In this video, Bellingham, Washington is home to the smallest certified Phius project. This tiny Passive House office supports the work of [bundle] design studio, an architecture firm dedicated to high performance design and community involvement. The project served as an educational opportunity for Passive House construction in the community, relied heavily on salvaged materials, and even has a composting toilet. On November 9, founder and principal Dan Welch joined the Construction Tech crew to dive into the details, process, and story of this tiny office.

Dan Welch:

We're excited to share this, the smallest Passive House that's been certified through Phius. My opinion is that this is a pretty simple project, but I don't want to just share the technical information; I really wanted to really share the story behind our project as well, because there's a lot to it and the reasons why we came to some of these solutions and the reason why we pushed some of these Passive House solutions and really tried to get out into the community. So we'll talk about the constraints that led our firm to the conception of the office, how the project moved from conception to reality, how the project is currently used because our world is crazy right now, and then our future plans as well.

This is [bundle] Design Studio. We are a three-person firm. This is actually at a crossover point. Myself on the left, Zach Jorgenson, and then Jordan Frazin who might be on the call today and who is actually leaving our firm to move to the East Coast and do architectural landscape work on the East Coast over in Maine, and then McKenzie Stickney, who I believe is also on the call today or on the video today, as well, and who recently just became a Passive House Consultant and was also part of a podcast with Passive House Accelerator. If you haven't checked that out, make sure that you check out her podcast as well. And this is just we do this as a orientation kind of fun event when we do have new hires out on a little camping cabin that we have out on one of the local islands.

So what does [bundle] do? We are a small, three-person firm. I want to make a plug right here that we really want to become a four-person firm, so if anybody needs a job and is really well versed in Revit and AutoCAD and understands Passive House strategies, please look us up on our website and send me an email and your portfolio, and let's get somebody else working in this field. So this is what we do day in and day out. We don't have million dollar clients. We work for middle-class-ish people, but all of our projects at heart, are Passive House or high performance. At a minimum, we certify everything through Zero Energy Ready Homes. This is one that we just completed last year and it's a low carbon all the way around. This is called the Felicity House.

This is a Passive House, but not certified. The highlights include: cork exterior insulation; dense packed cellulose for all walls, floors, and roofs; Zender HRV; the beautiful juniper siding on the outside, which is reclaimed from Eastern Oregon; Cascadia windows; and all electric appliances. This one also received a Zero Energy Ready Home Home Innovation Award this year.

We also do a lot of renovations. This is a Hawthorne house. This was a whole house, deep energy retrofit. We do a lot of these because we don't have a lot of land in Bellingham left with current zoning. And so we get a lot of folks that purchase a house and want to just completely redo it. We get the opportunity to do the exact same type of Passive House strategies, but in an existing shell. And so this one also this year received a Zero Energy Ready Home Home Innovation award. This one has double stud walls. It's a chainsaw retrofit. So we reframed a new roof on top with extensive air sealing; Zender HRV; the Sanden combi system for air for domestic hot water and radiant heat.

This one's just down the hill. This one was the fourth lowest HERS score through RESNET last year, though kind of a sleeper project for us. Part of that obviously is this massive array that's on top of the roof, but also within the guts of this building we have R13 exterior installations, Zender...the whole nine yards.

So, you can kind of sense a theme on what we do as a firm, but then outside of our Passive House we also do some other work as well. We do some restaurants. We have a coffee shop, Camber, up here and Pure Bliss on the upper right. We also do some historical preservation that also get a lot of our same Passive House strategies. The bottom left was a 1905 Victorian that we did a big addition and restoration to. And so that one again has some double stud walls, higher performance windows, Zender HRV... Everything. And then the bottom right, since we also play a little bit, we have a little bit of public art in Bellingham, Washington. This was a Bellingham hamster wheel. It was a little project that we did to get some of the hamsters out running on that wheel and having a good time. So, that's kind of us in a nutshell. As you can see, we do have a theme. Everything that we do is Passive House based in the strategies, trying to reduce those heat loads and cooling loads and just our overall carbon.

This is the last project I wanted to share outside of the tiny office. This is the house that kind of started it for us. My background was more in public work. I worked for a great little firm in Mount Vernon, Washington, called HKP Architects, but they did more campus buildings. Starting at Bundle, I didn't really have a business card to show people residential work, and so this is a house that kind of started it off for us. This project specifically was designed to Living Building Challenge. We did not achieve Living Building Challenge, but if you look up on Living future's website, there are a few case studies on the house for certain things. This is net positive energy by about 50%, net-zero water. We don't have any sewer or water connection. This was the first building to get the Sanden CO2 combi system in North America, and then we have Zender HRV and Cascadia windows again.

