It’s common to assume that high-performance building and affordability are a tricky scale to balance. But Auburn University’s Rural Studio has spent the last three decades working with architecture students to design and construct homes and community projects in West Alabama built to the highest levels of durability and efficiency while maintaining affordability. On October 19 Emily McGlohn and Betsey Ferrell Garcia of Rural Studio will join our video crew to talk through the studio’s process of client-specific design, increasing performance, and prototyping for increased impact across the Southeast. Emily is an associate professor at the Auburn University School of Architecture. During the last three years, Emily and her students have built three homes for local community members, and they will begin another one soon. Betsey, assistant research professor at Auburn University, has experience in high-performance arts, higher education, and K-12 facilities that inform her work envisioning and designing efficient, resilient, and equitable housing for communities that need it most. As a research professor, Garcia leverages Rural Studio’s long history of collaborating with West Alabama to address housing needs throughout the Southeast and beyond. This presentation is filled with tangible lessons learned (they even wrote a book on it) about performance-driven affordable housing in Western Alabama. Join us to hear from Emily and Betsey about the design process, research initiatives, and impact coming out of Rural Studio’s impact building client-specific Passive House over the last three years.

Check out the full transcript:

Emily McGlohn:

So, all right. Hey, good evening, everybody. Thanks for having us. Betsy and I are happy to share Rural Studio's and Front Porch Initiative's work with you. I'll begin with an explanation. Yep. There we go. I'll begin with an explanation of who we are and give you a description of what it's like to be a student here at Rural Studio. Betsy's going to go over our collaboration, Rural Studio's collaboration with Front Porch Initiative, and talk about the lessons that they're learning from monitoring the performance of the houses that their group has built.

Emily McGlohn:

Rural Studio is a design-build program, which is part of the architecture program at Auburn University. We're a fully immersive program and based in rural West Alabama. So think of us like a study abroad program in our home state. Next slide. Yeah. So we're fiercely placed-based. That's our number one characteristic. Auburn's main campus is located about three hours east of us. And so our students move out to Hale County to participate. Our main office is in Newbern, which is a little town of about 300 people. And our service area rests within a 25-mile radius of that home base.

Emily McGlohn:

Rural Studio started over 27 years ago by building unique homes for single families. Initially, the design process really didn't focus on replicability or affordability and the materials that we used like old sidewalk pieces and that's what you're seeing in that little building in the foreground there. Our carpet tiles or hay had little value until we assigned them a value. And we were probably using those inexpensive materials because we couldn't afford much else in the beginning when we were first started.

Emily McGlohn:

So in addition to housing, our students also designed and build projects for community organizations. The Newbern library like the image that you're looking at there is an example of giving a new life to a cornerstone building in a small community. It focuses on education and this state library also offers the only high speed internet in the area. Lions Park is a multiyear project, over 10 years of projects in this particular park offers outdoor recreation opportunities to community members in which promotes health in the area.

Emily McGlohn:

We look for organizations already doing great things in our area to support like the Boys & Girls Club here of Greensboro. We've actually built three Boys & Girls Clubs in our 27 years and programs like these provide invaluable afterschool programs for the kids in our town. But we're a housing and food first organization. It's the way we think of ourselves. Our student-built greenhouse in this image and working vegetable farm help us understand the challenges of accessing fresh food in rural areas. And we all share in the responsibility of growing food.

Emily McGlohn:

The students work on our farm early in the morning. So we build together and we eat together. At that greenhouse, I won't get into it too much, but it's a passive greenhouse. Those barrels are filled with water and act as a thermal mass to help keep the little plants warm in the wintertime. Well, we believe that proper food in and housing are the bedrocks to a sustainable community. These basic necessities lie at the heart of Rural Studio's mission.

Emily McGlohn:

For almost 30 years in West Alabama, we've discovered community sustainability kind of like a web. So for example, when residents weren't able to get homeowners insurance in their community because there wasn't a local volunteer fire department, they started a volunteer fire station on their own. They applied for a grant and won it and were able to purchase this brand new fire station, but they didn't have a place to put the fire truck. So Rural Studio worked with the town to build this new firehouse and town hall. The fire station makes homeowners insurance possible, which makes financing possible, which makes building a house that's titled as real property possible. So it's like a web.

Emily McGlohn:

And then this of course leads me back to housing, which is the focus of this presentation, the high performance housing that we design and build in West Alabama and now in the region. So Hale County lies in one of the most impoverished areas in our country. We are in Hale County, but Perry County is right next door and Marengo County, those are our three main counties. And folks that live here are living at or below the national line of poverty over 25% in our particular county. And before the house trailer, which is really common now, small, well-used homes like this. I call this a well-used home are common site. And you can still see stick built older homes like this, but the truth is these days it's much easier to get a note like a car note for a used or new trailer such as this.

