Everyone needs to breath AND eat. Scott Farbman, Innovation Lead at dbHMS, explores ventilation design solutions that provide healthy indoor air and tackles the trickiest indoor pollutants in Passive House buildings, like those from our kitchens. Scott shares individual, semi - central, and central system designs drawing from his research and experience overseeing projects ranging from large-scale mixed-use skyscrapers to small-scale single family homes and community driven libraries. Watch the video above or check out the transcript below.

Scott Farbman:

All right, everyone needs to breathe and eat. That is true. Thanks for having me back. I was on a number of months ago, and it was a great experience and I'm very fortunate and excited to be back and talking to all you lovely folks out there. I think the last I checked we're at like 90 people, which is pretty wild, for me anyway. So thank you for the platform and the audience. So a little about me, I'm an architect by training. A number of years ago, I pivoted more to the consulting engineering world. It just seemed like a better fit for me. I've always loved performance and data and numbers. So I put up my design hat and I took on more of the consulting and advisory role where I found a better fit for myself.

So I'm also a certified Passive House consultant. So I know that there's a split camp out the there, but because PHIUS is local to me in Chicago, that's the direction I ultimately went with my Passive House consultant certification and accreditation. And then lead stuff a number of years ago, just because everyone had to do it at some point to check the box there. Recently promoted to innovation lead. So I really focus on what I see as up and coming in the industry, and trying to keep my studio and my company nimble and quick on their feet so that we could not only stay ahead of things, but adapt to new trends, new technologies, et cetera. And one of my primary goals and passions is to expand our Passive House portfolio, the projects that we work on. And I will get into that a little bit later.

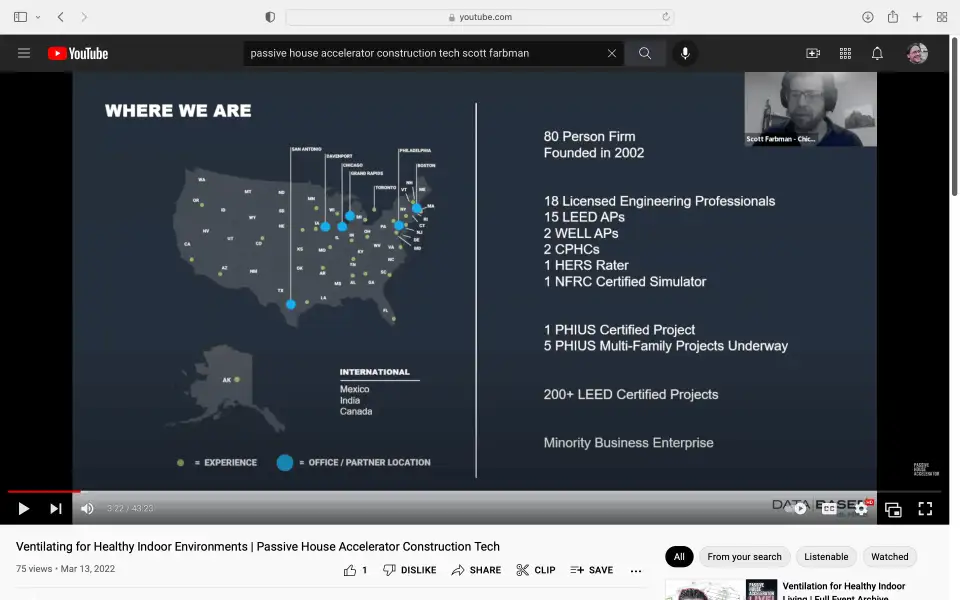

So Shannon mentioned db HMS is our company. We're traditionally an MEP engineering firm, but we have a studio that I'm part of it's called Database Plus. And that's where we do our high performance consulting, energy modeling in sustainability certification. So our primary office is in Chicago, but our commissioning office is out of Grand Rapids in Michigan. We have a couple people down in Texas in San Antonio, and then we have a handful of people in Philadelphia and Boston. Projects really start in the Midwest because we're pretty new, founded in 2002, but we've slowly expanded our reach. We've a good presence on the east coast on the commercial side, and we're starting to get some more projects on the west coast too, which is of course, very exciting. Splattering of expertise here. Licensed engineered professionals, lead APs, couple well APs. We have two Passive House consultants.

We've got HERS rater, and we've got a NRC certified simulator, which is a weird one, but windows are his jam. Pun intended there, I guess. He loves windows and simulating windows, and he's found that when it comes to submittal time from the manufacturer, they're cutting a lot of corners and claiming certain performances that aren't really true in reality. And I'm sure for those of you who have installed windows, you've encountered similar situations. One certified Passive House project in the books. We've got five underway right now, ranging from design to under construction. And then some other stuff, a bunch of lead projects in the likes.

So I think what makes our company really interesting and something that I really enjoy is just the plethora of experience and specializations. On the left hand side here, we've got db HMS, which is our traditional studio, our MEP engineers, and our commissioning folks, which we really came out of lead. So they have a focus on fundamental system commissioning, but they've recently expanded to really high expertise in building enclosures. So, it dovetails with the rater verifier aspect of Passive House. They do a lot of HERS work and a lot of Energy Star work. So a lot of projects go after enterprise green communities. They're involved in those.

And then here on the right hand side Database Plus, which is the studio I'm part of. This is what I think is the fun part of our company, because we get to do all the neat simulation work, whole building energy analyses, net zero energy simulations, feasibilities. Another thing that I'm spearheading right now is carbon footprint and carbon modeling assessment. With all of the heat from IPCC reporting and climate change, really taking a hard look at embodied carbon and what we're putting into our buildings up front is of most importance right now.

So I'm working really hard to expand our abilities to model for carbon. I know PHPP has a plugin for that. There's a lot of really cool stuff I out there, and it's really, really exciting. And then we have a sustainability planning arm that runs a lot of the certification consulting aspects. So traditionally, lead accredited services and got a couple well projects now, which is really exciting. And then of course the past work too.

So got all that stuff out of the way. Can start talking about what everyone's here for, hopefully. In the agenda today is just, because there's some one on one aspect to this and some 300 level aspect, do some general introduction on ventilation, what it is, why we look at it, what our options are. Because I have the opportunity, I'm going to talk a little bit about my at-home indoor air quality experiments, so to say. I'm going to touch a little bit on the design work that we've done to date with Passive House ventilation. And then hopefully, yeah some good time for Q&A. Please like ask any question you want. I'm by no means a ventilation expert, so I'll do the best I can to answer stuff honestly.. I'm sure there's some folks out there who can jump in if I fall short. And really, I like to talk about this stuff. So looking for a lively conversation here at the end.

So why do we need to be ventilating? This is hopefully pretty obvious to everyone. There's the the stat that gets thrown around: 90% of our time is indoors. So most of the things we're exposed to are coming from our indoor environments. I think this is an interesting thing to look at even more so now, I don't know about all you out there, but we've predominantly switched to work from home since early-ish 2020.

So I've been working out of my living space for the last two years, and it has really given me a unique perspective on what it is to really be in a home full-time. Having that fresh air available, love it. Really need it. Being able to control indoor. That's where I'll touch on my experience with what I'm seeing inside my house, which full disclosure is not a Passive House, probably very far from what a Passive House is and should be. But we don't all get the opportunity just yet. And I'm pretty young need to make a little bit more money before I can maybe get that Passive House built for myself and my family. Comfort, always an issue with ventilation and space heating, cooling. And then like Kevin mentioned, reducing health risks, especially respiratory illnesses. That really has come into full picture for me up front. I think that's a really critical issue.