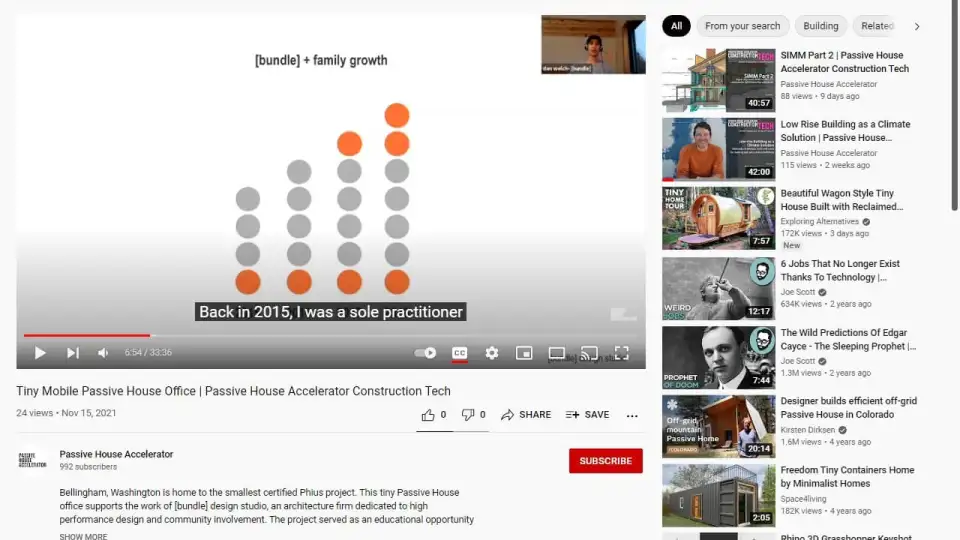

So this one's been very special, but this is also where the story of our tiny office starts. So this is a diagram that starts back in 2015. Back in 2015, I was a sole practitioner working out of the Birch case study house and I had a family of four. I had my wife and two kids. In 2016, the bonus child showed up by surprise and I was still a sole proprietor. But in 2017, the workload off of our Passive House projects really started to take hold and I needed help. That's when I hired Zach Jorgenson. And then in 2018, Jordan Frazin came along as well. As you can see over the years, both family and business has have grown.

This was taken within the Birch case study house, which was the home office. Obviously you can see that as a principal, I got the corner office with a great window, but it was very distracting. It was cramped. We didn't have enough storage between our supplies and my skateboard collection and artwork and such. We needed a place to really separate home life from business life because every day my three kids would come home and it sounded chaotic. It was very disruptive as a firm. It was also very hard to host clients at the house, although it was a great example for us to show the Passive House strategies.

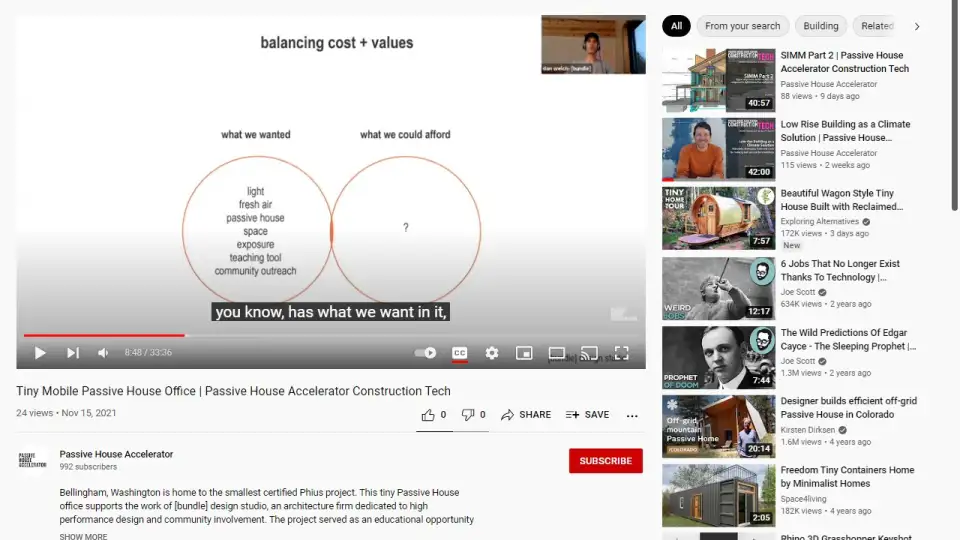

So what do we do? As the same as every other place in the United States, Bellingham is experiencing lots of inflation within the housing market. So where do we go when we need to find a space that has what we want in it, lots of light, fresh air, something that's very efficient, actually more space in our master bedroom, but also allows us to walk the talk when the cost of office space is so expensive, because that's a huge overhead jump for us?

