The mood at the Underground Railroad Education Center (UREC) is celebratory as of the summer of 2024. Construction is set to begin on the center’s 14,000-square-foot annex, the Underground Railroad Interpretive Center, which will significantly expand the UREC’s footprint in Albany’s Arbor Hill neighborhood, as well as its programming capabilities. Designed by Hamlin Design Group, the interpretive center will not only provide visitors with immersive experiences, access to educational resources, and a host of community-oriented events, it will also serve as a model of efficiency and graceful design.

The new center is seeking Core certification through the International Living Future Institute’s Living Building Challenge after being awarded multiple grants, including more than $1.1 million from the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) through their Building Cleaner Communities Competition (BCCC). Formerly known as the Carbon Neutral Community Economic Development (CNCED) program, BCCC supports projects that prioritize clean and resilient design and construction at the facility level.

While the performance of the building is important for meeting its sustainability goals, UREC co-founders Mary Liz Stewart and Paul Stewart have also worked to ensure that the new center fits within the fabric of the neighborhood and becomes a cornerstone to public life within the community. “It becomes a statement to the community that says, ‘This community is worth it,’” Mary Liz Stewart says. “This is going to be a building that our neighbors are going to be proud of and part of.”

The Underground Railroad Education Center

The UREC evolved out of a research project that the Stewarts began over 20 years ago. The married couple were initially interested in finding and formally marking locations around Albany that played a role in the Underground Railroad. However, they soon realized that Albany did not have the best track record with respect to historical preservation, and that many of the buildings that had been integral to the history of abolitionism and the Underground Railroad in the city had not survived into the twenty-first century. Rather than restoring or rehabilitating these buildings, they’re demolished, Mary Liz Stewart explains.

Given the city’s penchant for not preserving its older buildings, the couple decided to instead focus on period documents and the stories of individual abolitionists. The result was revelatory. “It was like opening a treasure trove,” Mary Liz Stewart says. “The voices and the stories of people who had been written out of history started emerging.”

Most of these voices were members of Albany’s Black community. Rather than being passive or supporting figures in the local abolitionist movement, they played central roles and were regularly in leadership positions. “What we were uncovering belonged to the community because we were uncovering voices of people who lived and worked and walked where we live and work and walk,” she says.

To better share their findings, the two decided to incorporate in 2003 as a nonprofit. Not long after, a fellow researcher found a flyer about an Albany Vigilance Committee meeting, which occurred at 198 Lumber Street. “Vigilance committees” were frequently organized in Northern cities prior to the Civil War to protect Black members of the community and to assist fugitive slaves as they sought their freedom. Though there was no longer a Lumber Street in Albany, the Stewarts determined that it had become Livingston Avenue after going through some old city maps and land records. Ultimately, they identified the house from the pamphlet as 194 Livingston Avenue, which was in foreclosure.

Known as the Stephen and Harriet Myers Residence (or just the Myers Residence), the house had originally been built in Greek revival style in 1847 by John Johnson, a Black boat captain. Stephen Myers and spouse Harriet Myers lived in the home during the 1850s, where it served as one of the headquarters for participants in Albany’s Underground Railroad. Stephen Myers’ activism extended beyond the abolitionist cause, as he was an active member in the New York State Suffrage Association and the American Council of Colored Laborers (the first Black union in the U.S.). According to his 1870 obituary from the Albany Evening Times, “He was a prominent man among his race, being an agent for the ‘Underground Railroad’ before the war, and did more for his people than any other colored man living, not excepting Fred Douglass.”

The ten-room residence had seen better days when the Stewarts bought it from the city for $1,500, and the nonprofit has spent over $1 million renovating and restoring the residence since its purchase in 2004. The Myers Residence now houses UREC and hosts a multitude of events and historical exhibits. It is also listed on the National Register of Historic Places, a member of the National Park Service Network to Freedom, and an accepted member of the African American Civil Rights Network.