Emily McGlohn:

And the problem with this of home is that it depreciates in value. They're not particularly efficient as you probably know and they have about a 15-year life expectancy, even though you typically get a 30-year note to purchase one. So most of our clients own their property, but they don't really have the means to build a house on it. And it's actually kind of hard to find someone to build a house around here. So the most affordable option is in fact not affordable at all. And this reality has helped us shift our efforts from individual solutions like the Haybale House that you saw in the beginning of the presentation for individual families to prototype research and development.

Emily McGlohn:

And this is an example of one of those houses, Joanne's House. The 20K House is an ongoing research project to develop well-designed, affordable houses that support an industry of home building across the rural south. The project seeks to create dignified houses that make responsible home ownership a possibility for everybody. The academic and research programs at Rural Studio create a loop between thinking and practice. On the academic side where I work, students develop new prototypes and refine existing ones.

Emily McGlohn:

These designs are studied and further refined by the team at the Front Porch Initiative where Betsy and Mackenzie work. But before Betsy explains that work, I'm going to describe the principles behind the 20K House and some examples of student designed homes. In 17 years, over 25 different prototypes of 20K Houses have been built. Typically they're designed without a client in mind or without a site. They will be built for a client, but because they are prototype, the designing without a client in mind or without a particular site allows the students to concentrate on a specific design programs for that particular project.

Emily McGlohn:

But however different, each of those houses, each of those prototypes share nine core qualities. The essential criteria, which we think all buildings should really have are durability, buildability, water resistance and security. These characteristics are now nothing new, but in addition to the core criteria, 20K Houses also possess or have presence and dignity, they foster a sense of community, which is usually expressed through Front Porch. They promote health and wellness with access to daylight, fresh air, and we use healthy materials and they provide comfort to the homeowner.

Emily McGlohn:

And 20K Houses are accommodating to age and accessibility, and they also all should possess a sense of craft. We are an architecture school. Our number one goal is to teach architecture students how to make better buildings. And so just because it doesn't cost a lot of money doesn't mean it can't be beautiful. And so they're also crafted well. And students' collaboration is key at Rural Studio. We start by drawing on the same piece of paper. This is my class a few years ago. We have a day long charette where every 45 seconds a new idea is represented on a piece of paper, and then it's pinned on a wall where we're able to start collecting ideas and seeing where our similarities overlap.

Emily McGlohn:

The house designs aren't predetermined and we never vote and I don't pick what they build. We all work including me to gain consensus by sharing ideas and finding similarities and contributing to the group. We all have to agree on what to build. It's very important. It's not an easy process. It's pretty painful, but we do it. And then I start each semester with what I call a Sawhorse Race students design to build a set of sawhorses with a set list of materials. They build one set, we test them and then we usually we fix them and sometimes we have to disassemble them or scrap them because they don't work.

Emily McGlohn:

But this early assignment familiarizes them with the building materials that we'll be using for the house and also they begin to make associations with performance testing to understand that everything they make and build serves a purpose and should be tested. And we get to use the sawhorses during construction, of course. And in my studio particularly, we build a house for a community member each year, and it's paid through by grants and donations. So it's a gift to the homeowner for having to deal with us for over a year.

Emily McGlohn:

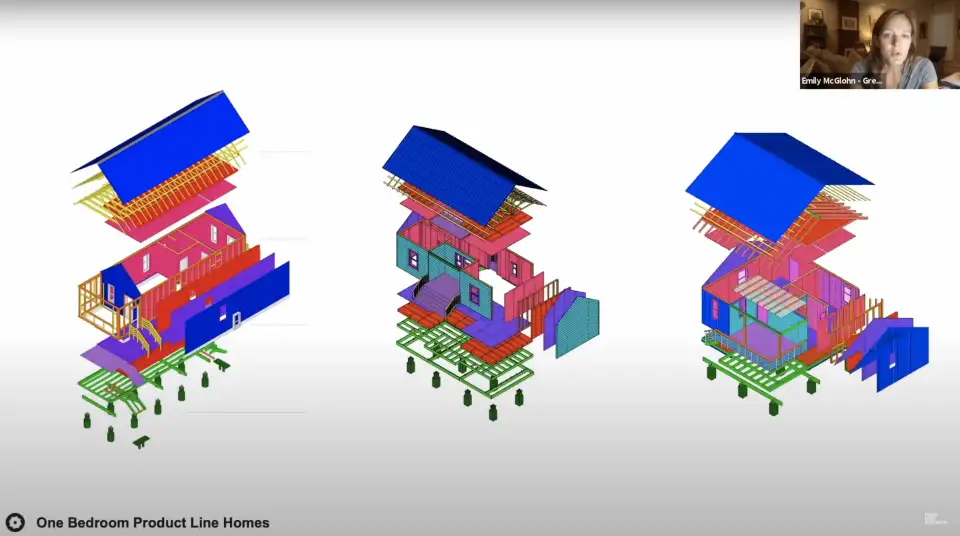

But when we aren't designing a new prototype, we work to refine the ones that we already have in our portfolio. For the younger students who I teach, we study one bedroom prototypes and we call these the Product Line Homes, and we pick one to build for the client and for the property. So the design is in understanding the client and the property, and also different building assemblies. That's the design project for the younger students. And we learn about every aspect of the home. These are sketch up models where students turned two-dimensional construction documents into piece by piece sketch up models to understand the buildability of these houses.

Emily McGlohn:

And they're really good examples of stick frame construction and basic advanced enclosures. This is pretty basic stuff, but we try to do things the right way in an affordable manner. The first goal of finding a prototype is testing new assembly ideas. In this study that's on your screen, we looked at how using a slab on grade foundation, which has many benefits over a pier foundation would affect the architecture. It might perform better, but it might change the architecture and we need to understand these things.

Emily McGlohn:

So we study alternative foundations, wall assemblies, porch configurations, cladding options, lots of variations that my students study. And we draw a lot at Rural Studio. We draw a lot by hand. These full scale sections that I had students draw help them to understand the magnitude of the project scale of the home and the details of construction. It was probably the biggest architectural pin-up in history, but we have fun doing it. It's one of the most important parts of our work and drawing at full scale is really helpful to understanding how a building goes together. And we also study existing buildings. We study what works and what doesn't. We go back and visit what we've built and we try to understand what didn't work.

Emily McGlohn:

Let's see. Real buildings and real clients are really the most two important aspects of Rural Studio. Working with the client is an invaluable opportunity for an architecture student. The second goal of refining the prototype is to allow the client to push back on the prototype. So what I mean is that students learn about the life of their client and make changes or alter the prototype to suit them. And what we hope is that because these prototypes were designed in a vacuum essentially without a client, this is a way for the client to influence the prototype in small ways. And this process usually begins with very, very careful renderings of the existing home. I call these empathetic drawings and through these very careful studies and time-consuming renderings, we begin to understand and love what's important to our client.

Emily McGlohn:

So for example, this is my client, her name is Ree. This was her original trailer home. She lived in it for 42 years, which is a long time for someone to take care of a trailer home. So Ree's truck is rendered in this drawing and the proximity of it to the front door is what's important. We learned that Ree has knee troubles and was parking as close as she could to her front door because it was easier for her. So this translated into a fully accessible entrance to the new house, which helped us understand how to incorporate a ramp into one of the Product Line Homes.

Emily McGlohn:

So students illustrate their ideas in lots of ways and present them to classmates and to the client when it's appropriate. We have an incredible lineup of consultants that help us with all our projects, code consultants, engineers, architects, landscape architects and others visit us for reviews. And our students do very real drawings also. No hammer is swung on a site without a set of drawings. Scheduling is also handled as a group with a modified full planning session. I divide students into expertise teams that represent construction trades and we schedule out the project, but the real work happens on the site.

Emily McGlohn:

The very real drawing turns into very real building like this elevated slab detail. Remember Ree's truck and needing to provide her an accessible house. Well, by selecting an elevated slab, which is nothing new, it was just new to Rural Studio. By exploring this foundation, we were able to lower her house to about 16 inches above grade instead of about a pier on beam. A pier and beam is about 36 inches above ground. So that means that we could get a very reasonable length ramp under cover and get her to her front door faster.

Emily McGlohn:

We usually build with lumber and wood because in our area it's a renewable resource, it's local and it's forgiving for our students. And it's probably the most basic construction system, which is a good foundation for young architects to learn to work with. So Ree still parks as closely as she can, but now she has a ramp and a handrail to help her get into her house. And you can see that Ree's house is a version of Joanne's Home, which is one of those Product Line Houses. The hill trust makes it a little taller. Next slide. Yep. Yep. There we go. The hill trust makes it a little bit taller and the porch is a little bit shallower so we could move the washer and dryer into the bathroom.

Emily McGlohn:

But it's always a game of inches when modifying these pretty small houses. The latest house we just finished is one for Ophelia. Ophelia has lived in Newbern for more than 50 years. And through drawing Ophelia's home, we learned some important things about her life. Connectivity, which all of these satellite dishes and the history of connecting to the outside world is drawn right here in this rendering. But it's important to her. We also learned that Ophelia likes to sleep in her living room and there are several really good reasons for this. She likes to sleep with the TV on so she doesn't get lonely. And it means that one bedroom is open for her son. After her husband's passing a few years ago, her son comes to stay with her sometimes, and she wants him to have a place to stay.