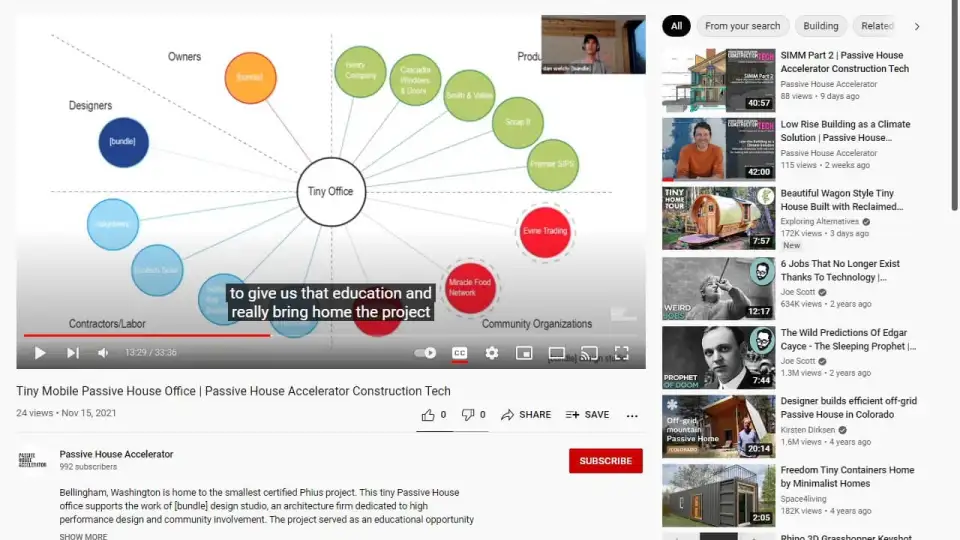

The first thing that we did, not being sure of what our solution would be, is that we reached out to our community. So, at the local green drinks event, we stumbled upon two incredible connections with whom we ended up partnering, Evine Trading and The Miracle Food Network. They're based on the Lummi Reservation, which is just to the west of Bellingham. Together they provide food security for underprivileged families living on the reservation, and they also have huge plans or had huge plans to provide inexpensive, healthy, and safe, tiny homes for those in need of shelter. So there's a lot of addiction problems and a lot of homeless problems out on the reservation, and so these two groups were coming together to try and solve those problems. At the same time, they were also trying to develop some workforce training, to lift up some of those people so that they could afford their own housing and not have to rely on some of the charities that these organizations provide.

The problem is that Evine Trading and Miracle Food Network had zero construction experience. They didn't know how to put a building together. And so that's where we came into the mix. This is basically what they were hoping to accomplish out there. It was bed-in-a-box-type tiny homes. But again, as I mentioned, they had no construction experience and as part of our partnership with these organizations, they offered two things. They offered a trailer and they offered a warehouse for us to construct the building. The trailer, when it arrived was not exactly what we were expecting. It was rusted, it was bent, it needed new tires, it needed a lift kit so the building would actually clear the tires. There was a lot of things that needed to happen and to make matters more stressful we had approximately one week to build a robust building envelope and pull it off the site. So, we were really nervous that the state of the trailer and the requirements that we had in front of us, were not really going to mesh too well, but in the end, Evine Trading really came through. They fixed up the trailer for us and gave us access to the site so then we could start stockpiling a lot of our materials. Once we had these constraints, now we have a trailer and we have a site, but we need to back up a little bit.

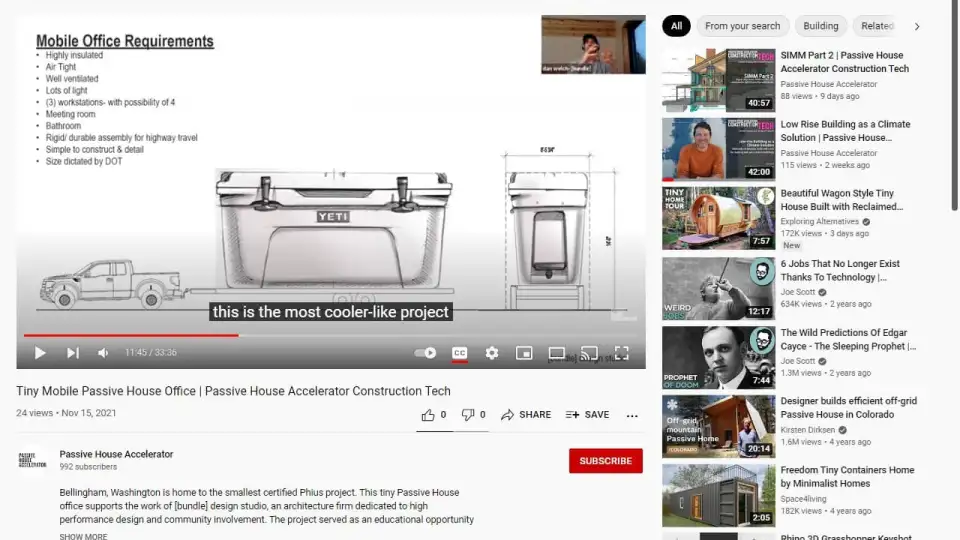

What exactly are we going to build? There were a lot of jokes as we started submitting this to Phius in that this is the most cooler-like project that they had ever seen. It is literally just an extrusion and just solid insulation. But what we needed as an office requirement, was that it needed to be highly insulated, airtight, well ventilated, and have lots of light. We needed to have at least three work stations with the possibility of four, but then we also wanted to have clients in here as well. So we needed a meeting room, a bathroom, and then comes the complication of travel. Most of our buildings are static. They don't experience the same forces as going down the highway, but we also needed a building assembly that was extremely rigid. At the same time, because we're working with organizations that have no construction experience, we needed a very simple construction strategy that was very easy to detail to achieve high performance metrics. And then lastly, as you can see on the very right, the end of view of the cooler, the size is dictated by the Department of Transportation as well.

So we couldn't be more than eight foot six wide, and about 14 feet tall. Otherwise we'd start hitting stoplights and bridges and everything else. So we really had the constraints, the rules of design laid out for us at that point. At the same time, we are a design firm. We are not a construction firm. And so we needed to lean not only on the community organizations that we develop, but we also needed to pull in a lot of our suppliers. We also needed to pull in a lot of our contractors to give us that education and really bring home the project, so that it was cohesive and successful and went together straight. Because again, we're architects; we can draw straight lines, but maybe we can't frame straight. So we partnered with a whole bunch of organizations that you can see here, both in the construction and the product supply, the tiny office design.