One limitation that quickly emerged was the size of the residence. “You get 30 people in the front parlor, and you’re elbows to elbows,” Mary Liz Stewart says. As she explains, the board for the museum decided in 2008 that more space would ultimately be needed to fulfil their plans, and they searched for a potential building that they could buy for well over a decade—from approximately 2008 through 2022. During that 14-year stretch, they also purchased eight adjacent properties along the same block where the Myers Residence is located. These properties certainly had historical value, as they were also owned by abolitionists and prominent members of the Black community during the nineteenth century, but they also helped the UREC expand its programming beyond the walls of the residence, allowing for the creation of community gardens and the hosting of outdoor events.

After years of searching, it was determined in 2022 that it would be better to simply build a new facility on the properties the UREC already owned rather than purchase another building.

Building the Underground Railroad Interpretive Center

The Underground Railroad Interpretive Center will be built just to the east of the Myers Residence on Livingston Avenue. The UREC issued a request for proposal (RFP) in 2022, which attracted the interest of Owner and Managing Principal of Hamlin Design Group Shawn Hamlin, who submitted his proposal.

“I was privileged to be retained,” Hamlin says. After being awarded the project, Hamlin’s firm initiated a planning study to better understand the scope and size of the center, as well as how the space would be utilized. While the centerpiece of the building will be its exhibit hall, it will also contain a library, conference area, screening room, children’s area, giftshop, café and small commercial kitchen, supportive offices, and two apartments—one for the building’s caretaker and one for visiting scholars. To fulfill the UREC’s goals, they determined that the Interpretive Center would need to be approximately 14,000 square feet spread out across three floors—two above grade and one below.

There were additional priorities that the Stewarts wanted Hamlin to address. First and foremost, they wanted the building to be free of fossil fuel use on site and net zero. For Paul Stewart, building sustainability was a foregone conclusion. “Looking at where we are, it makes no sense to be putting up a building that doesn’t address the environmental crisis we’re facing,” he says.

Hamlin and D2D Green Design Principal Baani Singh, the sustainability consultant on the project, described several possible building standards and certifications to the Stewarts and other board members at the UREC. In the end, the team decided to pursue the International Living Futures Institute’s Living Building Challenge, largely because they felt that the main criteria for certification (known as “imperatives”) aligned with the UREC's larger mission. Mary Liz Stewart was particularly interested in certifying through ILFI because of the organization’s holistic approach to the built environment.

In terms of operational emissions, ILFI’s imperatives are less rigorous than Passive House standards, but they place specific emphasis on a myriad of factors that go into creating a healthy built environment—oftentimes in ways that extend beyond the building envelope. Buildings are required to use less carbon-intensive materials to reduce embodied carbon, adhere to sustainable or regenerative land management practices, prioritize inclusion and equity, promote biophilic design, and consider how the building fits into the surrounding social fabric.

Given the UREC’s reverence for history and place, designing a building that honored the past and met the needs of the community was crucial. Consequently, the design of the new center is not only seeking to be integrative; it is also based upon an actual historic artifact: the reclaimed timber frame of a barn that was erected in the mid-1700s in Fort Plain, a small village in New York’s Mohawk Valley.

A rendering of the Underground Railroad Interpretive Center courtesy of Hamlin Design Group.

A rendering showing the relationship of the Interpretive Center to the Myers Residence courtesy of Hamlin Design Group.