Emily McGlohn:

And we didn't know this when we selected Ophelia, we probably would've still worked with her, but I can only build one bedroom homes because of time and budget constraints, but we still wanted to accommodate this really important family unit. So what did was design what we call a quarter bedroom into Ophelia's house. The students study not only the outside of the house, but we look at all of the client's belongings and what they'll be bringing over to the new house so we make the right selection. Site constraints are always important. Ophelia lived on a third of an acre and turned out we could only build her house on a third of that third of an acre because of power lines and septic and driveway. So these are all really very real things for young students to grapple with.

Emily McGlohn:

And in the end, another version of Joanne's Home was the best fit for Ophelia. And you can see how the original house has been modified to include what we call the quarter bedroom. It's a small nook in the living room with its own storage. Ophelia puts her daybed in there. And the bedroom is reserved for guests. For other clients, this space could be a home office, extra storage, or where a grandchild could sleep for an extended stay if necessary. Ophelia is very happy with her nook. She's moved into her house and she calls it her bedroom and the other one her other bedroom. So they're both her bedrooms, but she has two sleeping spaces. And we also provided an accessible entrance for Ophelia of course.

Emily McGlohn:

ut building iteratively is a luxury in an academic setting. So studying and comparing is a great way to learn about works best and Betsy and her team take this concept even further. So I'm happy to be the teacher of the next generation of designers, builders, and architects. And we hope that the style of education will encourage them to be citizen architects throughout their career.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

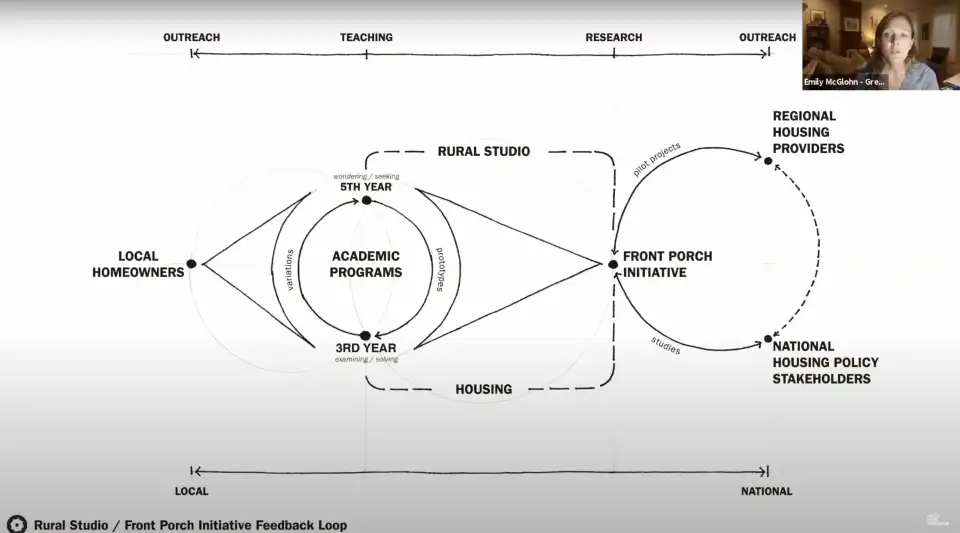

As Emily mentioned, our students out in West Alabama have designed over 25 prototypes in 17 years of study and research. And our team began to consider how we could extend the impact of this research in housing access and affordability beyond West Alabama. So we developed Rural Studio's Housing Affordability Technical Assistance Program that we call the Front Porch Initiative. It's a faculty-led initiative where we offer housing products and technical assistance to housing providers working to deliver homes in their own often under-resourced communities.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

In our service area of West Alabama, Rural Studio works in a sort of mutual aid model where students design, build and provide houses to local residents who wouldn't be able to afford a home under normal circumstances. And in turn these owners act as clients, as Emily described, playing a pivotal role in our student's architectural education. The Front Porch team takes the knowledge and products developed over the years in West Alabama, and offers it to housing provider partners outside our service area through their established delivery method with contractors and [inaudible 00:21:08] volunteers. These partners are able to offer the same energy-efficient, resilient, and healthy homes to their clients.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

We view this collaboration between the two teams as a symbiotic relationship of information sharing. As Emily described, the students work to develop products and tailor them to a specific client. And at the same time, the Front Porch team works with housing policy stakeholders and a network of regional housing providers to advance equitable access to affordable housing. We then share the information learned creating a constant feedback loop, serving both groups. Each refines the others' efforts yielding the better products and technical assistance.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