And then of course, on the building durability side, the more airflow you have moving through your house, the better you can mitigate against condensation risk and that material durability issues that everyone hates to deal with. All this stuff kind of dovetails together, material durability and mold, health, everything really, really connected here. So a lot of things to pay attention to.

So what are our concerns? And really, why do we need to be ventilating? I just gave a couple of these slides to a developer that wanted to do gas cooking and no exhaust, which is allowed in Chicago. And I'll get into that later. Hate it to death, but that's just the reality we live in. So combustion cooking has a lot of risks and harms that come with it, and I know that at least me, and I can probably assume for a lot of you out there, we've been kind of preconditioned to think and know that cooking with gas is the best. You got to have a gas range, a 48-inch wide gas range to be that at home chef.

And you maybe paid attention to it a little bit, but people are starting to speak out against that. I think the trend is catching on, but when you're cooking with gas you're putting a lot of bad stuff into your indoor environment, you're putting small particulates, 2.5 mainly, which is the really small particulates that get deep down into your respiratory system. No good. Nitrogen oxide and dioxide, carbon monoxide, of course, which is probably lead the most common thing associated with burning gas in your home. I would say 50/50 chance if you ask someone out there about carbon dioxide in your house, they'll be like, "I have a carbon monoxide detector. I'm good."

So I just think some of these things might be commonplace to us, but the general public level can't differentiate between a lot of these pollutants. And maybe that's not a bad thing, but knowing that there's bad stuff happening, that's what's most important. And then a new one to me, there could be some formaldehyde issues with burning gas. I didn't know that. That's come off some recent research. So because we're potentially putting all this bad stuff into our air, that's why we, from an engineering ethical point of view, really push for proper ventilation and exhaust at any opportunity we have. Passive House or no Passive House, our first recommendation is you have to ventilate an exhaust right or you're potentially liable for some health impacts later.

New research in some recent research. So Rocky Mountain Institute put out a really huge research paper on the impact of gas stoves, specifically looking at elevated nitrogen dioxide. So a pollutant we don't normally talk about, right? In our house. And they're almost always exceeding the indoor guidelines and even outdoor standards for what you want in your space. And then this is a big one. They hard identified that there's a direct correlation to illnesses, and an increased risk with children, which no one wants, right? Asthma, lung infection, and also learning deficits, interestingly enough.

The newest set of researches from Stanford. It came out earlier this year, I want to say maybe January, and they found that methane was the major emitter from gas stoves in an off position. So your stove doesn't even need to be on and it's leaking methane. Not guaranteed, but they found a lot of instances of methane being leaked into your house with your gas stove off, which is wild to me. And then, qualifier here, they said hood use and ventilation are effective in reducing concentrations and nitrogen oxide and other pollutants. So they're saying, "Okay, if you're going to use gas, you have to exhaust and ventilate right or you're exposing yourself to possible risk and harm."

So this is a fun slide. So gas cooking in the headlines. If you follow the news and some of our favorite publication sources, you've probably seen a lot of these. So The Atlantic, kill your gas stove. NPR, we need to talk about your gas stove. The Guardian, gas stove making indoor air five times dirtier than outdoor. Vox, gas stoves can generate unsafe levels of indoor air pollution. And then New York Times, your stove just needs to vent.

This to me is huge because we like to talk about this stuff in our small circle, people who are all on the same page. We could talk it to death and maybe we get a couple people to adopt it because we're so passionate about it. But once it hits the mainstream in the media, people are going to start asking about this sort of thing. I'm sure you all may have clients out there asking about induction cooking, and that's great. And that's really what I want to see. It needs to be driven from the end consumer, if you really want to make substantial change here and get gas out of our new homes and figure out a way to phase it out of our existing homes too.

So what are our options then if we want to ventilate? And Kevin touched on a couple of these. Your older, existing homes out there are probably just relying on infiltration in operable windows to bring in fresh air. Obviously all the research is saying that's not adequate and you're going to have problems. I wish I could do a poll because I would love to know how many people on the call in their home right now don't have any sort of ventilation or exhaust system, mechanical.

The second option is mechanical exhaust only. So fans in your bathroom, maybe a whole house fan, just sucking stuff out, that's it. And then the makeup air is either provided through an operable window, but we all know behavior there. You usually don't have a window open when you need it. You probably have it open when you don't need it. So that makeup air is coming through infiltration, and that's not a good approach especially as construction techniques get better and energy codes progress, enclosure tightness is being required. I mean the threshold there, or spectrum's, pretty wide, but some level of enclosure tightness is being required through energy code. And the tighter homes get the less you can rely on infiltration to be that means of makeup air. And you're pulling air through all those weird nooks and crannies of your wall that, God knows what's in there too. So not my favorite approach.

Third option being mechanical supply only. So I see this every once in a while, you just have a direct supply of fresh air being routed to your furnace, or your return line into your furnace. So anytime your furnace goes on, fresh air can be added to the return and then distributed through your home. That could work. I think a lot of the folks out there know that if you're just pulling raw air from outside, you're losing some energy there because you have to reheat it up. So not the greatest approach. And then the one that we all know and love is balance mechanical ventilation. That's the Passive House method, bring in fresh air continuously, exhaust that same amount of air out, and then recover as much of that heat as you can to keep energy use low and indoor air quality high.

There's a study from Elevate Energy and the Illinois Institute of Technology, it's called the Breathe Easy study, and I'll find a link and I'll throw it in the chat later. But they retrofitted a number of homes in the Chicago area, mostly on the South and West Side, and they did a study where they tried exhaust only, supply only, and then balance ventilation. And in terms of improved indoor air quality and reduced health risks, of course, balance ventilation was the winner, but exhaust only smashed supply only. So supply is the worst of the three. Well, no ventilation is the worst of all. But of the three, supply only doesn't get rid of the bad stuff in your house. It only brings in new air and dilutes. So just an interesting tidbit, and I'll throw that in the chat later.