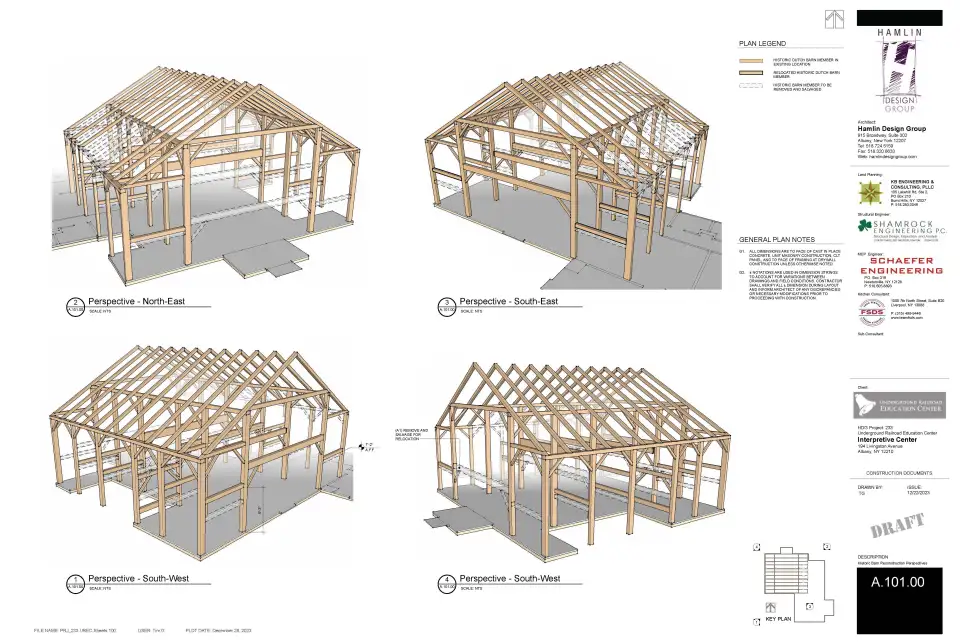

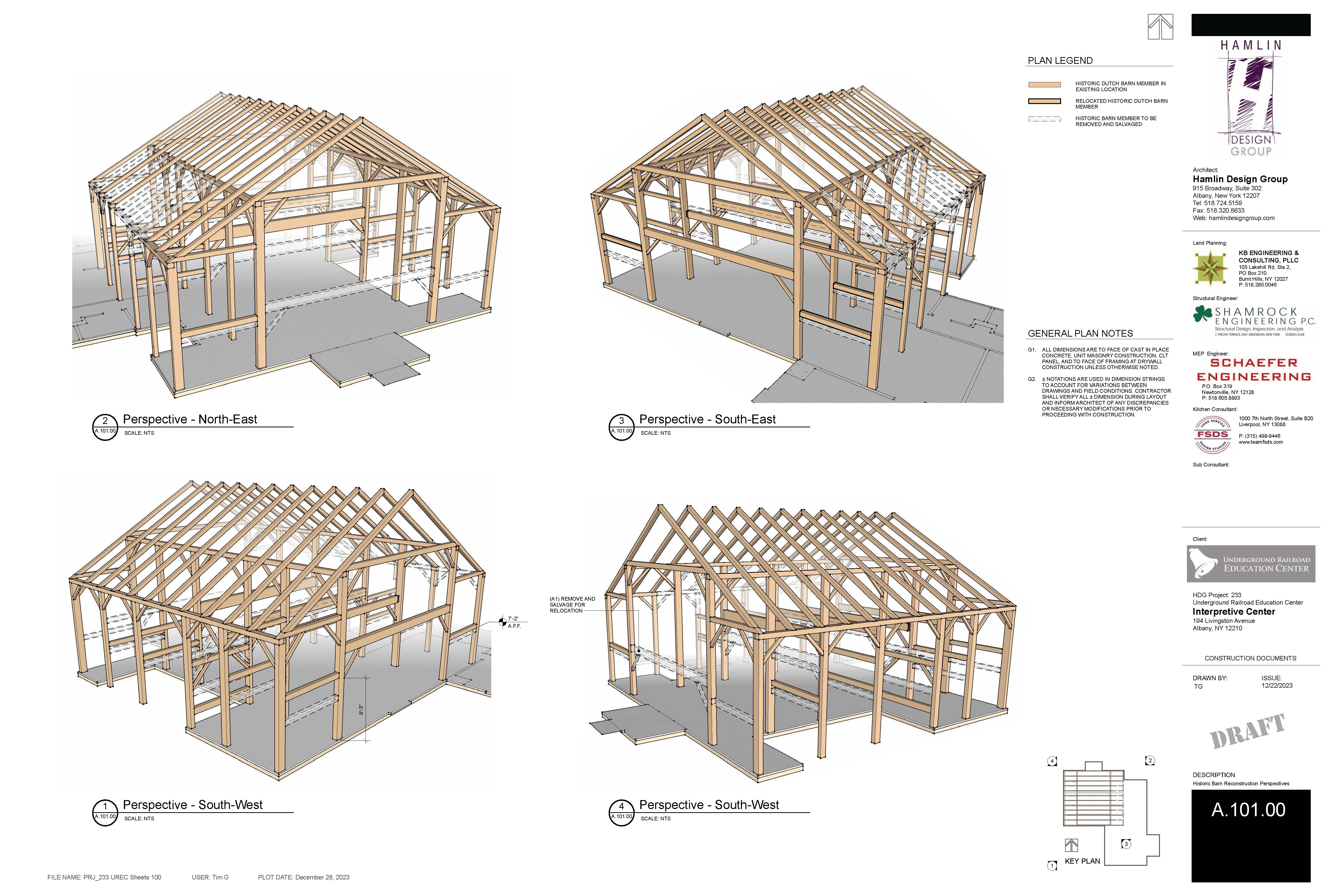

A rendering of the reclaimed timber frame courtesy of Hamlin Design Group.

