Passive House Accelerator hosted its most recent Reimagine Buildings Conference, Designing for Fire Resilience, March 14. The conference was created and designed to offer clear and practical advice about fire resilience to architects, engineers, builders, and even homeowners. While wildfire resilience has long been a critical consideration for homeowners within the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) and exurban communities, wildfires have become a growing problem for those living in suburban and even urban areas. To avert future tragedies, we have to design communities and homes that can withstand wildfire events, and the numerous presenters and speakers at the conference provided strategies for improving fire-resilience and fire-hardening techniques based on real-world evidence. These are practices that owners, builders, designers, and architects can easily incorporate into their standard building practices.

Resiliency Takes Center Stage at Reimagine Buildings

For those who didn’t catch the three-hour conference, you can go back and watch the entire event by becoming a member of the Reimagine Buildings Collective. In addition to becoming a part of the RB Collective community, members get free access to future events, the opportunity to take courses on PHPP and WUFI modeling, and plenty more.

The Reimagine Buildings Collective brings together building professionals stepping up to tackle climate change.

While the entire event contains loads of insights, we thought it'd be worthwhile to highlight some of the points that came up during the final panel discussion, which was led by Andrew Michler. Michler is the Principal of Hyperlocal Workshop, a Passive House design group based in Colorado; organizer of Passive House Rocky Mountains; and author of “Hyperlocalization of Architecture,” a book on contemporary sustainable architectural archetypes.

Michler was joined by five panelists:

Bronwyn Barry, Principal of Passive House BB

Michael Ingui, President of Ingui Architecture; founder of Passive House Accelerator and Source 2050

Graham Irwin, Principal of Essential Habitat Architecture

Christian Kienapfel, Principal of PARAVANT Architects

Rob Nicely, President of Carmel Building & Design

Of the five panelists, only Ingui is not based in California. His firm is based in New York City.

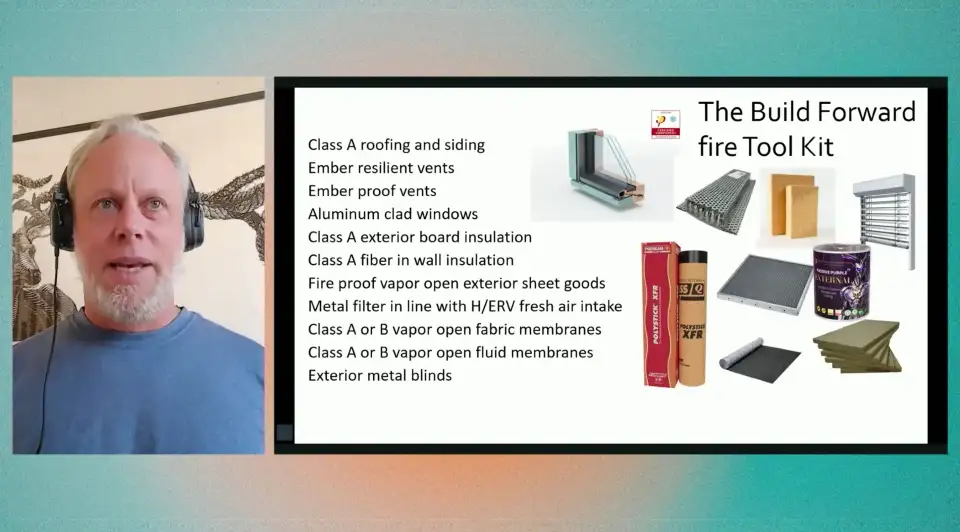

As is the case with Passive House design in general, the designing and constructing a strong building enclosure plays an enormous role when considering how to make a resilient home to wildfire. Some of the specific components were highlighted early on by Michler in a slide (see below).

However, one item on the list deserves special attention because there is a bit more nuance than meets the eye: aluminum-clad windows.

Detailing around windows can be crucial during a fire. If the framing can ignite, then the window unit can become detached from the building envelope and create an opening for fire. Using aluminum cladding can prevent that from happening because it is more fire-resilient than many other types of cladding.

One would be correct in assuming that aluminum windows offer comparable fire protection to windows that are aluminum clad, but performance then becomes an issue, as aluminum-clad windows offer better thermal performance. Similarly, aluminum typically contains more embodied carbon than natural materials, like wood, and those who are concerned with embodied carbon should try to minimize the use of aluminum in window systems.

As Michler notes, this is possible. Clever design can allow for a combination of aluminum and wood and refers to the window company SmartWin as an example. The firm uses wood for their interior framing, but the detailing on the exterior protects the frame by extending the insulation layer and then overlaying the frame with minimal external aluminum cladding. This technique can be replicated by designers. Barry, who operates out of the Bay Area, notes that this is becoming a relatively standard detail for her.

Another issue concerning windows and fire resilience is glazing. Irwin, who is also based in the Bay Area, explains that many conventional double-pane units may provide adequate performance the vast majority of the time, especially in temperate climates, but that they may not offer enough insulation to prevent the start of a house fire, even if the window doesn’t break. As he explains, there may be enough heat transmission in extreme wildfire conditions to ignite fabric materials near the window (e.g., curtains). In contrast, triple-pane glazing offers a higher level of thermal resistance that can prevent flammable materials near any glazing from igniting.