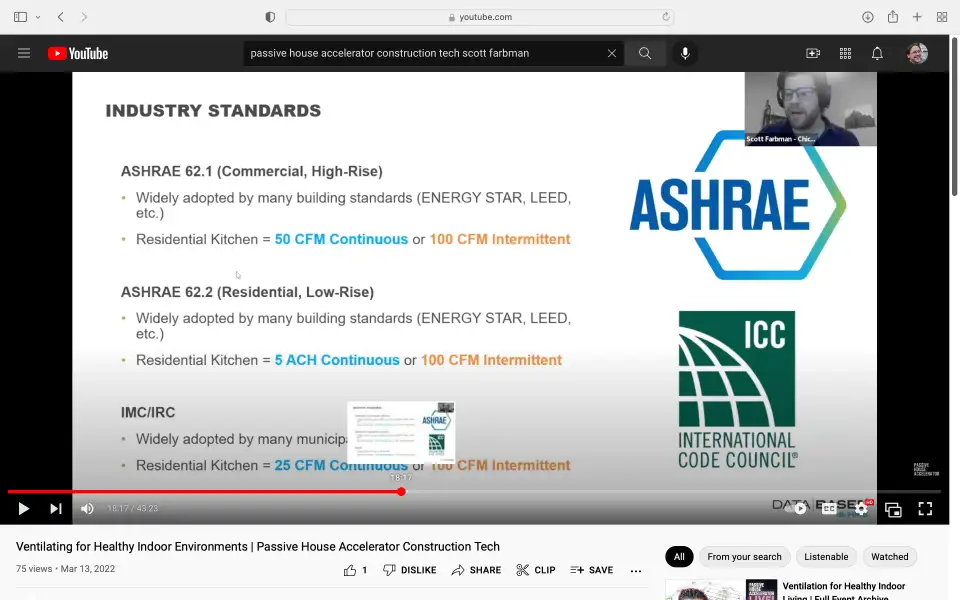

How much time do I have by the way? Because I think I'm a little front heavy right now. Okay, cool. Go quickly through some of this stuff. So industry standards, I thought it's good to throw this in here. So if you're not designing a Passive House, this is likely what you're going to have to design to, at least in the US. If you're in a commercial or a high rise building, you probably are looking at ASHRAE 62.1, and that is 50 CFM continuous, or 100 CFM intermit. So a lot of airflow there. ASHRAE 62.2, which is the residential and below rise guide standard, five air changes per hour in your kitchen, or 100 CFM intermit in your kitchen. And then international code, or the international residential code, this is what aligns most closely to the Passive House requirements. 25 continuous, which is low and nice, or 100 CFM intermittent. So just wanted to frame it a little bit so everyone knows kind of what guidelines are you might be designing to if you're not looking at Passive House.

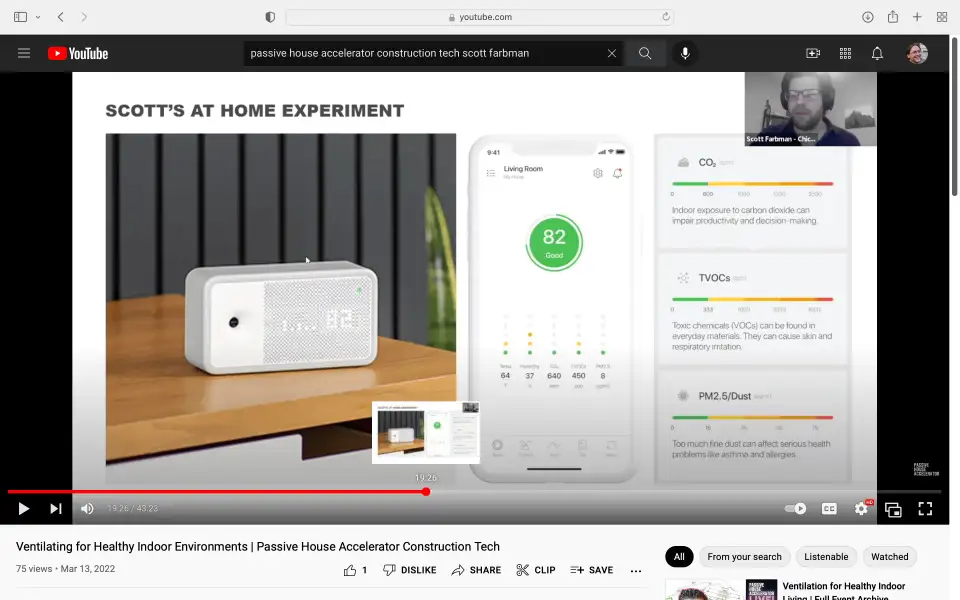

So my at home experience and experiment. I have an Aware Element, which is shown here on the left hand side. I also have a Kaiterra sensor, which is more of a commercial application that I've gotten gifted to me to test out. I like them both for different ways and different reasons, but the user interface, this really is meant for the typical user at home. So this is what I like to point out to everyone. It's got a really nice lead designed UI on your app. It's got your total air quality, and then it's got your individual parameters that you're tracking, and it's got dedicated sensors to pick the stuff up. So dry bulb temperature, relative humidity, carbon dioxide in parts per million, total VOCs, which is a good metric, but a tough metric, and I'll explain why in a minute. And then small particulate, 2.5 here.

So when you're looking at this thing, you see a bunch of dots and then you need to make the correlation to what the dots represent. So with CO2, and I think this is maybe commonly known, you're basically shooting for less than a thousand. And if you can be in the under 600 range, that's considered to be good and you're not going to have any adverse effects. Outdoor levels range from four to 500, depending on where you are and what's going on in your region. Once you start to get in this elevated and well beyond the 1000 mark, that's where the research says you're going to start to feel some of the effects, less productivity, feel stuffy, things like that, adverse effects to comfort all that stuff.

With TVOCs, we're looking at parts per billion here. These are the ranges we want to be in. So again, try to keep it under a thousand. Once you get above that threshold, you might start feeling irritated stuff on your skin, have some breathing issues. You're breathing in kind of chemical off gas, so you can guess what. And then small particulate PM2.5, you really want to be under 15 here. And this is the one where, if the content gets above a certain level, you could end up with respiratory issues.

This is fun. So this is a snapshot of the Sense Edge Mini. So different from the platform I was just showing you. This sensor is in our bedroom. It's the place we spend the second most amount of our time sleeping.