We actually had something that we could affordably create a space, which embodied our values. And so from the start, our goal was to create not only a space for ourselves, but also a teaching tool that we could reach out to the community and to our clients. We can showcase the technologies and materials that we use on a day to day basis and we can also show clients some of our go-to strategies easily, as this building would surround them in it. So we could actually touch and feel and show our clients what we were proposing. But then perhaps most importantly, being mobile, also granted us the ability not just to address our clients, but then also go to various events, whether it's a farmer's market on the weekends or large conferences. Being mobile allowed us to pull this trailer to different events, to reach the entire community. And so in that way, one we're providing education, and then on a more self-interested side this is obviously good marketing for us as well.

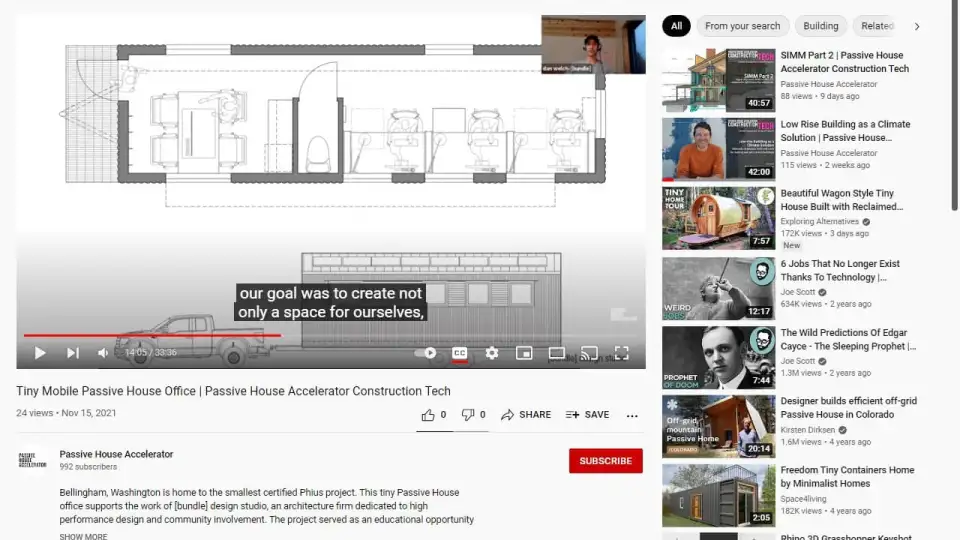

So this on the screen is the plan for the tiny office. It's about a 197 square feet. Again, it's just a straight extrusion. We have a small conference table for four to five seats. We have a small wet bar and a bathroom. And then in the back of house, we have three work stations. It's about 30 feet long, eight feet wide. We tried to keep it eight feet to stick within the standard module of SIP construction, which we'll talk about in a moment.

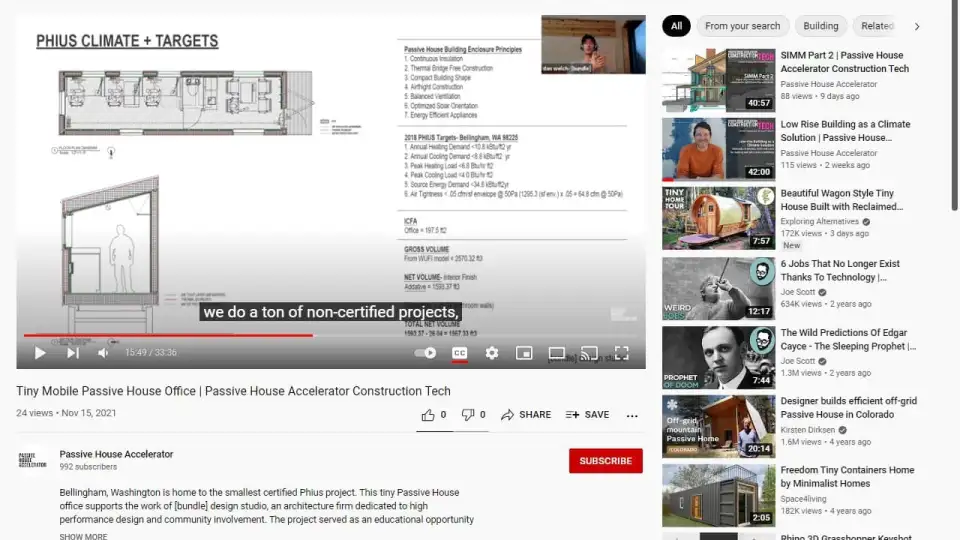

Being able to walk the walk, one thing that was very important to us as Passive House Consultants was that this become a certified Passive House building. We only have one other certified project at this point. We do a ton of non-certified projects, but we really wanted as a firm to make that jump and make it a certified project.

