[Editor’s Note: This article was originally published as part of the 2019 NAPHN Policy Resource Guide, release at its 2019 conference. Registration for this year’s NAPHN conference, PASSIVE HOUSE 2020, opens March 2.]

One of the more exciting Passive House policy breakthroughs to emerge in the United States over the past few years comes from an obscure source: a tweak to the point-scoring system used to rank applications for Low Income Housing Tax Credits in Pennsylvania. This little policy tweak has sparked a big boom in Passive House development in Pennsylvania that is notable in several ways.

First, the policy requires zero outlay of government capital.

Second, developer participation is entirely voluntary, yet very high.

Third, the same policy tweak could be replicated in all other 49 states to spur a massive uptick in Passive House development nationwide.

Fourth, the policy ensures that the health and energy-saving benefits of Passive House buildings are shared with low-income people.

THE PHFA MODEL

Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTCs) are a key mechanism for funding affordable housing across the U.S. These federal tax credits are administered by each state’s housing credit agency based on a set of decision-making criteria called the QAP (Qualified Allocation Process) that reflects a given state’s priorities for the type of affordable housing it wants to support (location, income-level served, community development goals met, etc.). Every year, affordable housing developers submit project proposals for LIHTC funding that are then scored based on each state’s respective QAP. In competitive programs, only the highest scoring applications receive LIHTCs.

In 2015, after advocacy by Passive House leaders like Tim McDonald (Onion Flats) and Laura Nettleton (Thoughtful Balance), the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency (PHFA) made the Passive House-related tweak to its QAP for LIHTCs. It began awarding 10 QAP points (out of 130 total) to LIHTC proposals that incorporated Passive House in project design and construction. Whether to incorporate Passive House is entirely voluntary, but afford- able housing developers in Pennsylvania know that if they can do so in an affordable way that “pencils” for their project that they will have significant competitive advantage in securing LIHTCs for that project.

In a highly competitive environment—just one in four LIHTC proposals to PHFA is successful—the Passive House QAP points are having a big impact. During the first three years of the Passive House policy, 28% of LIHTC proposals were for Passive House projects. Twenty-six Passive House projects were awarded LITHCs during that time, meaning that nearly 900 units of Passive House affordable housing have been built or are underway in Pennsylvania today.

