Mercy Greenbrae Apartments at Marylhurst Commons did not begin as a Passive House project. A partnership between the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary and Mercy Housing Northwest, the 100-unit and 100% affordable apartment building in Lake Oswego, Oregon, was always intended to be high-performance, but the decision to pursue Phius certification occurred only after design development had started. The unorthodox move may have caused some sleepless nights for the team, but it did not prevent them from passing their final blower door test.

Repurposing the Commons in Lake Oswego

As rigorous as Passive House standards are when compared to code minimums and as much as the pursuit of certification may seem daunting to those who are not experienced with passive principles and methodologies, the success of this project should be an inspiration. It highlights that a team with a strong foundation in high-performance building and willing partners can overcome the challenges associated with changing course midstream. Once it receives its final certification, Mercy Greenbrae will be one of the largest Passive House projects on the West Coast.

The Sisters and Marylhurst

Mercy Greenbrae is located on the former site of Marylhurst University. A steady decline in enrollment that started in the late 2000s led the university to close in 2018, and ownership of the 4.3-acre campus reverted back to the school’s original founders, the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, who have owned that property and the surrounding area since 1906 (see “The Evolution of St. Mary’s and Mary’s Woods”). In total, the religious organization’s holdings in their corner of Lake Oswego amount to 63 acres.

The property surrounding the university did not remain undeveloped over those years. The Sisters have created a thriving community that encapsulates their mission of education, social justice, and the empowerment of disenfranchised people. They have built educational residences and offices for members of the religious organization, as well as an expansive retirement community (Mary’s Woods), several schools, and a Franciscan prayer center. Creating deeply affordable housing seemed like a natural progression on the former site of two of the university’s student residences and a common building, given the Sisters’ commitment to serving marginalized communities and the Portland metropolitan area’s dire need for more affordable housing. As the three buildings were beyond repair and could not be salvaged, the Sisters decided to demolish them and erect a new one in their place.

For help with the development, the Sisters turned to Mercy Housing, with whom they entered into a ground lease in 2022. Originally founded by six communities of Catholic sisters in the early 1980s, Mercy currently develops, manages, and owns affordable housing complexes across 41 states. Mercy Housing Management Group, its property management division, is responsible for over 300 properties and more than 22,000 units. Its northwest division, Mercy Housing Northwest, owns and operates 52 properties across Idaho, Washington, and Oregon.

Despite its footprint in the region, Mercy was not familiar with the affordable housing landscape in Portland and did not have a project architect in mind as they began to build their team. For assistance, they reached out to Walsh Construction Co. According to Walsh Project Manager Brian Ames, Walsh and Mercy have worked on at least a dozen affordable projects together, the majority in the Seattle/Tacoma region, and have a strong and established relationship.

Walsh directed them to Carleton Hart Architecture (CHA), a certified B Corporation and Just label firm based in Portland with a similar commitment to social justice as the Sisters and Mercy. Walsh told Mercy that they had worked together on multiple successful projects with CHA, and that CHA had a long history of building high-performance affordable housing in Oregon that was not only architecturally interesting but informed by CHA’s belief that affordable housing has the power to improve communities.

It turned out to be a very good fit; CHA was promptly hired to design the building.

Rethinking What Affordable Can Mean

“We were part of a young industry that was trying to change the way we think about affordable housing,” Carleton Hart Architecture Principal Brian Carleton says of the firm’s early years. Even before the Great Recession, CHA recognized that affordable multifamily housing could be sustainable, efficient, innovative, and even beautiful, defying the prevailing wisdom at the time, which was that the typology needed to be utilitarian.

“These projects are important parts of our community,” Carleton says. “They really add to and diversify neighborhoods, so it’s important that they’re built right.”

The city government and the people of Lake Oswego agreed with this assessment, as well as CHA’s design, and approved the project at the end of 2020. While CHA’s philosophy helped to warm the suburban community to the promise of affordable housing, Carleton personally credits CHA Project Manager Melissa Soots, who presented the team’s vision during design review, for the success. “They came to an understanding that they really do need more affordable housing in the city—and, with the right team, that it can be done well,” Carleton says.

Carleton acknowledges that even with supportive communities and development teams, there have been limitations to what can be built. “I think our effort in sustainability and innovation always comes with a healthy dose of concern for what’s feasible—what we can really do with the dollars at hand,” he says. Consequently, they had regularly been able to pursue certification through Earth Advantage (an independent, third-party verifier of green buildings based in Oregon), but had yet to attempt Passive House certification.