As of summer 2024, the barn had been successfully deconstructed by New World Barn Company in Altamont, NY, and the 14x14 timbers and original joinery are currently being held in their facility until they can be erected on the site of the interpretive center. There, they will provide a two-story volume that frames the main assembly hall. “The presence of that timber frame allows us to very tangibly talk about enslavement in New York state and in Albany, and yet also talk about repurposing this element of history to speak about emancipation and liberty,” Mary Liz Stewart explains.

The Stewarts note that they were set on reusing the timber framing before the design process even began. Early on in their meetings, Mary Liz Stewart also told Hamlin that she was adamant about one other thing: “I don't want a box.” Elaborating on her reasoning, she explains that the UREC sees itself as a member of the neighborhood. Its buildings, both the Myers Residence and the future center, are meant to be public and to possess a sense of permeability. “I want a building designed so that when people are inside, they can still have a sense of relationship to the outside,” she says.

The Stewarts also plan to use the center as a means to provide services to the community that are currently lacking. Much of Arbor Hill is a food desert, so they plan to set up a farmer’s market on the land adjacent to the center. They also hope to provide legal clinics, job fairs, and even workshops to describe available workforce development programs or grants for local business owners.

Designing a Permeable Space

Though the social barriers between the interpretive center and the outside community will be porous, the building still needs an envelope that is robust enough to efficiently keep the building warm during the long months of an Albany winter. To accomplish this, Hamlin will use the repurposed timbers to frame the event space and exhibit hall that sits within the center of the ground floor but will create a modern shell around it using natural and high-performance materials. These materials include a stick-built curtain wall to provide transparency through the event space or exhibit hall, as well as aluminum and wood cladding elements. The latter will be thermally modified wood, which reduces the moisture in the wood, but more importantly destroys the sugars and resins that bugs and fungi use as a food source, resulting in pest- and mold-resistant cladding material without the use of chemicals.

Hamlin says that a combination of building electrification (including the commercial kitchen and two apartments), as well as high-performance enclosure assemblies and renewable energy, will keep the building fossil fuel-free on the facility level and allow for a 70% reduction in energy use when compared to a code-built building. Among other things, NYSERDA’s BCCC program has helped to fund the electrification measures.