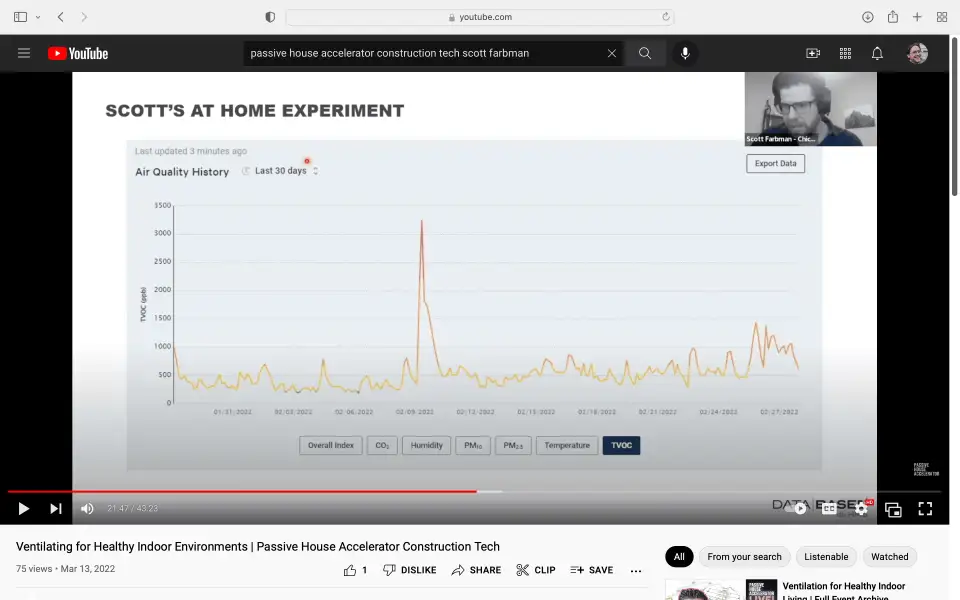

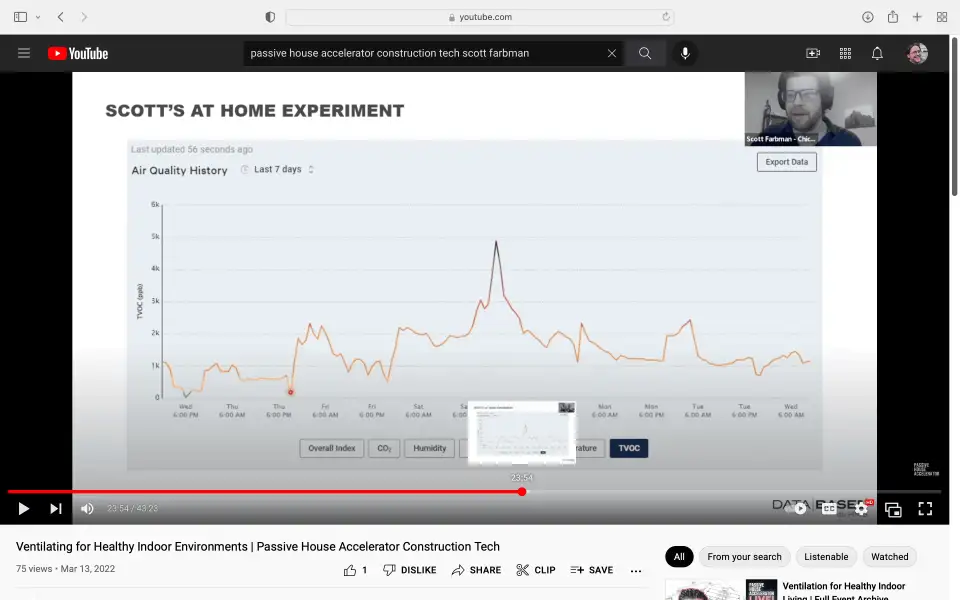

We have the Aware Element is in our kitchen living room area, the main place where we spend our time cooking and hanging out. But this is a TVOC reading across the last month, and I've noticed that we've had really elevated levels of VOCs in our bedroom. And for the life of me, I can't figure out why. And every night you can see a there's a dip and a dip, and there's a dip because we've been opening windows in our balcony door to get as much fresh air in before we go to bed. And then right after that, just shoots right back up. And I don't know what's going on. And this is a frustrating thing, and I think it kind of falls into the ignorance is bliss category a little bit. If you weren't tracking this, I would've never known this was a problem and I'd be living happily and not be stressed out over this.

But because I know it's an issue, I'm trying to desperately figure out what's going on. And one of the complications with TVOC is it's a conglomerate of volatile, organic compounds, a lot of them. I don't know how many, but there's a lot. So you don't know which specific VOC is triggering the sensor to go bonkers until you do a really high-end indoor air quality sampling and send it to a lab. So that's kind of where we're at. This crazy spike, I don't know what we're doing. We don't have crazy cosmetic products or anything like that going off. We don't have a lot of home cleaner. Really, This is stumping me. But what this is telling me is in our home, we don't have continuous fresh air being supplied to our bedroom, and that would really help us out here at big time.

This is just for reference. So this is the same thing, TVOC, but a different timescale. This is the past seven days. This is where you could see really see the dips. When we open the doors at night, before bed, it comes down, but then just, it goes right back up right away. So something weird is going on and we're going to figure it out eventually.

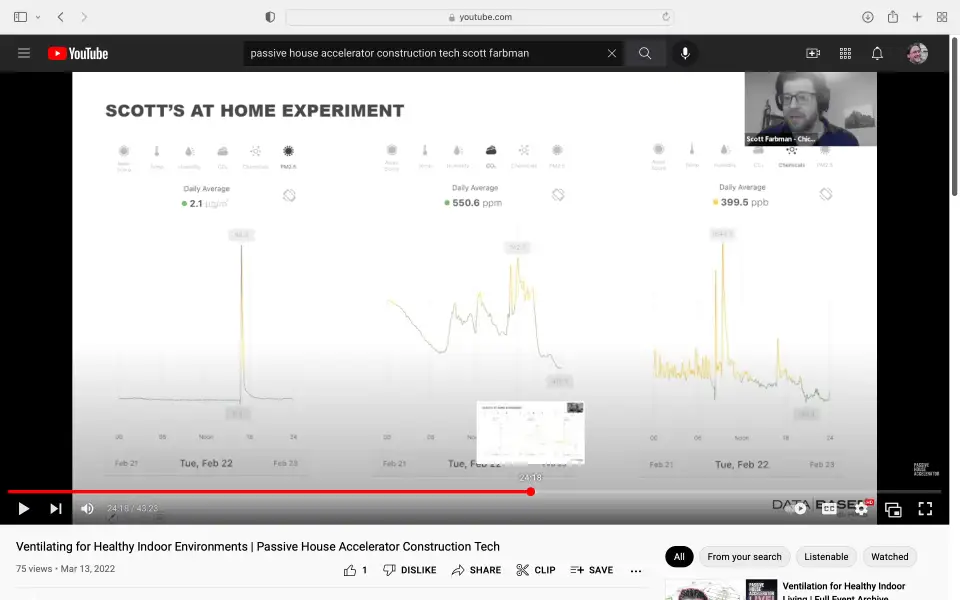

So this is the Aware Element. So you can get it off Amazon. I love the device, or I think we might have a sponsor link or something at some point. This is in our kitchen. So this is what I've been using to track the impact of cooking in our home, because I love to cook and I love to make a bunch of stuff and I want to know what's happening when I cook.

So on the left hand side here, this is PM2.5, and I was searing vegetables for dinner and it spiked to about 100, which is a very high level. And I have in a direct exhaust range hood, but it's one of those integrated microwave ones. So it aligns with the upper cabinets, and then the cooking surface still extends out a good foot, 18 inches from there. And what I found is that approach doesn't do a good job collecting the contaminants that burn off the front burners, and that has been a critical issue for me and I desperately want to change out that to a proper range if I can. That's my bandaid fix. My long=term fix is to switch to induction.

This is carbon dioxide. So still the same day, still the same cooking. And when you get two humans down there, you've got a couple dogs, and you've got open combustion kind of burning some of that free oxygen in your space, you start to see the parts per million of carbon dioxide take a bigger chunk out of what's there. So 740, 750, not critical, but it's starting to elevate and get to the point where I'm concerned. And again, this is a window open and exhaust going, and we're still up in this range, which is a little alarming to me. And then finally, same day but in the morning, looking at chemicals, so TVOC.

So my spouse, I love coffee, she bought me this really nifty siphon coffee maker, where, I don't know if you saw Breaking Bad, but it's similar to how they use chemistry to make coffee. It's vacuum activated and there's an open flame. And gosh, I'm not the greatest advocate because I do like to have some of these nifty things at home sometimes. So I'm a little bit of a hypocrite here. I'll be the first to accept that I like some of the still.