A lot of these, everyone's very familiar with because they're the Passive House building principles. We wanted it to have continuous insulation and be thermal bridge free. There's some of these that don't fit our project exactly because of the space constraints. So compact building shape. We'll talk about form factor in a minute. Airtight construction, balanced ventilation, and solar orientation were all very important to the project. At the same time we really wanted, again, this to be very simple for us to construct and the air sealing details to be very simple, to be successful. You can see on the left-hand side where our airtight layers, our thermal boundaries, and our water protection layers are. They're very continuous all the way around the building. There's very simple insides and outside corners and no articulation within this building other than the windows. So very simple. The 2018 Phius targets, you can see them there. That's what we needed to achieve.

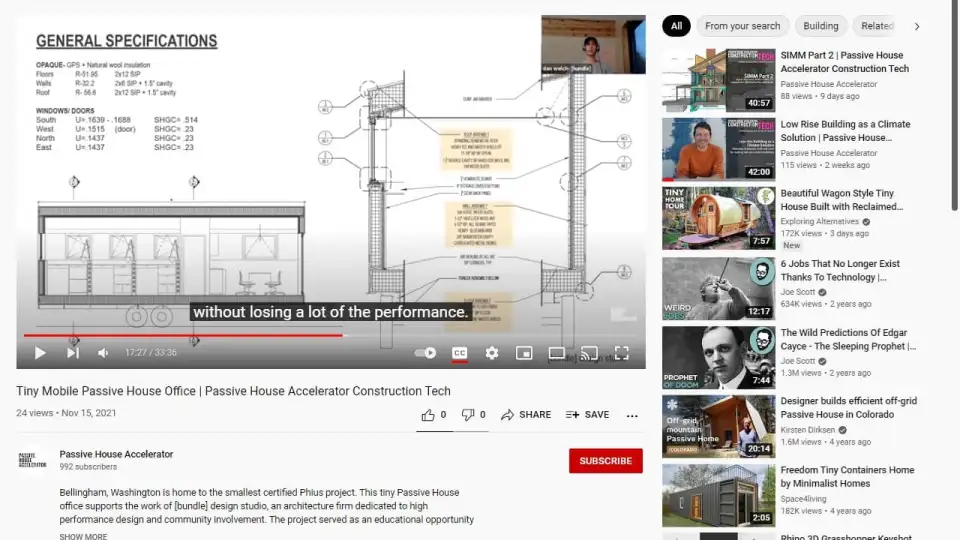

Most importantly, with this small building was number six--that air tightness layer. In the end, we settled on the following specifications. We settled on SIPS because again, we wanted to have something that was extremely rigid, extremely easy to construct, and something that could go down the road without losing a lot of the performance. To be quite honest, we don't use SIPS very often in our firm. We are actually on a mission now because we've become fairly successful at producing high-performance Net Zero Energy buildings and we've kind of moved on to looking at the carbon of our materials as well. So, for most of our materials now, we are attempting to be 100% cellulose-based. So it's not a normal assembly for us, but we still understand that foam products have their place. And this is one of those places that we felt would be most successful. So if you look on the upper left, those are the general specifications for the building: floors around R52, walls around R32, and roof about R56 or R57. To the interior of that on the walls and the ceiling, we also have a service cavity, which is a inch and a half with some Havelock wool in it. And you can see within the wall section there, as well, all the call outs there. But again, this is a very simple construction and we wanted it to be successful for our community partners.

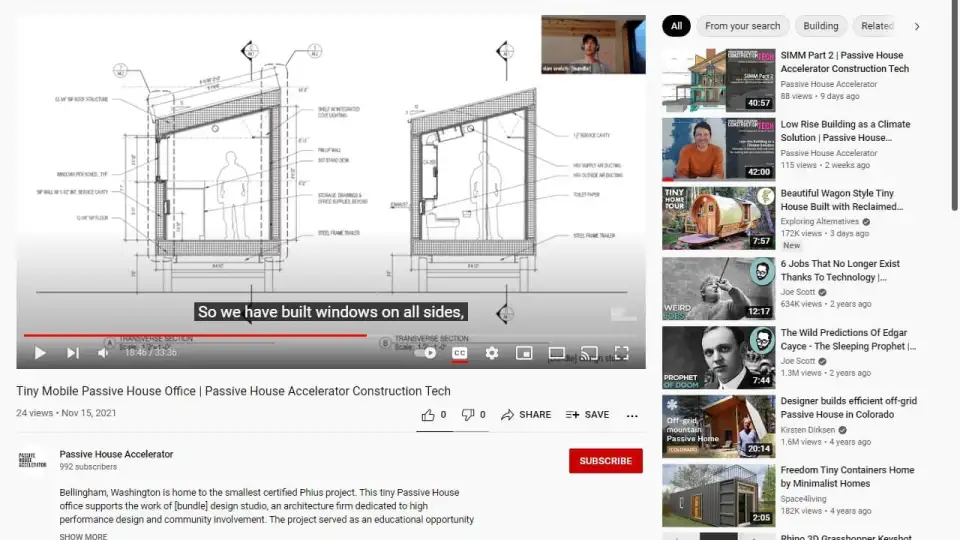

Spatially, working within that DOT constraint, we wanted this to be solar oriented so we have built windows on all sides, but then we focused most of our glazing on the south side. We also went with a simple shed roof for it to be easy to construct, as well as provide a really great canopy for the solar PV system, which would be required to meet that Passive House requirement source energy reduction. And it also worked out really well, just spatially for us as humans in the fact that the wall on the south side was about seven feet. So we have sit/stand desks, so that's about perfect, but then it vaulted out a little bit to give us a little more space on the north where everyone circulates around the building.