However, the question of doing a passive project had long seemed less like an “if” and more like a “when” for the firm, as several individuals at CHA are certified Passive House professionals. It was no surprise that the topic came up repeatedly during pre-design with Mercy Greenbrae. Even when Walsh officially signed on during the concept design phase in May 2020, it continued to seem like a possibility.

“We are always asking how we can push our sustainability goals beyond code in a way that promotes health and wellness,” Mercy Housing Northwest Vice President of Real Estate Development Colin Morgan-Cross explains. “At the end of the day, families deserve a comfortable, safe, and healthy place to raise their children.”

Morgan-Cross adds that the improved indoor air quality, thermal comfort, and noise control in Passive House buildings have been some of the primary motivators in Mercy’s interest in the standard. Optimizing performance and providing tenants with a healthy and comfortable home shouldn’t be an either/or decision, Morgan-Cross observes, though the upfront costs to do so can push budgets beyond their limits.

“We knew that Mercy Housing had strong sustainability goals and Walsh has experience with Phius,” Soots adds. “The Sisters of the Holy Names really wanted to push sustainability, as well.”

Unfortunately, as the project progressed, it seemed more and more like Phius certification was simply beyond budget limitations. Once the team entered into design development, CHA and Walsh assumed that the matter was settled.

Rethinking Passive House

According to Morgan-Cross, the Sisters have always seen themselves as the long-term stewards of the land, and they take both resiliency and durability very seriously. “They’re thinking about what this property will be like in 200 years,” he says.

As a result, they decided to make a significant philanthropic contribution to the project that largely covered the upfront costs of Phius certification. Additional funding sources came from Oregon Housing and Community Services, Metro, and the Clackamas County Housing Authority.

The decision occurred about a month into design development. The design team was excited, of course, but they also knew that this would require rethinking many of the building’s details.

The good news was that there were several factors working in their favor. First and foremost was Walsh’s experience with the nuances of Passive House construction and the process of certification. “I think the greatest benefit that Walsh brought to the table was just the confidence of having done it before,” Carleton says. “It is really, really helpful to have at least one member of the team who has gone through it,” he emphasizes.

This confidence translated into clear performance and cost comparisons that helped CHA determine if certain aspects of its original designs could remain in place or if they needed modification. Walsh Quality Director Sharon Libby Eyerly notes that CHA has a “collaborative spirit”, and that their willingness to work together made the process a lot easier.

Eyerly and her department are experts in collaboration and sharing information, and they have been instrumental in making sure that the lessons learned by Walsh as a company are shared out to their field crews. “Since our quality department and our quality managers touch every project, we have a really great way of disseminating that information and recycling what we learned back into the next project,” she says.

Beyond their collaborative spirit, CHA had already adopted many passive building techniques as part of their standard practice even before they began working on Mercy Greenbrae. As one example, they have long relied on building orientation to optimize solar gains in the winter and use existing trees and passive shading elements to limit these gains in the summer. Another example clearly illustrated by Mercy Greenbrae’s massing is the firm’s use of simplified form factors. The four-story, U-shaped building is accented by a pair of setbacks on the fourth floor, which are each only about 2,500 square feet. The design decision may have been unintentional from the perspective of achieving Passive House performance when it occurred during schematic design, but it turned out to be serendipitous once the team decided to pursue Phius certification. According to Soots, Walsh’s coaching was most helpful for the team as they figured out how to detail the enhanced air sealing techniques necessary for Passive House, resulting in some unique assemblies.

Following the decision to pursue Phius certification, an early decision that had to be rethought was which windows and doors to specify. The team needed a manufacturer that could supply Phius-certified components and do so within a relatively short lead time. Innotech Windows + Doors was able to meet the demanding timeline with certified components, and ultimately supplied the fenestration systems for the project. As Innotech’s double- and triple-pane windows are both engineered to achieve exceptional levels of airtightness, the team was able to attain Passive House levels of performance with the double-pane Defender 76TS and without the added cost of the triple-paned model (see “Is Triple-Pane Always Necessary?”).

Collaborating on Campus

The construction of Mercy Greenbrae began in September 2022, two years after Lake Oswego approved the rezoning. While the design may have been simplified, the project was still quite the undertaking because of its size. Mercy Greenbrae contains over 100,000 square feet of conditioned space and 100 large units. As the building is intended to primarily accommodate families, only 17 of the apartments are one-bedroom. There are 205 bedrooms across the 100 units, and Mercy provides on-site education programs and other supportive services that focus on helping families and children thrive while building community in the building.