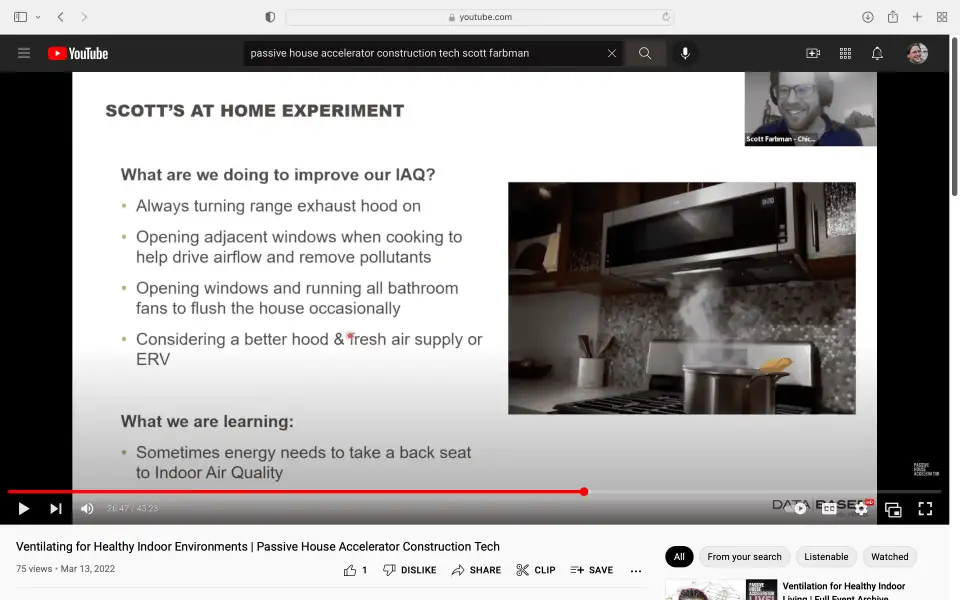

But open flame, I'm burning a alcohol based fuel, and the TVOC just boom, off the charts immediately. And again, exhaust on, windows open, doesn't matter. This is fun stuff. I hope everyone's having as much fun as I am because I love talking about this. So kind of the final wraps of my at home experience and experiment. So from what I've learned and seen, what I'm trying to do is, it doesn't matter what I'm cooking or what I'm doing in the kitchen. If the flame's on got to have the exhaust hood on, 100%. And you need to have openings nearby to allow that fresh air to come in and kind of flush the space and drive that airflow. We've also, because of the elevated VOCs that we've found, we're due kind of semi occasionally whole house flushes, where we open all the windows, turn on all the fans, and just try and get as much fresh air through the home as possible.

Then really, the pipe dream here is: How could I get an ERV into our house so that we're continuously ventilating at least our critical spaces where we're spending the most time? Our kitchen living and our bedroom. This is a good one for me, and I know this is a conflict in the Passive House world, but I'm learning that sometimes energy needs to take a backseat to indoor air quality. There might be people who disagree, but we're talking about two big risks here. A long term risk from energy use and climate change, and a short term risk to our immediate health. And I think sometimes we need to put our health forward, and there's good ways to do that within ERV so you're doing both. But I'm finding it's the dead of winter. I'm still going to open a window to try and ventilate things when I need to.

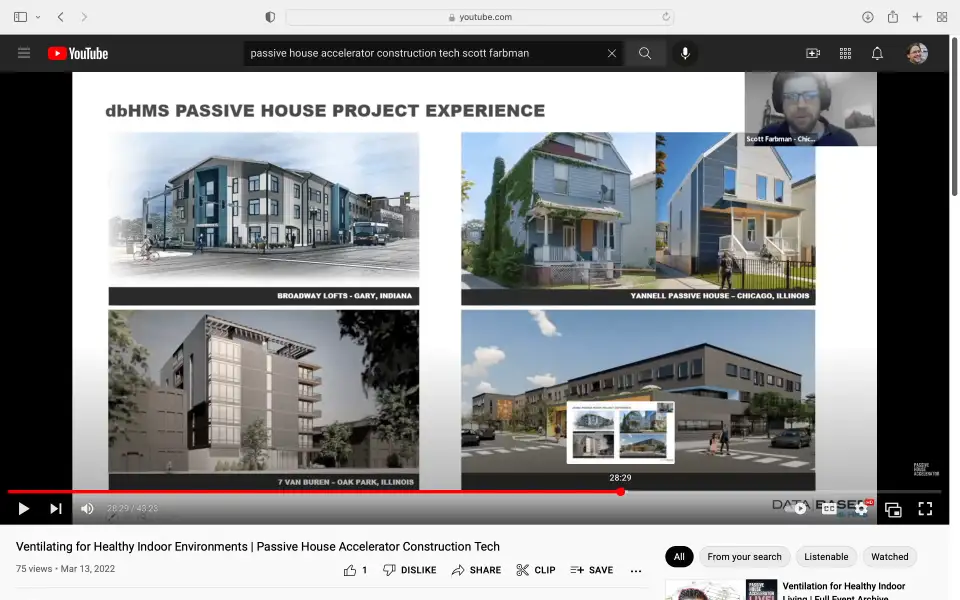

Second half of the presentation. So db HMS and Database Plus, our Passive House experience, runs the gambit a little bit right now. So my first and our first project was a single-family home retrofit and Chicago, very cool project. I think it's the one I presented on the last time I was here. It's hard to keep track of it all.

We've got a three-story, 50ish-unit multifamily project in Gary, Indiana, which is a little surprising. Gary, Indiana represent. Passive House. We've got a source zero. So a net zero energy Passive House project, just got through planning approval in Oak Park, Illinois. So that's just to the west of the city of Chicago. Sorry, I don't know what happened here. The tagged didn't come through, but this is another low rise Passive Hous multifamily project in the west side of Chicago that I think is in the 60ish-unit range. We got a couple other in feasibility study now. So we're looking at one high rise in Chicago. It was the recent winner of the C40 competition, if anyone's familiar with that. It was in the loop. So they're looking at: How could we make this high rise Passive House compliant?

And then I just kicked off a new project that I'm doing Passive House consulting on. That's going to be an 80-unit five-story multifamily in the west side of Chicago, mostly affordable housing, which is great. And this is affordable, 100% affordable. This one is 20% affordable and this one is 100% affordable housing. So love to see this stuff.