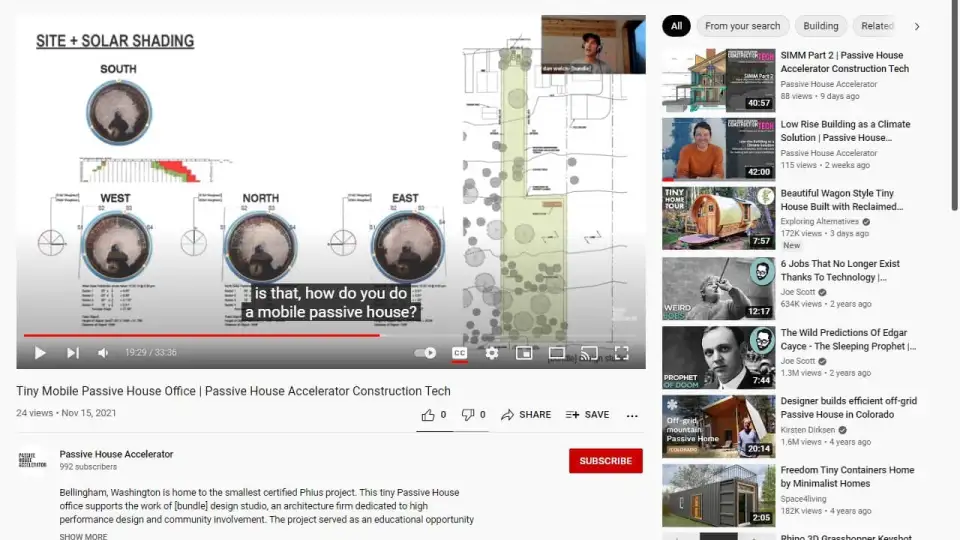

So one of the biggest questions that we get from people is that how do you do a mobile Passive House? Passive House is based in place. And that's a very important characteristic and we completely agree with it. And so this project does have a site. It's not that we are floating out in the ether someplace randomly and be certified. We have a place, a physical location, where are we primarily where this trailer primarily lives. This is in North Bellingham. It's in a neighborhood called Birchwood, which has very unusual lots. A lot of them are 80 by 400 feet long. So they're very unusual. And so you can see from our site studies here and the solar Pathfinder pictures, it's very open to the north and to the east with a lot of lawn. But then further to the south and to the west, we start to gain quite a bit of forest canopy, which actually helped us with some of our solar shading. But the important thing to remember again is being mobile is mobile by name. Passive House is rooted in place, so as soon as we move this off of this site and go to someplace else, it may or may not be Passive House certified. It may be just depending on how we orient it, but the study in and of itself and the practice of Passive House, again, needs to be local and needs to have a specific location.

One of the constraints that we had was ventilation. With this project, some of the intricacies of this is that, again, this is more like an RV. We don't have any water systems. We don't have flush toilets. We don't have sinks in this project. And so it's a little bit unusual, that said we still needed a bathroom within this project. And so one of the constraints that we had was how do we use a composting toilet within a very small space without having obnoxious smells and everything else going on here? Almost every composting toilet that's on the market has really big fans and does a lot of direct exhaust, and that will just immediately kill most Passive Houses, which is why we do recirculating range hoods and so on and so forth.

We couldn't do that with this small space, because as soon as we introduced any direct exhaust ventilation, then we immediately fell out of our specifications and our targets. And so what we did to accomplish this is rather than using a completely balanced HRV system, we unbalanced the HRV system just slightly to provide a positive pressure within the building so that it naturally vents to the composting toilets and pushes all the smells out rather than pulling anything in. And at the same time, we used a very large Zender CA200, which is probably four times too large for this building. But the reason that we did that again is this is an education facility, and we wanted to be able to open the door and show clients what we were going to be putting into their buildings. There's other options that we could have done, but we just felt that was the most appropriate to continue with our education efforts.