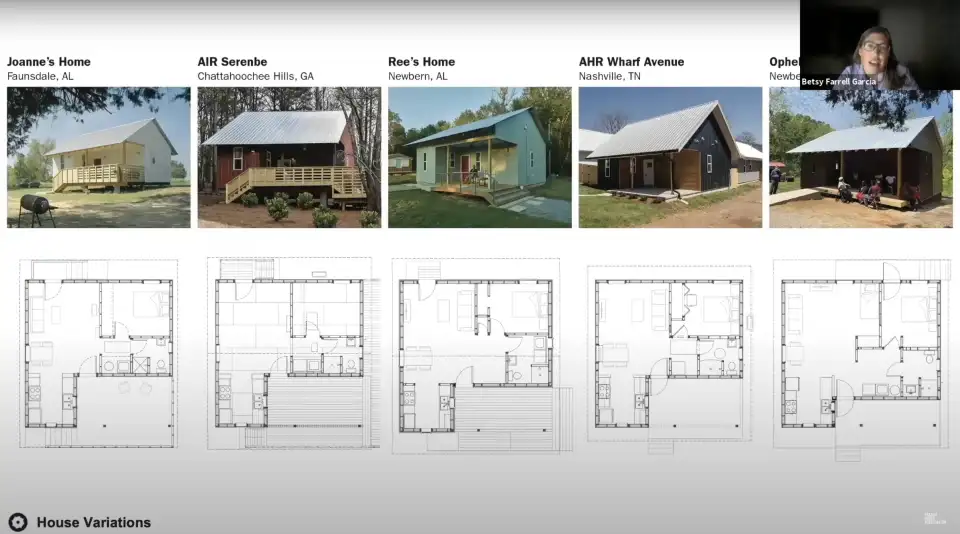

The Front Porch Initiative takes one and two bedroom prototypes designed by student teams at Rural Studio and develops them into a product line of homes. Of the many prototypes developed at Rural Studio, we currently have five Product Line Homes, each named for the first homeowner of that home. They are one and two bedroom home that are small, but not tiny. They are designed to be as efficient and durable as possible, meet all conventional code and lending requirement, be titled as real property and be lived in normally.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

Here we have Dave's House, Joanne's, MacArthur's, Buster's and Sylvia's House. Through the Front Porch Initiative Technical Assistance Program, we share with our builder partners our knowledge on what to build relative to codes, universal design lending and insurance requirements and how they work together. And we synthesize this information tailored to the specific needs of a partner in a set of construction documents and specs that show not only how to build, but more importantly, relative to high performance standards, why to build that way. And over the years, our team has developed an instruction manual that helps our students and partners understand the hows and whys of high performance home building.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

Of note is the iterative nature of our process. Here are five versions of the prototype built in Alabama, Georgia, and Tennessee illustrating the inherent flexibility of these products. They can meet a wide range that can be adapted to meet a wide range of sites, climactic conditions, and performance objectives as needed for each client's particular circumstances. And as part of our technical assistance program, we've developed a library of materials illustrating the range of variations possible. We understand how to design to a high standard of building performance and the impact different assemblies can have on that performance.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

Ultimately, we aim to study the relationship between high performance building and affordability, and how one can affect the other. Affordable housing often focuses on lowering the initial construction cost to the detriment of building performance. We seek to find the balance point between the upfront cost of improved performance and the backend performance benefits or consequences. By investing in improved efficiency and durability in a healthier home and in the surrounding community can we lower the homeowner's energy bill on insurance premiums and reduce chronic illness.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

We're currently working with a network of housing providers across the Southeast in climate zones two, three and four. The Front Porch Initiative provides the information, knowledge and know-how to help our partners make informed decisions regarding both the quantitative and qualitative aspects of building performance, so that they can provide high performance homes to their clients. Each house we build offers the opportunity to study different issues of efficiency, resilience, wellness, and community building. And I'll share briefly what this looks like on the ground starting with one of our first projects outside West Alabama.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

A case study of two versions of the Product Line Homes. With this, we'll explore the pluses and minuses of different building standards in their delivery and talk about out the intersection of energy efficiency and resilience. Auburn Opelika Habitat for Humanity is our local habitat affiliate with which we have a long history. These two houses were constructed via design-build studios in a partnership between architecture and building science students who provided project research, design development, and volunteer construction labor as part of their coursework with a professional contractor acting as the project manager. These were both versions of the same two bedroom, one bath house built to different performance standards.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