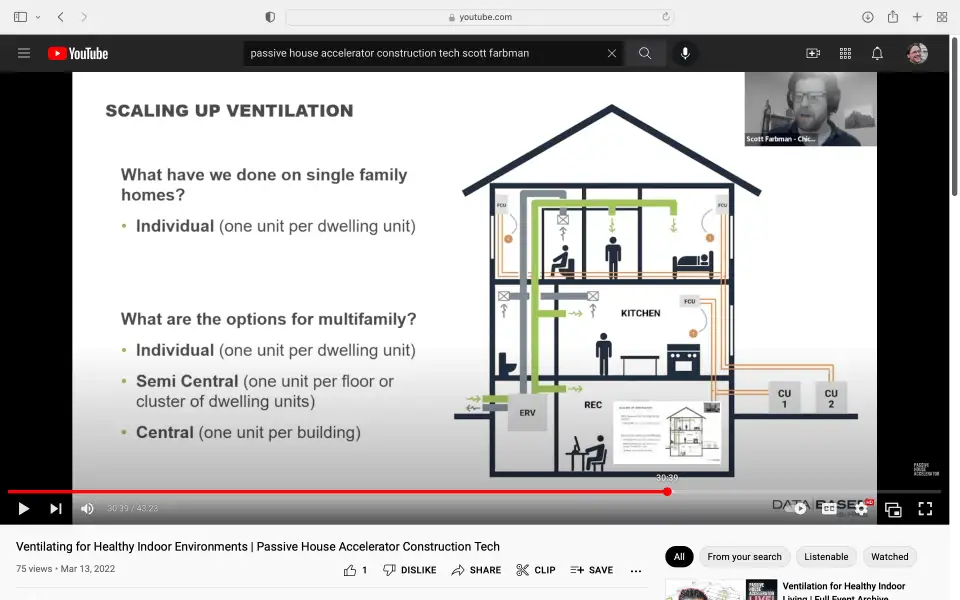

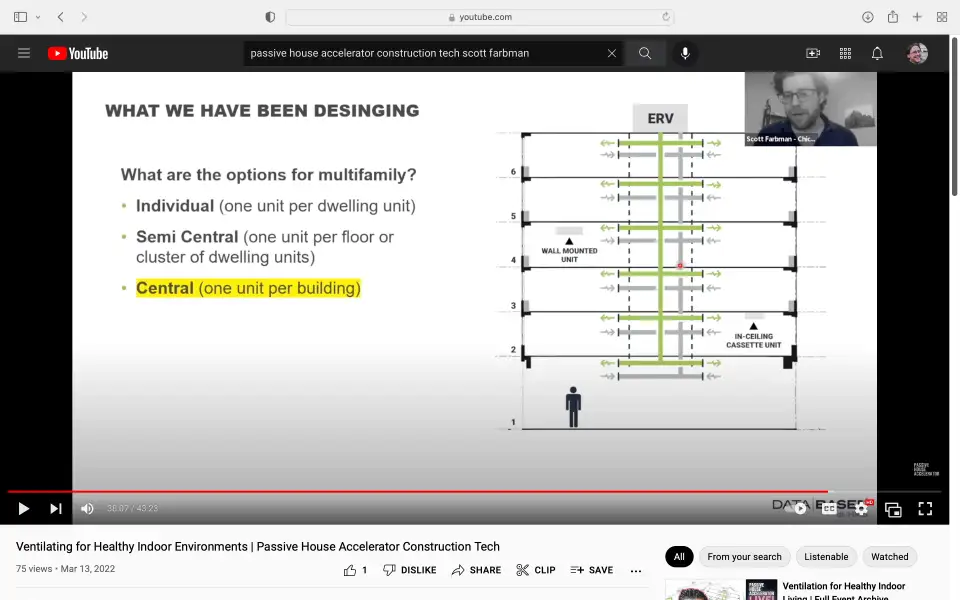

So scaling up ventilation. So what have we typically seen? I think the common practice, at least because I'm just guessing that most of us out there are used to seeing this on a single-family home platform. And that's an individual ventilation system. So you have one unit that is providing ventilation and exhaust to the entire house, or the entire blowing unit. Then what are our options for multifamily and how do you scale that up from what we're used to on a small house to a very large building? So we have three options. We have the individual, so it follows suit with the single-family home approach. You have one unit per dwelling unit that provides ventilation exhaust. We have the semi central approach, which it's looser, but it's basically one unit serving a number of dwelling units. So the final option here is central. One unit for the whole building. Could be split into two, maybe one serving one side, one serving the other side, but it's generally a centralized approach.

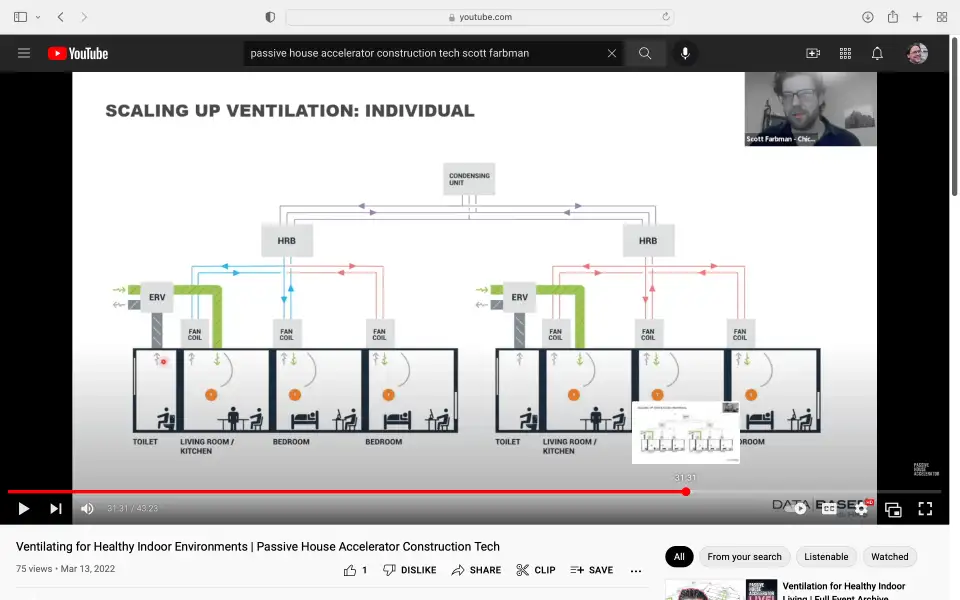

So what does this look like diagrammatically? This is our individual approach on a multifamily level. So you have an ERV per dwelling unit that is supplying to each, and it's exhausting from all the main areas, kitchen exhaust, toilet exhaust, all coming back to ERV, supply coming out. Little bit of a mishap here, just imagine this green line also coming through on all these rooms. So this is how individual would look.

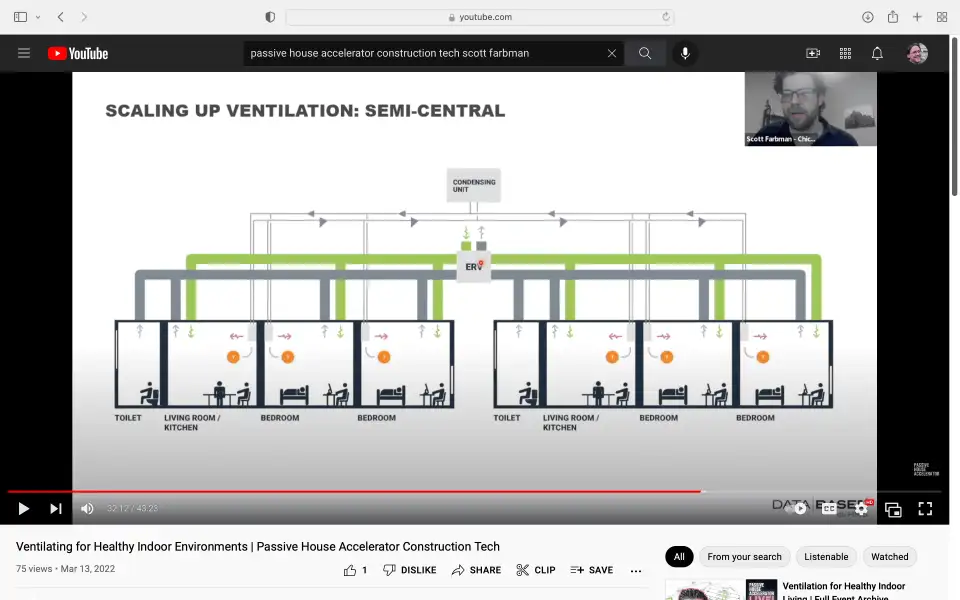

Now, let's go one further. This is semi central. So you would have a block of units that are served by one ventilator, piece of ventilation equipment here, preferably an HR ERV. And this is doing the same thing individual does, but it's serving multiple rooms. So you've got exhaust from different dwelling units coming back to one unit and you have supply going out to multiple apartments.