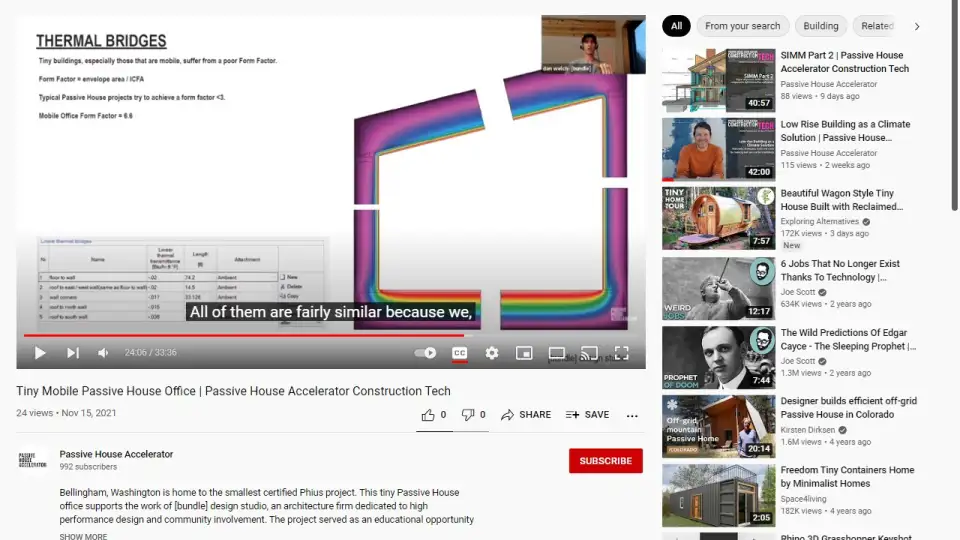

So tiny buildings are special. Tiny buildings are hard. Tiny buildings are very difficult to certify Passive House-wise because they suffer from a poor form factor. So form factor, if you're not familiar with it, is envelope area divided by the conditioned floor area. So, typical Passive Houses try and achieve around three or below for form factor. Obviously, this can range, but that's a good goal to try and achieve. The mobile office, because we have so much square footage for exterior walls in such a small square footage for interior conditioned area, was over twice that, and so that makes it very difficult to control your heat load and your cooling load and your heating demand, because you have so many more surfaces that experience heat loss.

So one of the strategies that we had to use was to count all of our negative thermal bridges. So negative thermal bridges are typically found at the corners, and you can see from our WUFI model here, that we model all of them, all of them are fairly similar because we it's almost the same detail for every single corner of the building, but we had to account for those--otherwise we could not achieve our heating demand and heating loads. And then space conditioning, space conditioning was an interesting constraint, especially being mobile. If this would've been a tiny house that was on a foundation, and we had permanent hookups that would've been completely different, but cause this is a mobile office we didn't know where we were going to take it, where it was going to end up. We needed flexibility within the building.

One of the constraints that we had was how are we going to heat and cool this. Being a Passive House, yes it's going to cycle with the season and cycle with the weather, but we're still going to need to provide some conditioning. At that time, when we were looking, we really wanted to provide a really small mini split. One problem, however, was that there aren't very many 110-volt mini splits on the market. There's a lot more now, but there wasn't at that time. Also at the same time, mini splits are pretty expensive and our loads were so low that a simple little oil heater was really easy to meet all of our demands and still be net-zero. So that was the stance that we went with. For cooling, we don't have a mini split or an air conditioner. Cooling is provided through natural ventilation and night flushing. We never thought that we would need extra cooling, but after the summer, there is some serious thought about needing cooling because Seattle area hit over a hundred degrees this summer. There is talk about changing that as we move along.

Also utilities needed to be flexible. We provided both an opportunity to be plugged into 220, as well as 110, just so that when we're at home, it runs everything like a lot of our HRV and everything runs off 220. We want to provide that. But again, showing up at the farmer's market, they're not going to have a plug for us. So we made sure that it was double plumbed for electricity in two directions.

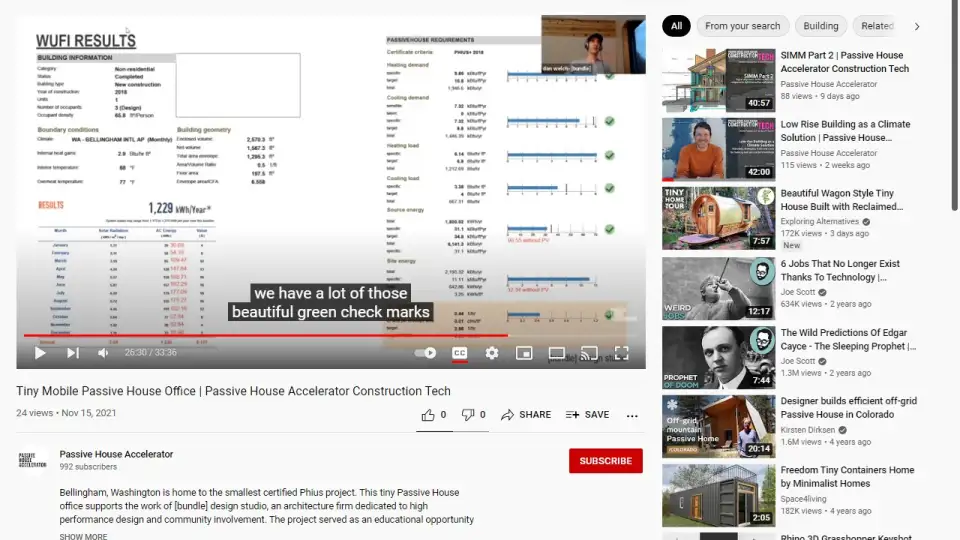

Where did we end up? This is the final WUFI model report. And as you can see on the right hand side, we have a lot of those beautiful green check marks. We met all of the Passive House requirements not with a lot of problem, but we had to pay really close attention to how we were achieving those. One of the things that we really needed to pay attention to was the very bottom right: air tightness. When we are going through the model, if you were to go with the Phius standard of just generic air tightness requirements, it was about 64 CFM that we would need to have for that ACH50. That would not even come close to meeting the Passive House standard in this tiny building if we were to have that, if the building was that leaky. So one of our strategies was to just really go after the air sealing, and being such a simple box we got our air sealing down. The first blower door test that we had was 0.0088 CFM per square foot of envelope area, which sounds crazy because that's eight CFM. But again, that's only 0.44 of ACH 50.We have builder friends who are hitting in the low 0.2's and 0.1s and even lower these days, but the problem is it's a small building and getting it down--again, it's only eight CFM--getting it down any lower was a real chore. So, as is an issue with a lot of Passive House problems, one of the things that we had to include to meet certification was a PV system, so we do have a 1.2 system, just four panels up on the roof, but that was enough to bring our source energy down. And on the left hand side, you can see our solar both in that is from PV watts. You can see both the numbers in black for the AC energy, the kilowatt hours that was anticipated, and then what we received through 2022.