The building sits on a six-inch stem wall foundation with a two-foot continuous footing. A three-inch layer of rigid XPS insulation is located vertically on the interior side of the foundation wall and extends four feet horizontally under the slab. Additionally, a 2x8 exterior layer of XPS is located at the slab elevation to provide continuous insulation and address potential condensation concerns where the interior-side insulation is interrupted by interior footings.

The wall assembly did not require exterior insulation layers on account of the region’s temperate climate, according to Eyerly. Instead, the 2x6 wood-framed wall contains fiberglass blown in the cavity and a sheathing layer made of plywood. The plywood seams are sealed with SIGA Wilguv tape. Tyvek commercial wrap provides a water-resistant barrier and secondary air barrier.

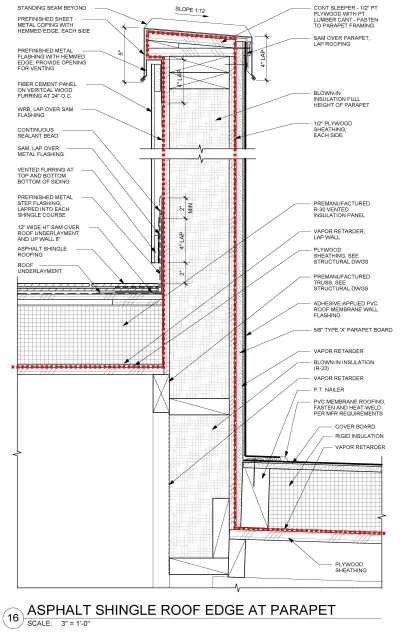

As several members of the team from both Walsh and CHA explain, the roof was one of the trickier assemblies. Eyerly describes it as having a flat gully or central walkway area where some mechanicals and a PV array are located. The gully is surrounded by a sloped roof. While complicated, the initial design was shaped by regulatory issues concerning height and the belief that a sloped roof fits the context of the site better than a flat roof with parapet walls.

The design became significantly more complicated following the decision to pursue Phius certification, but the team managed to weave the continuous air barrier through the various assemblies, as shown in the details (see Figures). According to Nate Latigue, a job captain for CHA, the assembly of the sloped portion of the roof contains an air and vapor barrier sandwiched between the roof deck and a Hunter panel system, which provides rigid roof insulation. Specifically, the Hunter Panels product used is the Cool-Vent, which is a vented nailbase product that provides ventilation under the secondary layer of plywood and asphalt shingle roofing. The portion of the roof that is flat consists of plywood, the air and vapor barrier, polyisocyanurate rigid insulation, cover board, and then thermoplastic polyolefin (TPO) on top of that.

Throughout construction, air sealing continued to be one of the more intimidating and nerve-racking aspects of shooting for Passive House certification. However, the team from CHA felt that Walsh’s confidence both during design and on the jobsite helped to calm their anxieties. As Carleton says, “It’s wonderful having your site superintendent just say, ‘If we do it this way, we’re going to pass those tests. Do not worry about it.’”

Another element of the building that proved daunting was the installation of the all-electric domestic hot water system. Even before deciding to strive for Phius certification, one of the initial sustainability requirements for the Sisters and Mercy was that the building be all-electric, and the team accepted the challenge. As a result, Mercy Greenbrae is one of the first multifamily buildings in North America to be equipped with Mitsubishi’s domestic hot water heat pump system.

Meanwhile, heating, cooling, humidity control, and ventilation for the building are provided by a centralized dedicated outdoor air system (DOAS). The normal settings for the system will be able to keep occupants comfortable for the vast majority of the year, especially given the mild climate of the Portland area and the building’s well-insulated envelope. For excessively hot days, the team worked with ColeBreit Engineering, the mechanical and plumbing engineers on the project, to devise a way to add more cooling capacity to the HVAC system. The energy recovery units have heat pump coils that utilize refrigerant to cool (and heat) the air further to provide ventilation air at a tempered, comfortable temperature to the apartment units and common areas.