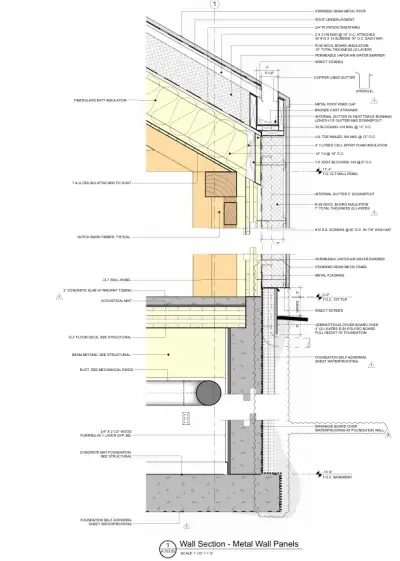

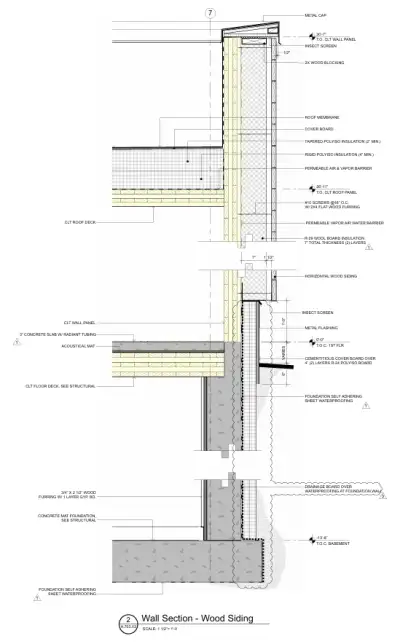

The wall assembly will include an air barrier with permeable backing that is applied directly to cross-laminated timber (CLT) panels, as well as a 7-inch layer of Rockwool insulation, to achieve an R-value in the high 30s. The CLT panels will be exposed internally and provide an appropriate aesthetic backdrop to the reclaimed timber elements. The gabled roof will consist of aluminum C panels manufactured by ATAS International below which will be a similar assembly as the walls—continuous Rockwool insulation, an air/vapor barrier, and CLT paneling that is exposed on the interior—though the insulation layer will be 10 inches thick and achieve an R-value of 38. Meanwhile, the flat portion of the roof will be modified membrane. The team has decided to use aluminum-clad, double-pane windows from Pella.

With respect to renewable energy, the center will use a combination of solar panels and a geothermal heat pump (GHP) ground loop system. The former will be a 120-panel system installed on the flat portion of the roof that will generate an estimated 29MWh per year. The latter is being installed by Aztech Geothermal and will rely on ten, 450-foot-deep wells situated around the property. The piping from these wells will be fed into the GHP system in the basement that then transfers energy to the radiant in-floor heating in the event space and exhibit hall, as well as heat pumps situated throughout the building.

The marriage of efficiency, preservation, and resiliency may be central from the perspective of an engineer or an energy consultant, but to most visitors they will be secondary to some of the more biophilic flourishes within the building. These include a lighting motif in the event space and exhibit hall framed by the repurposed timbers that mimics fireflies and a ceiling feature in the adjacent space that appears to be rolling clouds. The latter impression is created by the clever use of sound batts made from a fabric that’s been given a Class A fire rating.

Hamlin notes that the high-performance design elements and architectural embellishments may be the result of hours of work at the literal drawing board, but the ability to turn these ideas into something tangible is only actualized by engaged and willing clients. “We need to have clients who also have dreams and ideas that we can facilitate,” Hamlin says. “It has been a tremendous privilege to work on a project like this that has such high aspirations.”

Project Team

Architect: Hamlin Design Group

General Contractor: Bast Hatfield Construction

Structural Engineer: Shamrock Engineering, P.C.

Civil Engineer: KB Engineering & Consulting

Sustainability Consultant: D2D Green Design

Landscape Architect: Land Art Studios

Geothermal Consultant: Aztech Geothermal

Designing the Interpretive Center’s Water Detention System

Similar to other older cities in the Northeast, Albany’s combined sewer and storm system is on the older side and lacks the capacity to handle major surges caused by strong rainstorms. Unfortunately, when it exceeds capacity during a large enough storm, the excess ends up in the Hudson River. To mitigate the pollution of the river, the city created an overlay district for areas that connect to the combined sewer and storm system, which includes Arbor Hill, and now requires new developments within the district to reduce stormwater flows into the system through flood stormwater management systems.

According to Hamlin, the water detention system for the center, known as a water gallery, will be indiscernible to the observer and spread out beneath the property. In the event of a storm, the gallery will be fed by a series of culvert pipes that sit beneath fabric, crushed stone, and soil. The fabric, stone, and soil filter the water. In the event of a major storm, the filtered rainwater will be directed into the gallery, and then gradually released back into the soil.

“We're able to handle up to a hundred-year storm—all on this site,” Hamlin says.

Read About Other BCCC Recipients

Passive Sugar Shack to Achieve Net-Zero Carbon Emissions

Discover how a passive sugar shack is designed to achieve net zero carbon emissions by integrating energy-efficient building techniques, sustainable materials, and innovative green technology solutions.

Net-Zero Retrofit to Rise in Troy

Discover how Troy is embracing sustainable building with a net-zero retrofit project that improves energy efficiency, lowers carbon footprints, and promotes eco-friendly living for future-ready communities.

NYU to Retrofit Historic Rubin Hall

Discover how NYU plans to retrofit historic Rubin Hall to meet modern Passive House standards, prioritizing sustainability, energy efficiency, and greener campus living in New York City.