So things have changed over the years a little bit. I don't know if it's global warming or if it's something else, but we're getting a lot more solar in the summer and a lot less in the winter time. And so times are changing a little bit.

Beyond that, I just wanted to share a few of the construction photos on how we put this thing together (see video starting at 29:00). Again, this was, we built the project with the help of some of our contractors, but we were the main contractors for it. Here is Zach and I putting together some of the floor system. We had a sponsorship with Henry Blueskin. That was amazing. They came out and gave a little bit of a tutorial for us, as well as a little bit of a workshop for other contractors, just to show their products off. This is a floor system. Being a trailer, we had to completely waterproof the floor for when it's going down the road. But so again, the floor system is a 2x12 SIP. So that's 11 and a quarter inches of GPS insulation. These are the super splines that go in. This is what makes this building thermal bridge free in most situations. These panels are broken down into about eight-foot sections, but this super spline goes in to tie the two sections together and keep that continuous insulation.

Again, this was a team effort. Most of the building was put together by hand, which was important, not just for us, but for our community partners. The Lummi Reservation organizations were going to try and do a lot of this by hand and didn't have a lot of expensive machinery. Obviously, these are big and heavy, but you can manage to handle it with a group of people. There's a floor system on the trailer that was a huge step for us, but then we did do some machine work. Some of these walls were a full 30-foot long and so obviously we're not going to manhandle those into place, so we did have a forklift for some of the walls. Our air barrier is technically the LSB on the interior, but we did use the blue skin and paid very close attention to all building corners and wrapped that blue skin all the way up and over.

We also paid very close attention to try and bring down that linear heat loss around the window frames as well. So we did both a slope sill out of very dense EPS, as well as EPS on the interior of the windows. And again, air sealing was our saving grace. We just paid extremely close attention to our air sealing. We also had numerous blower door tests. This is Kurt...during our first test, which is when we hit the eight CFM and to the interior. This is the service cavity going in with a lot of our electrical for the workstations. This is an inch and a half service cavity. If you notice the thermal bridges, that we did need to pay attention to were at the corners of the building. That's why our service cavity framing is held back off of the floor and off of the ceiling in those corner areas so that we can wrap that insulation all the way through.

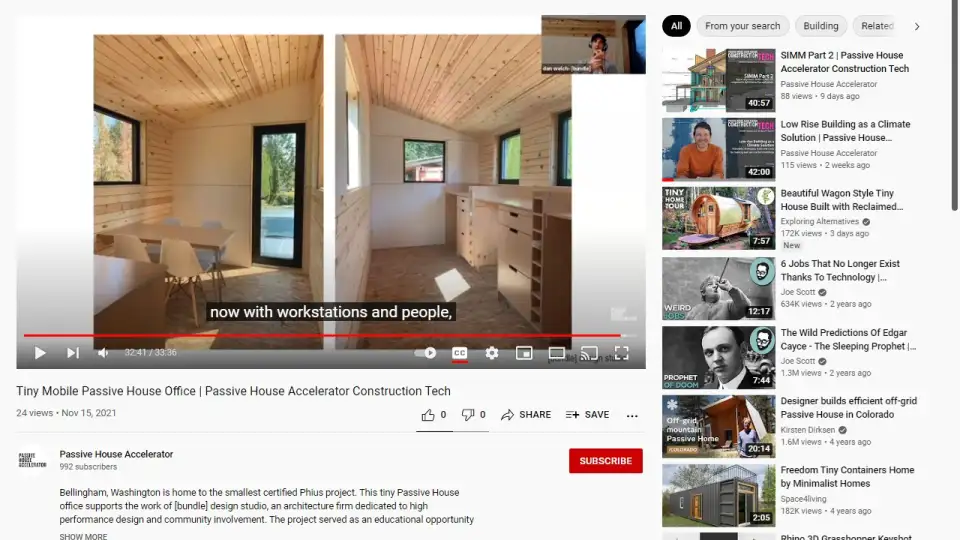

And then again, we wrapped that whole building in blue skin, and then we topped it off with a lot of salvage materials. One, we love salvage materials. We think they're extremely responsible, but at the same time, they're cost effective when you have a whole bunch of them sitting outside there, outside your yard. This is right after we completed. So, this is the finished product. Obviously, there's a little more life to it now with work stations and people, but this is where we're at.

And this is it sitting on its home base site. So as you can see to the east and to the north, lots of lawn and open directly behind us is a lot of more forest. So that's basically what I have for tonight. I'd love to just talk generally about the project. If anybody has questions.