In this aerial view, you can see the confluence of two street grids and the irregular parcels that result. The orange outlines show property lines for these two parcels that had remained unutilized in the affiliate's portfolio for years. The affiliate was unable to utilize these parcels because their traditional three and four bedroom homes wouldn't fit on these irregular sites. The introduction of a smaller two bedroom home, not only unlocked these and other parcels for the affiliate. Building homes on these parcels increases property value and adds to the local tax base. The smaller protocol type also expands the housing providers client base.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

In addition to their energy and resilience performance, we believe that these homes strengthen their community, a less tangible measure of home performance. This site plan shows how the houses fit on their sites within the tight project setbacks, House 66 of the top of the screen was built in 2018, and House 68 at the bottom of the screen in 2019. While each house was built to the FORTIFIED Gold high wind resiliency standard, they were each built to a different energy efficiency standard.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

Quite often, we talk about the added cost of increased performance. These studios took the opposite approach. They built to the highest standard then applied the PHIUS objectives like rigorous air ceiling to the zero energy-ready home in an effort to maintain a high level of performance while reducing costs. Developing a comprehensive understanding of the more prescriptive PHIUS standard was invaluable to us as we later built to a more descriptive zero energy-ready standard. Under our direction, the students in these two design-build studios took the prototype designed by Rural Studio students and adapted the assemblies to meet the respect the building standards.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

And based on the experience of building the first home, the second studio analyzed to assemblies, components, detailing and construction processes. And we identified five key areas where we thought we could reduce construction costs in the second home. Once the homes are complete, we installed circuit level monitoring equipment and we're tracking energy use to compare the performance of each home.

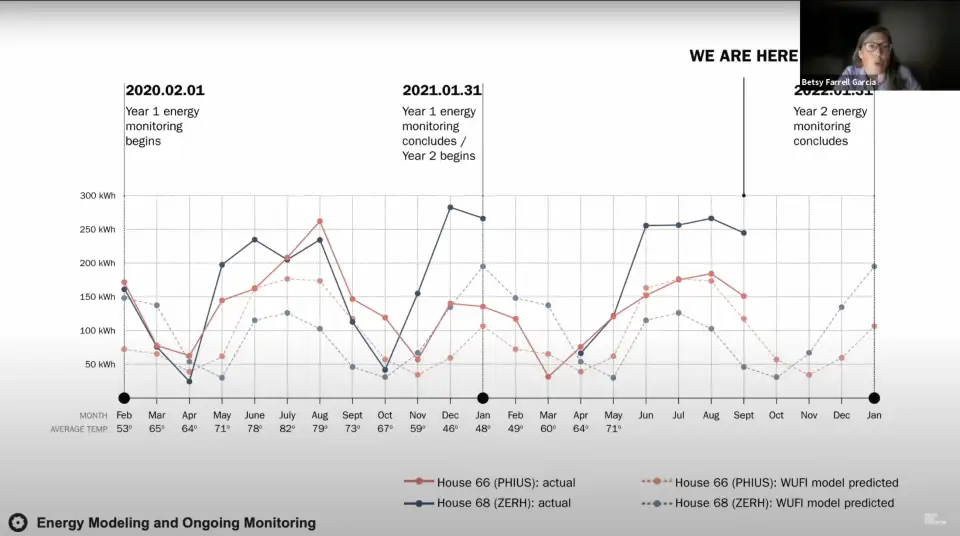

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

Every month we download power consumption data and measure it against the model data. This graph tracks the energy required to heat, cool, ventilate and dehumidify both houses. As an example of how we utilized this fine-grained data collection, last summer, we noticed excessive power draw for a circuit at House 68. Turned out that the faulty humidistat had that dehumidifier running continuously for the months of May and June. Had we not been tracking detailed circuit level energy usage, we likely never would've caught it and known to repair it.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

So this tool empowers the homeowner, not only to use their house more efficiently and lower energy use, but also know when their systems are operating appropriately. Now collected one full year of comparative data from both houses, we've moved into a second year of data collection. Spikes in energy use can be attributed to that faulty humidistat which broke after we fixed it and to the stay-at-home order for the pandemic. We do have a gap in data for House 68 due to a power outage sending the monitoring system offline. So we use this data to explore a number of research questions. We're comparing construction costs between the two houses and evaluating how differences in construction affect operating costs for the homeowners.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

We're continuing our research on how actual energy consumption differs from predicted use and how heat transfers through key locations in the assemblies. And based on our preliminary findings, a zero energy-ready home is performing comparably to the PHIUS home. Taking over the life of the mortgage, the higher cost of construction does not bear out incomparable energy savings. And this comparable energy performance is in large part due to the construction means and methods that we learn about building the PHIUS home and now apply to all our homes regardless of the standards to which we build.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