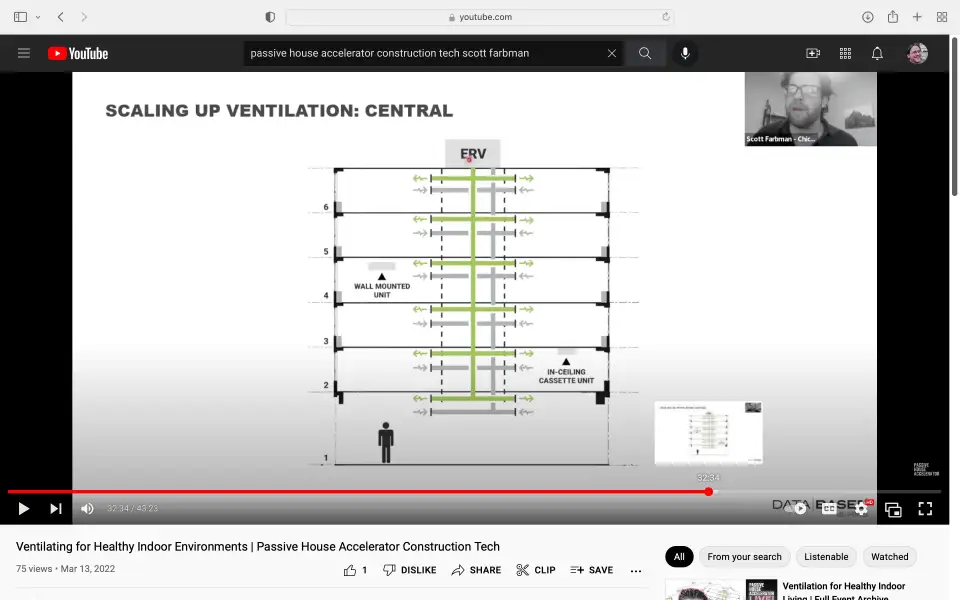

And here's our central approach. Diagrammatically, this is how we've shown it, but this isn't how we typically do it. So one unit probably on the roof and it branches down and it serves all of the units, both supply and exhaust coming back up, each unit, each floor, everything from one unit. Now I'll throw the caveat in here, what we found to work better, and I'll probably touch on this later, but I'll say it now is: From the centralized unit, we distribute horizontally on the top level. So we ask our nice architect friends to give us a little bit more floor height on the top level. So we'll spread out our ducts there and then we'll come down vertically in chases.

So you're doing most of your horizontal at the top, and then you're simply coming straight down vertically at different points on the floor plate. And we found that this approach is the easiest way to distribute, save on duct work, and limit your static pressure and fan power if you're going centralized.

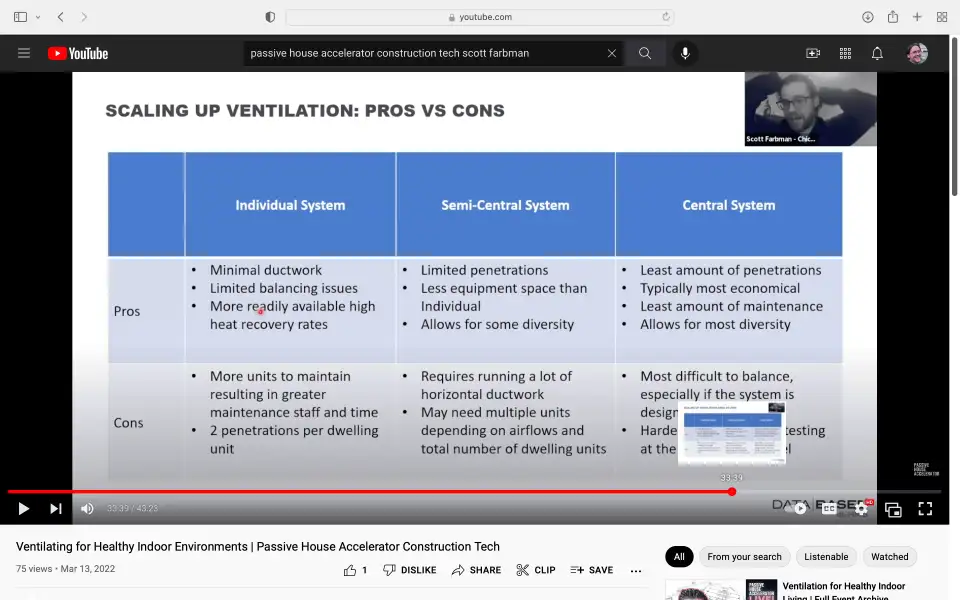

So let's talk about pros and cons of each quickly, and these are the pros and cons that I've seen. There's probably more out there, and if anyone else has some to add, let's get it in there later during the discussion. So individual systems, Minimal duct work, you're only supplying and exhausting very close to the unit. Don't need to run through corridors, anything like that, or common corridors. Limited balancing issues, because you're only supplying to those rooms directly at the system level. Probably a bedroom, common area, pretty limited. Another big pro that we're finding is higher recovery efficiency rates are more easily attainable at the smaller system level. So like the Zender unit has a really high efficiency rate, easier to get that than the centralized efficiency rate. And I'll talk about that in a second. The cons that we're hearing at least from the developers who own and operate their building, and I know Tim McDonald has said this too, the individual unit by unit results in a lot of filters to be changed by maintenance staff. You have to go and change as many dwelling unit departments, there are that many filters.

So there's a lot more at the equipment level to maintain because there's many more units and it's spread out across building. This is another one that is a pain point for some of the Passive House people out there, two penetrations per dwelling unit. So you need to exhaust and bring in fresh air at each unit. So every apartment is going to have two penetrations to handle fresh air and exhaust in and out of the building. A lot of architects don't like that aesthetically because you have a lot of grills and stuff in your facade. I know that there's some creative ways to do this. I've seen some people present it in a soffit on a balcony, but at the end of the day, you have a lot of holes in your building that you need to make sure are sealed properly.

Let's go to semi central. So less penetrations because you've just reduced the number of units, less physical space required for equipment because you don't have every unit in each unit. You've got a semi central, maybe let's just say one per floor. Maybe you could stash it in a ceiling somewhere, maybe you have a closet dedicated for it. Just less physical area required. And then it allows for some diversity. So we'll get into diversity a little bit later, but if you have boost modes on your fans in your bathroom to help manage some of the humidity that comes from the shower, so you might be cranking up from 20 CFM to 60 CFM. When you have multiple apartments on that unit, you could take some diversity there and say, "Well only 30% of the people are going to be boosting at once." So it gives you some flexibility on system sizing, but you're also taking a little bit of risk there because you could run into capacity issue.

Cons, running more duct work than individual. You're probably running a lot of horizontal duct work in the corridor. Corridors are already tight with fire protection and other things. It's just more to manage. And then you may need multiple units depending on airflow. So hopefully you have one per floor, but you might need two. You never know until you get in there and design.

