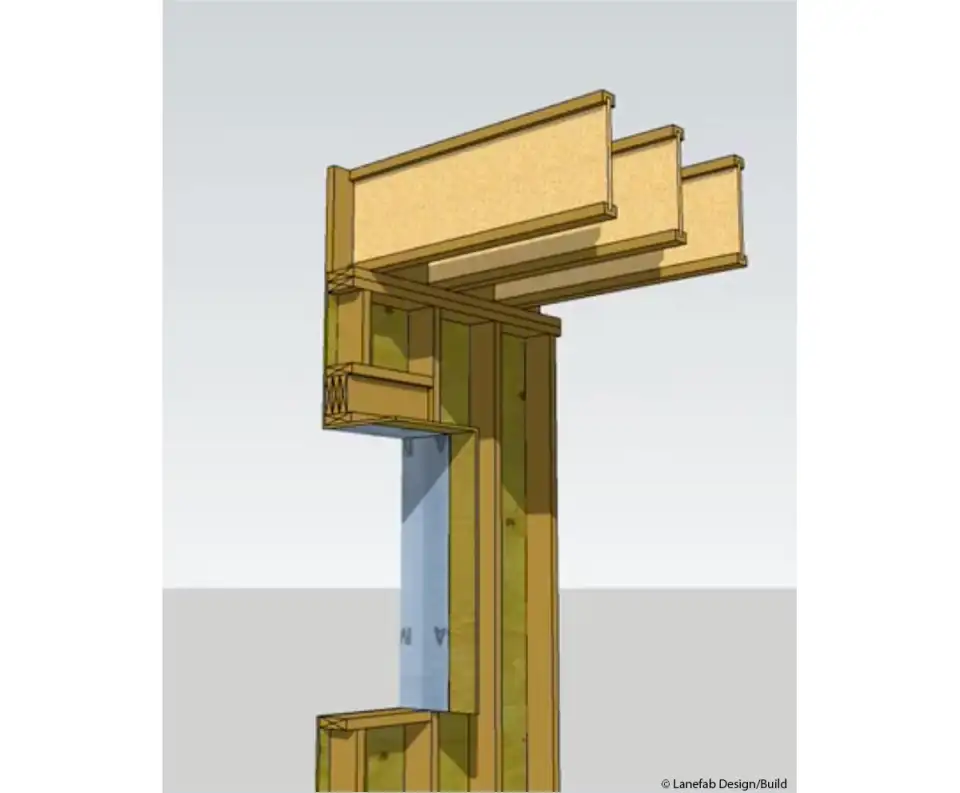

In this particular project, we were looking at an assembly that could use a variety of different types of insulation:

You could do it as blown cellulose; you could do it as wood fiber; you could do it as fiberglass…

But mainly we want the construction to be completely conventional in terms of how foundations are formed, how the walls are framed, and everything else. So what this rendering is showing is basically just a standard 2x6 construction going there, and then a roof assembly, and what we’re doing is wrapping an exterior air barrier—a peel-and-stick membrane—around the outside of that whole thing, and then we put in a bunch of insulation, and then we put vapor barrier paint on the drywall.

The aim with this example is to try and figure out how to make it as simple as possible and as cheap as possible.

Now, there are a lot of folks in town who are using an exterior Roxul approach—putting eight or more inches of insulation on the outside—and that’s a really good system. It has a lot of great benefits, especially if you’re looking primarily just at a wall section. It’s really nice keeping your framing warm and your sheathing warm. The challenge we see is that a lot of times it can be hard to hang really heavy cladding up for these things. Or, if you want to attach outriggers or brackets or balconies or other kinds of things onto the outside, then you end up penetrating through that insulation at each one of those points. So, from our point of view, the exterior structural wall makes it a lot easier. You can attach onto it wherever you need to.

Zack: And it looks like you’re achieving a lot of continuous insulation there between the exterior wall and the interior service wall, right?

Bryn: Yeah. There’s quite a bit there. It’s not even a Larsen truss or something, where you’ve got a bunch of outriggers. This is mostly just continuous insulation between those two walls, and the floor assembly. You can do that a few different ways. You can do a conventional rim joist or use a hanger, and just hang the floor joists on the inside so that the floor joists don’t go all the way to the outside of the wall. Again, in this model we’re keeping it very conventional and just running the roof and floor joists to the outside.

Zack: I appreciate the way that you describe the priorities of buildings and their impact on climate, and how you describe embodied carbon as a second order thing to address. On embodied carbon, what are the key moves that you’re making to reduce embodied carbon?

Bryn: Yeah. It’s interesting with the embodied carbon discussion because there are a lot of folks who get really hung up on foam versus cellulose or something like that, but, frankly, I think it’s not a very interesting part of the conversation. To my mind, the question is: Did you put in a basement or not? Are you doing underground parking or not? Do you have a whole bunch of steel or not? Those are the big design moves that make a big difference. After you get past that, and you’re doing wood frame construction, then you get into these other things—the types of insulation and all this other kind of stuff—but I see those as second order issues.

The other thing is that our supply chains for low carbon products all exist within our larger economy where only a small percentage of things that we buy in our life are actually saving energy. Most of it is just consumption. So, when you contextualize some of this stuff in a bigger conversation, it starts to get a bit nitpicky, but I think it is really important to celebrate those projects that are going above and beyond, and delivering low embodied products because those upfront emissions are really front-loaded compared to the operational savings that happen over a long period of time.

Zack: I think it’s probably fair to say that there’s been something of a blind spot around embodied carbon. But as we become aware of these upfront emissions, how do we avoid throwing energy efficiency out with the bathwater, you know? I think it’s critical to drive home the message that this is a “yes and” conversation as opposed to some sort of “either or” one.

Bryn: With Passive House in general, if we look at examples from say, Belgium, where they’ve been doing it for 15 years and now it’s building code; once you’ve got a local culture of building that’s been doing Passive House for five or ten years, then all of sudden that becomes fairly straightforward, and then you start looking at all the other things you can do. You can bring back all of the architectural diversity, you start looking at materials, and all sorts of other things. That’s where this combination of Passive House and Living Building can point at what that next level of challenges are. Once you’ve figured out how to do an airtight building and deliver it on a cost-effective basis, then you move on to this next tier of challenges.

Zack: That’s a great way to put it. I think that’s a really important insight.

Bryn: At the same time, from my point of view, I’m always pushing the importance of zoning reform. I think that building codes, Passive House, Living Building…that only gets you so far. We need to have walkability. We need to have buildings that don’t require basements. All these things that are coming at us from our zoning that can really make or break a project. When I see a Living Building Challenge project built out in the middle of nowhere, where you have to drive to it, that really drives me nuts. Literally. And so with all of these conversations there’s always further that we could push this. From our point of view, we’ve always prioritized walkable infill and Passive House, and then the embodied energy is the next step that we’re looking at and taking on.

Zack: This is really fantastic. I appreciate it.

Bryn: Thanks for the call, and thanks for your work.

Zack: Absolutely. Likewise!