The experience of building and monitoring these houses has also helped us shape our process with other partners. Our process involves extensive energy modeling during design to optimize assemblies and details, and to ensure each design meets or exceeds its energy standard. In the Opelika homes, we modeled both homes in WUFI since it was required for the PHIUS process. And since it provided a more detailed view of energy consumption categories. Since the volume of our homes are small relative to their exterior surface area, we used a beta version of WUFI that took this into account.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

And with subsequent partners, we model each iteration in Ekotrope So we don't have quite the same level of relative to the categories, particularly HVAC energy consumption. But it does allow us to size equipment properly and estimate a HERS Index. Second, as building construction progressed, we tested the project's performance to confirm that it was meeting the air tightness goals of the energy modeling. We performed a blower door test at the three stages when the framing sheathing windows and doors were in after insulating and completion of construction. This allowed us to course correct after each stage of construction.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

We also found the blower door test to be a powerful teaching tool, a tangible method for demonstrating building science principles to students and as we'll discuss later, contractors. Third, for each home, we sought verification of performance through third-party certification. These certifications can help housing providers prove to project sponsors that performance criteria have been met. They can provide documentation to homeowners for incentives like tax credits, and they can equip appraisers with tools to appropriately of value the home.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

However, for housing providers unfamiliar with Beyond Code certification, it's key to communicate the sequencing of field verification through the development and construction process. In fact, a miscommunication that required field verification costs us our chance to achieve zero energy-ready certification at House 68. Once the homes are occupied, we monitor energy use remotely and we track actual energy performance compared to consumption predicted by the energy models. Knowledge we've gained from this iterate process informs our ongoing work and helps our housing partners make better informed decisions about the Beyond Code standards they may pursue as well as the construction processes necessary to maximize these standards.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

So now I'll share a few of our lessons learned with the field test partners through this process. We previously showed a graph comparing House 66 and House 68 energy consumptions in contrast to these graphs show modeled versus actual for the first house. The goal of energy efficiency measures is of course to reduce overall consumption, but it also helps smooth out the variability of energy use month to month by reducing the peaks in the hottest and coldest months of the year. This helps our homeowners have more predictable energy bills. You can see from this graph that our modeled energy uses a bit flatter than our actual energy use so we know we still have some work to do there.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

WUFI provides predicted estimates for seven of areas energy use. To simplify, we've grouped these into three categories. Our first category at the top includes energy required to heat, cool, ventilate and dehumidify the home and this usage is largely occupant-driven. We are encouraged that our actual consumption is tracking relatively close to the predicted use. By comparison, our plug loads very widely from the model predictions. Since these are occupant-driven, this observation suggests an opportunity to share this data with the homeowner may help them make better informed decisions about energy usage.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

It also calls into question whether the modeled assumptions are accurate and whether we should adjust them moving forward. Nashville, we've completed four, one bedroom homes in partnership with an affordable housing provider who utilized a for profit contractor to construct the project. And we provided technical assistance to the contractor throughout construction on all aspects of home performance. These homes utilized a detached duplex zoning, which allowed us to build four homes with four separate real property homeowners on just two small narrow lots. And the homes are arranged in such a way as to provide front yards, off street parking and a shared common courtyard space seen here.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