Central systems, least amount of penetrations. We found it, so far, to be typically the most economical and that might surprise some folks out there. It's the least amount of hours of maintenance, because you're only changing one filter and you're only maintaining one unit and it allows for the most diversity. So you're taking diversity across every unit in the building. Cons, it is more difficult to balance, especially if you're doing diversity. So of course trade offs to everything. And then, we found it's been harder to verify in the field because at least PHIUS, Passive House US requires testing it at a unit level, but then you also have this thing operating at a system level. So it's been difficult to juggle those two things.

So what have we been designing on our multi-family buildings? We have been going predominantly towards the centralized system, and we've found that, at least in our Chicago buildings, we haven't been able to get the air flows low enough to design and size an affordable individual system. We really want to do an individual unit by unit, because I think it gives you the best performance, but we just haven't been able to get it. And then another our benefit to the centralized system is we can fine tune the total system size to the diversity, so we don't need a huge unit because we could take some savings on the diversity, assuming that only half the people are going to be boosting at once or whatever the metric is there.

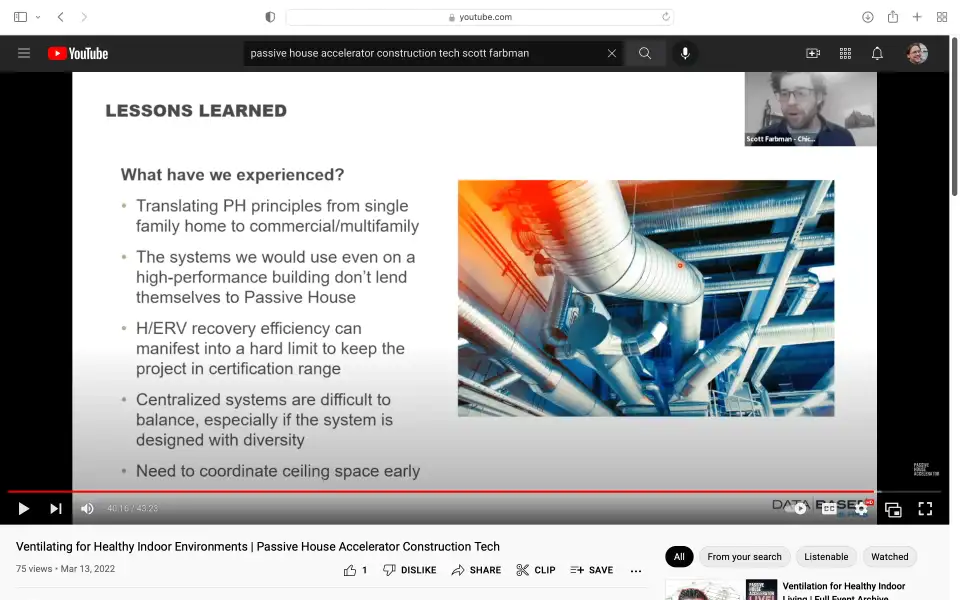

What are some lessons learned from our centralized approaches so far? We've found that translating Passive House principles from single family home to multifamily commercial is incredibly difficult and wildly challenging. We have also found that the systems that we would typically use, even on a high performance building, don't really lend themselves well to the Passive House requirements. And I think recovery efficiency rates is a key indicator there, and also your fan power too. Passive House has a really fine requirement, not a requirement, but due to the space heating load requirements, you have to be really careful with some of these things. And I'm going to get there in a second. So heat and energy recovery ventilator efficiencies can manifest into a hard limit to keep the project in certification range. So we found that 80% efficiency at our dedicated outdoor air system will not get us to the heating load requirement through Passive House. And we need to up it to 85%.

And what I'm trying to say is, typical off the shelf unit could tank your certification. So you need to be very mindful of the heat recovery, both sensible and latent, on the outdoor air equipment, and make sure that you're working in an integrated and collaborative effort with whoever's doing your WUFI model or your PHPP model. As I noted before, centralized systems are a little difficult to balance, and if you are doing ducting in your corridors, you need to coordinate that ceiling space as early as possible.

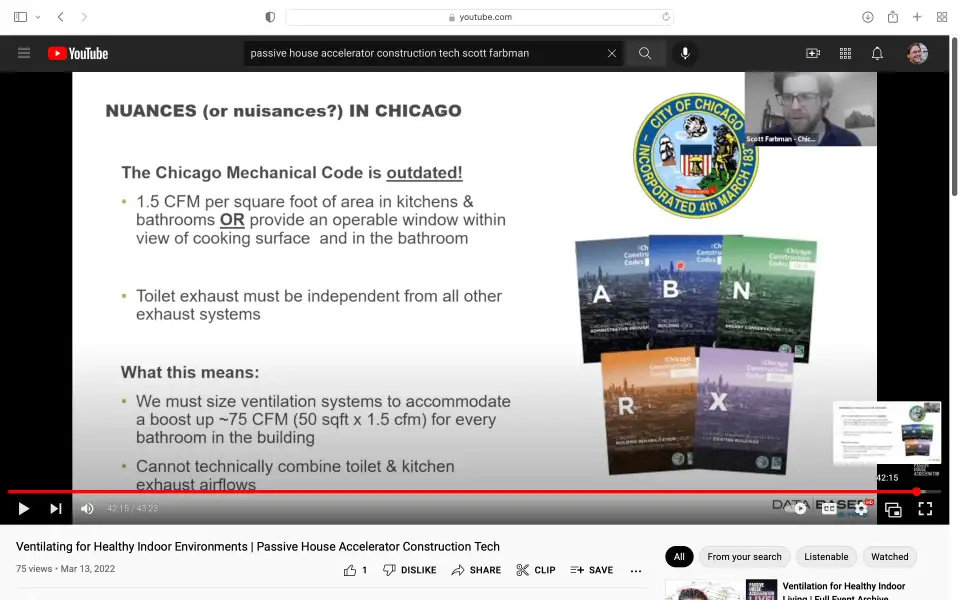

Last slide here, I'm going to leave you with some nuisances or nuances of Chicago, which I like to talk about a lot. I'm very passionate about this, and I do my best to advocate for improving code and policy, not only in Chicago, but wherever I can be part of.

So the Chicago mechanical code is severely outdated, 20 years, at least, behind the times. So what the code requires is 1.5 CFM of exhaust in your bathroom and kitchens or an operable window. So what that means is in a bathroom, especially in a multi-family design, which doesn't typically get a window, we have to design for about 75 CFM of exhaust airflow in that bathroom. And we know IMC, ASHRAE and Passive House says we want something like 20 continuous. City of Chicago doesn't recognize 20 continuous. They say, "Doesn't matter. We need it to be 1.5 or you put a window in there. No, if ands or buts." Same goes for the kitchen. Kitchen is a little bit more of an easy hurdle because you can have a window somewhere in the general vicinity of kitchen on a multi-family project.

So we've actually found that to be better for us because we don't need to meet any other wacky requirements. We just use the window for code compliance, and then we do whatever mechanical ventilation exhaust. Another really terrible wacky thing. Toilet exhaust has to be independent from all other exhaust flows. So we can't co-mingle toilet and exhaust back to our energy recovery unit to recover all that heat. We have to only do toilet or only do kitchen. We can't combine. There's no way around it. Maybe we go for a variance. So hopefully that shed some light on Chicago being a thorn in my side when it comes to Passive House design. And with that, I end the presentation. I probably went too long. I got really excited about the front end. Really wanted to talk about indoor equality. Yeah. Thank you so much for having me, excited for questions and discussion.