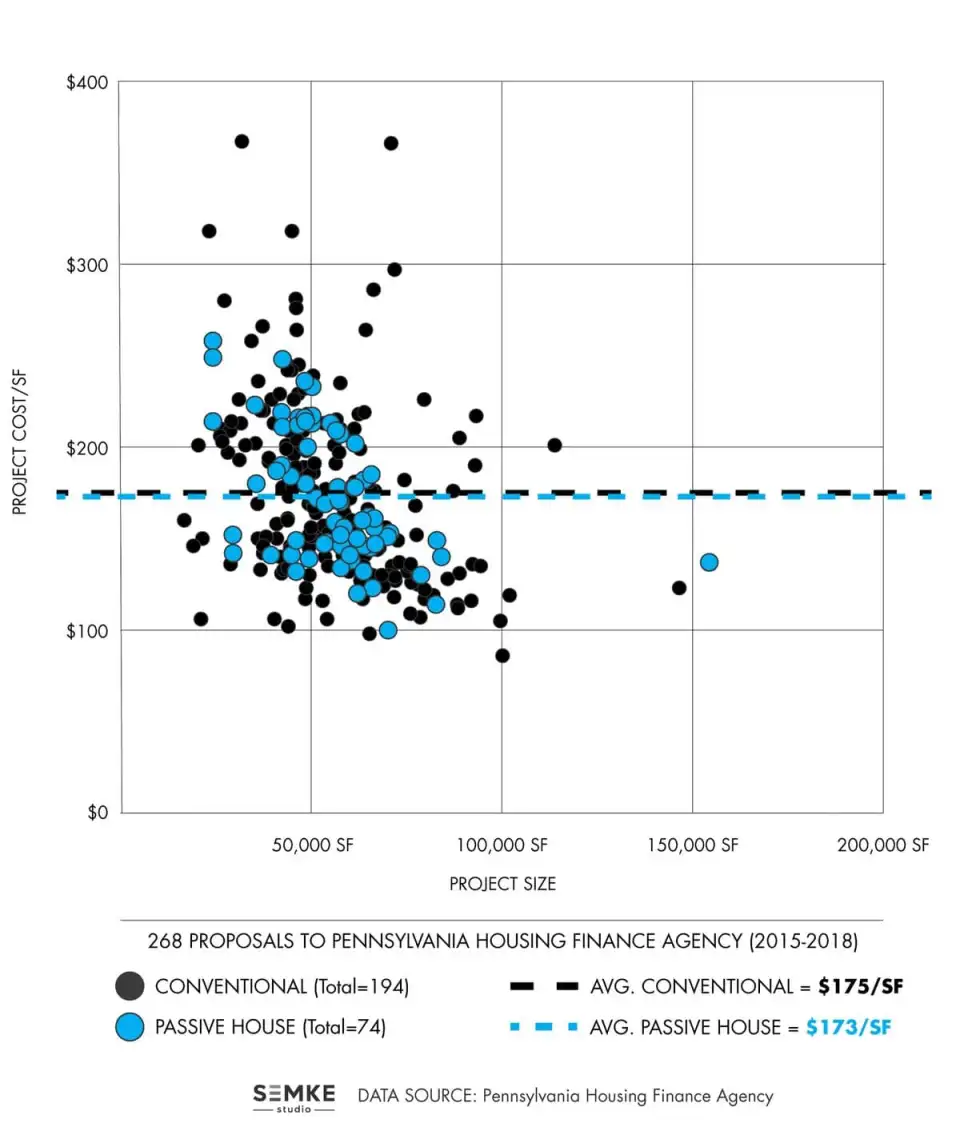

Notably, the Passive House projects don’t seem to be more expensive to build than conventional buildings, likely thanks to the early integrated design process that development teams are compelled to engage in so that their LIHTC proposals can be competitive. According to PHFA data, the construction cost premium for Passive House versus conventional projects was 5.8% in the first year, 1.6% in the second, and minus 3.3% in the third year, suggesting that learning and innovation by project teams may be driving down costs over time.

THREE KEY INGREDIENTS

The remarkable success of the PHFA model, as well as tireless outreach work by Tim McDonald to share the Pennsylvania story with other states, has meant that several other states’ housing credit agencies have included Passive House in their QAPs. But so far we haven’t seen the same sort of breakout success as experienced at PHFA. Why? Through my attempt to replicate the PHFA model in Washington State, I’ve discovered three key ingredients that I believe must be in place for the policy to succeed.

The LIHTC process must be competitive. Just one in four LIHTC proposals to PHFA are successful, making any competitive advantage highly valuable to project teams.

In Washington State we have succeeded in persuading the Washington State Housing Finance Commission (WSHFC) to award Passive House QAP points as part of its 4% LIHTC program. However, all proposals that meet a minimum threshold are awarded 4% LIHTCs in Washington. Passive House therefore provides no advantage so those QAP points are unlikely to be sought by project teams. Washington’s 9% LIHTC process is competitive however, so WSHFC could make an impact by adding Passive House QAP points there.Passive House points must be significant. PHFA awards Passive House projects 10 points out of 130, weighting Passive House at nearly 8% of the total possible points.

Other states’ housing credit agencies that do include Passive House QAP points typically weight Passive House significantly less. Vermont Housing Finance Agency (VHFA), for example, weights Passive House projects at half the level that PHFA does. By increasing the points awarded to Passive House projects, housing credit agencies like VHFA would provide more competitive advantage to Passive House and likely see more uptake by developers.Passive House must not be lumped together with “easier” green certifications. The only way to earn the full 10 QAP points at PHFA is to do a Passive House project.

Other states often lump Passive House with less stringent (and more familiar) green certification programs, all but ensuring that Passive House is not adopted by developers. Idaho Housing and Finance Association, for example, allocates equal points in its QAP to developers’ choice of LEED for Homes, NW Energy Star, Enterprise Green Communities, Indoor Air Plus, or Passive House (PHIUS or PHI). Achieve any one of these certifications and your project maxes out the “green building” points available in Idaho’s LIHTC process, leaving no incentive for developers to try something new and ambitious like Passive House.

THE NEXT STEP

States like Washington, Vermont, Idaho, and others who have incorporated Passive House into their respective QAPs should be commended for taking an important step in the right direction. But in order to fully leverage LIHTCs to create a PHFA-like Passive House boom that benefits thousands of low-income residents, these states should take the next step and incorporate all three key ingredients that make PHFA’s policy successful: start with a competitive process, give Passive House proper weight, and don’t undermine Passive House with an easy out.

[Featured image above is of McKeesport Downtown Housing, a PHFA-funded Passive House retrofit designed by Thoughtful Balance. Image courtesy of Zola Windows.]