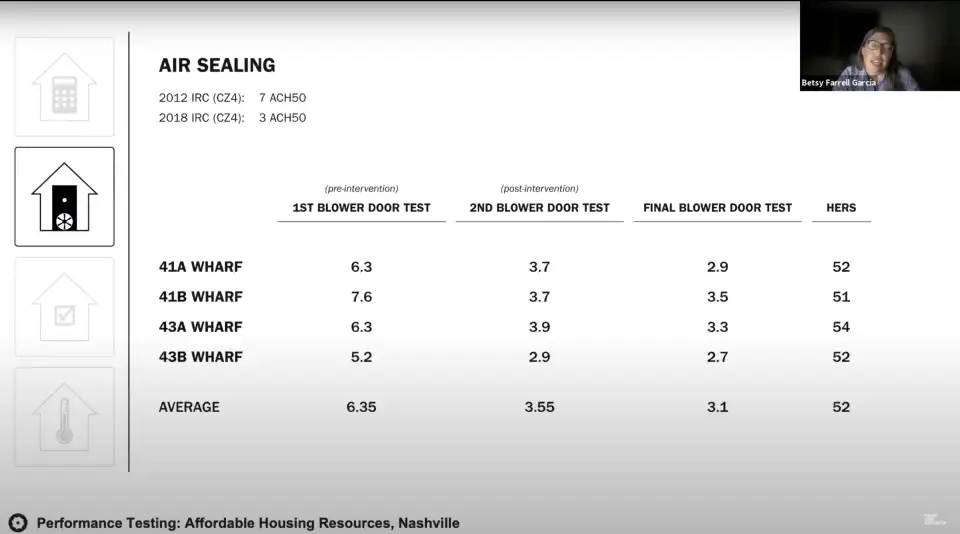

These homes aren't built to any UpCodes standards. In fact, the adopted code at permitting was 2012 IRC, but with 2009 IECC are values and area filtration numbers 7 ACH 50 for climate zone four. Because Nashville was preparing to adopt 2018 IRC and IECC, the contractor was interested in trying to meet our modeled goal of 3 ACH 50, which is the 2018 requirement for climate zone four. So it's part of our technical assistance. We pursue a HERS certificate on all our houses and based on our experience with the Opelika houses, we conduct a blower door test with all our partners at the HERS Raters [inaudible 00:34:16] board inspection, although it's not required for certification utilize this initial blower test in the Nashville project to not only test the performance, but rather as a tool to help the contractor quantitatively understand the impact of doing things right.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

And to communicate with the subcontractors early in the construction process of what doing things right really means by engaging the contractor directly with the energy consultant and HERS rater. And evaluating building performance at several pre- moments during construction, we were almost able to meet 2018 energy code expectations while utilizing 2012 energy code requirements for construction. This was an important learning opportunity for everyone involved as the impact of doing things right or otherwise focusing on construction means and methods and not just on the utilization of advanced materials and assemblies is key to increasing building performance without increasing construction costs.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

Moving down to the Florida Panhandle, we're continuing this type of technical assistance and learning and we have the first of two of four [inaudible 00:35:16] houses under construction with a local habitat affiliate who was particularly drawn to our houses due and narrow lots and slope of the parcel. Their standard three bedroom house was unable to navigate the sloping site, but these houses are inherently flexible and can accommodate a range of sites and climate zones. We're in the process of building two, two bedroom and two, one bedroom homes. This project is also important as we've been able to add a small local college's new construction workforce development program to address the much needed workforce piece of the housing affordability puzzle.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

This project works to respond to a number of different challenges that we find in many areas and it illustrates the multidimensional response to housing inability in much like the Opelika houses, these are being built to multiple Beyond Code standards. They're located in a rural area and many of their certifying agents are driving at least an hour to get to the project site. The nearest ENERGY STAR certified HVAC installer was an hour away and they quoted the affiliate a price 50% higher than their local HVAC installer had quoted for an equivalent system.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

This was going to be cost-prohibitive for the affiliate, but our ENERGY STAR consultant pointed out that since we're using a package ductless mini split system in the house, we were exempt from the need for a certified installer. In this instance, mechanical system selection will facilitate the housing provider's ability to achieve verification of the home's performance. At a minimum, this will unlock funding for the habitat affiliate. It also has the potential to boost the home's appraised value and possibly provide a tax credit for the homeowner.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

And since we're talking about HVAC systems in these houses, here's a quick view of something we've learned as something we're studying as a direct result of the post-occupancy monitoring in Opelika. We used eight ERVs to supply fresh air to the bedrooms and exhaust stale air from the living area and bathroom in those two houses. However, we've realized that this created positive pressure in the bedrooms and readings showed elevated temperature and humidity levels in these spaces. Because the conditioning system was located in the living rooms, positive pressure prevented the tempered air from migrating into the bedrooms. So moving forward, we've revised the ERV duct layout so that the fresh air supplied into the living room and the stale air is exhausted from the bedrooms.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

This creates negative pressure in the bedrooms, which we predict will help pull the conditioned air through the house and into these spaces. And we will learn soon when we install our monitoring equipment in Nashville. Lastly, we've learned that a bit of planning early on can simplify energy monitoring in the post-occupancy phase. Most HVAC equipment and large appliances are already on dedicated circuits, but by asking the electrician to separate different systems like separating lighting and receptacles on the different circuits, the data connected can be more useful with minimal added cost. And that's one of the biggest takeaways for this work. Means and methods can have large impacts, either positive or negative at minimal cost. Do sweat the small stuff.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

This collaboration between the Rural Studio academic programs and the Front Porch Initiative has formalized a process that enhances our work work. It makes the student work more intentional because they know their efforts feedback into the larger research initiative. Through this shared process, we aim to understand how the work can be more broadly meaningful and impactful at both local and regional scale.

Betsy Farrell Garcia:

Thanks so much for your time tonight. We look forward to your questions and please feel free to reach out to us if anyone has questions or any more details about our work. And if you ever find yourself in Lower Alabama, swing by and come visit.