Maintaining a steady temperature in the shared laundry room is also a concern, as it sits within the Passive House envelope. To prevent overheating in summer or overcooling in winter, the makeup air louver actuator has been designed to respond to dryer operation. Soots notes that the space is cozy and that the best place for the actuator turned out to be nestled beneath the window. Rather than sacrifice this space to the mechanical system, the team instead created a small window seat in this space with a vent beneath it. As a result, residents can enjoy the view of the former Marylhurst campus as they wait for their laundry.

Rethinking What Community Can Mean

Construction on Mercy Greenbrae was completed in spring of 2024 and the building is now partially occupied—Morgan-Cross says that 93 families have moved in as of early October. As noted earlier, the project passed its final blower door test with a score of 0.049 cfm/sf @75Pa (0.041 cfm/sf @50Pa), recently received design certification, and can most certainly be deemed a success by any standard.

It’s also a success for Lake Oswego.

The city is not known for building a lot of affordable housing. Like many suburban communities, it has long eschewed multifamily housing of all types, including affordable housing. However, this is changing, and positive experiences with the teams like the one behind Mercy Greenbrae will only accelerate the push to build more affordable—and passive—housing in the Pacific Northwest.

“With the right partners, it is possible to do both,” says Morgan-Cross.

Project Team

Developers: The Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary and Mercy Housing Northwest

Architect: Carleton Hart Architecture

General Contractor: Walsh Construction Co.

Mechanical and Plumbing Engineers: ColeBreit Engineering

Electrical Engineers: PAE Engineers

Passive House Verifier: RDH Building Science

Passive House Consultant: O’Brien360

Windows Manufacturer: Innotech Windows + Doors

Passive House Metrics*

|

Heating demand |

4.63 kBtu/ft2/yr |

|

Cooling demand |

0.16 kBtu/ft2/yr |

|

Total Source Energy |

3,251 kWh/person/yr |

|

Air tightness |

0.041 CFM50 |

*Modeled.

The Evolution of St. Mary’s and Mary’s Woods

St. Mary’s Academy was founded in 1859 by the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, a Catholic teaching institution with roots in Quebec. The academy continues to operate in downtown Portland and is Oregon’s oldest continuously operating secondary school.

In 1893, St. Mary’s received a charter allowing them to offer baccalaureate degrees, leading to the creation of St. Mary’s College. Originally part of St. Mary’s Academy’s campus in Portland (where the combined institute was aptly known as St. Mary’s Academy and College), it was the first liberal arts college for women in the Pacific Northwest.

In 1906, the Sisters purchased a 63-acre property along the banks of the Willamette River in the southeast corner of Lake Oswego. The property, as well as the surrounding area, was largely undeveloped at the time, making it the perfect site for a suburban college campus. In 1930, the college separated from the academy, moved from Portland to the Lake Oswego campus, and changed its name from St. Mary’s to Marylhurst, meaning “Mary’s woods.”

Marylhurst College was originally staffed entirely by the religious organization, but the addition of new and more specialized academic programs led to the employment of faculty members who were not affiliated with the Sisters. The school continued to expand and ultimately became an independent corporation in 1959. It would go on to become a university in 1998.

Despite its growth in terms of offerings, the school remained quite small. The entire campus only took up 4.3 acres of the 63-acre property even after becoming a university.

Is Triple-Pane Always Necessary?

If you are certifying a project with Phius, the answer is ambiguous.

As controversial as this position may be, triple-pane windows can be superfluous on certain Phius projects in temperate climates where the enhanced U-values offer diminishing returns with respect to performance when other factors are taken into consideration. In the case of U-values, “lower is slower,” meaning that a lower U-value for a window system will mean that it is better at preventing energy transfer. However, preventing energy transfer is not the same thing as preventing air leakage, which can be a tremendous concern when the project goal is to meet Passive House’s rigorous standards of airtightness.

In the case of this project, the double-pane tilt + turn and fixed models of the Innotech Defender 76TS, which are Phius-verified components, were able to rise to the occasion. This is not the case with all double-pane windows, which can vary widely in performance metrics depending on manufacturer and model. As Jessica Owen of Innotech explains, “Not all windows are equal.”

Other factors to consider besides U-values include the embodied carbon involved in manufacturing and transporting triple-pane windows systems as compared to double-pane windows systems. (See Dyann Stewart’s article, “Upfront Carbon Emissions and the Built Environment,” which discusses the upfront carbon costs that arise from shipping fenestration systems internationally.) Cost is yet another factor. There is no doubt that triple-pane windows offer improved performance metrics compared to double-pane, but that boost in performance is not free.