While this is certainly true, Barry and Nicely note that the risk of such an occurrence appears to be quite low (and can be mitigated by keeping flammable materials away from windows). However, the additional pane of glass can add significantly to the embodied carbon of the project and may not be entirely necessary in temperate climates where Passive House levels of performance can be achieved through the use of double-glazed windows and doors. In fact, after undertaking an analysis of the embodied carbon for a project that Barry and Nicely both worked on (Mile 17 Haus, left), the team found that the highest embodied carbon elements on the building were the photovoltaic panels, followed by the glass in the fenestration systems. This knowledge ultimately helped them balance operational and embodied carbon.

“This is what Passive House is really good at,” Barry says. “It’s about balancing the items.”

Meanwhile, Kienapfel notes that the issue is not simply about the number of panes in the glazing, but in the type of glass. His Los Angeles-based firm compared 16 different models of double- and triple-pane windows and found that criteria like acoustic performance, durability, and embodied carbon were best in double pane windows with a pane of tempered glass on the exterior and laminated glass on the interior. These units were lighter, too. Before rushing to judgment, however, Kienapfel notes that his analysis is not universal across climate zones, and that each designer should perform an independent analysis to find the right balance for them.

Where Do You Start?

Beyond looking at specific components like windows, the panel also discussed how they think systematically about balancing numerous factors, including building performance, fire resilience, and cost. For Carmel-based Nicely, he likes to start by including inexpensive components and strategies that offer good protection. For example, he prefers to minimize outside fuel loads around the house and optimize exterior assemblies for resilience rather than first considering something more expensive. As one example, he describes an elaborate sprinkler system that begins spraying down the property when it senses approaching fire. While this is most likely very effective, it's also $80,000. He finds that by keeping with passive principles, like creating strong building enclosures with simplified forms that include high-performance components, his projects can withstand extreme conditions without relying on over-engineered systems.

“Let’s just make a good building shell,” he says. “It’s not complicated. It’s not expensive. There’s nothing to be afraid of. We’re just doing a better job.”

Barry agrees that we have to let go of the assumption that high-performance buildings are necessarily more expensive to build. They do not have to be, especially if one is focused on simplifying the design.

Barry also notes that there are two additional ways to bring down the costs associated with Passive House. The first is perhaps more systematic, and it involves training more people who understand the building science that undergirds the Passive House principles. Simplified geometries perform better than complex shapes and are less expensive to build. Similarly, smoke-tight assemblies without overly intricate detailing are less expensive to build than the alternative and are far easier to build.

Barry's second point is that communication between the professionals who are designing the buildings and those who are on the job site when considering components is crucial. If the builder has experience working with a specific product and can vouch for its quality and the manufacturer’s integrity, that endorsement should not be taken lightly. Similarly, if the builder has had negative experiences with a component or manufacturer, then it may not be the best product to use, as it may translate into delays, cost overruns, and possibly even problems with performance.

Missing Links

Michler may have included a list of components that are vital to Passive House construction and fire resilience, but there are still holes that need to be filled. Michler, Ingui, and Irwin all feel that there is a scarcity of exterior shading elements in North America, which has traditionally relied on active cooling measures to keep interiors comfortable during the warmer months of the year. By contrast, Europe has a far more robust market for components that can provide passive (and external) shading.

For Kienapfel, having a combined, electrified system that can provide ventilation, heating and cooling, and domestic hot water would be ideal. These products exist in international markets, and there are some prototypes in development within the United States, but these products have yet to become common in North America.

Finally, the group agreed that zoning that addresses the changing climate of the twenty-first century is also missing from many major cities, particularly those in California. As Barry notes, many municipalities have zoning laws with a lot of “weird, sabotaging elements” that force buildings to be unnecessarily complicated. Similarly, much of California is developed largely on a suburban model, which makes it far more difficult for firefighters to defend when conditions deteriorate, as they did in Los Angeles earlier this year. There were simply too many fires happening simultaneously across too wide an area. Moreover, as each house caught fire, it hurled more embers into the air to be distributed by the winds because all the homes were effectively loaded with fuel.

Ultimately, the panelists agreed that making our cities more compact, simplifying the designs of our homes, and reducing the use of highly flammable materials in our buildings can all contribute to creating more resilient communities. If you want to check out the rest of the conference (and so much more), become a member of RB Collective!

Learn More About Passive House and Fire Resilience

Thoughtful Rebuilding After a Devastating Fire Season

Discover smart rebuilding strategies after wildfires. Learn how Passive House principles support resilient, energy-efficient homes for fire-prone regions and sustainable reconstruction.

10 Steps to Hardening Your Home Against Wildfire

Discover 10 effective steps to harden your home against wildfire. Learn essential wildfire protection tips, home safety measures, and fire-resistant building strategies for lasting peace of mind.

Family Rebuilds Stronger After Marshall Fire, With Passive Home

Discover how a family rebuilt their home stronger and more energy-efficient after the Marshall Fire by choosing Passive House design, highlighting resilience, sustainability, and modern green building solutions.